Will India replace China as the driving force in the Global Economy?

By Ángel Martín Oro April 14, 2016

Translated from Spanish by Robert Goss

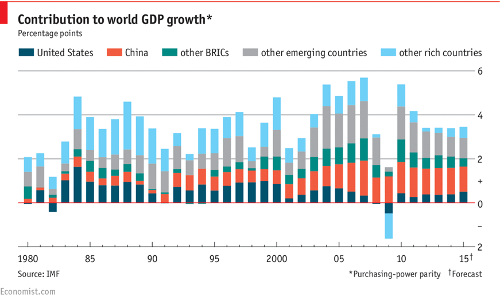

The booming increase in China’s economy in recent decades, and now the current downswing, has seen and is currently experiencing very important consequences. This comes as no surprise given the size of its economy. Its contribution to the growth of the global economy in general, and to the demand in commodities, particularly in the last decade and a half, has been quite substantial.

Since 2005, China’s economy has consistently accounted for more than one percent of the global economy, having reached a max in the year 2007 at 1.6 percent when its GDP raised 14%. Despite its slow down since 2007, it is estimated that this contribution will continue at a higher rate (less growth but overseeing an ever growing economy).

We are currently experiencing a transition phase and every transition implies uncertainty and the unknown. Even more so when the principal player in this transition is a murky one as is the economy of China. It is unsure what will come as a result of the structural changes and production model processes and this challenge is a big one. We do know, roughly, where we are headed in the long-term, although the tortuous path at arriving there is unclear. The dizzying rise in the debt of the country and the industrial overcapacity, to give some examples, are two such concerns for fear in this process.

Political authorities in China do not offer much clarity thereon. The objective of the reforms and of the change in the production model entails a change to the decrease in growth (less growth, but more sustainable). This trade-off is bearable as long as the drop in growth rates is minimal and doesn’t jeopardize the main goal of the decision-makers: maintain stability and order. For this reason, and given that there were signs of a significant downturn (according to criteria established by China’s political party), new fiscal and monetary incentives have been implemented, which seems to be in contradiction to reform objectives.

This transition provides the perfect breeding grounds for a powerful return to a volatile atmosphere. Market players try to imagine what is currently happening and what may happen in the future. Among so many perplexities, it becomes difficult to know what to expect based on news, rumors and whatever the current trend happens to be.

Some quotes come to mind from the book “The Market as an Economic Process” by the Austrian economist Ludwig Lachmann, and illustrate what is happening in this particular case and the nature of the market in general.

“The market process is kept in motion by unexpected change and divergent expectations.

Changing situations have to be interpreted before they are acted upon.

What men adjust their plans to are not observable events as such, but their own interpretations of them and their changing expectations about them. Time cannot elapse without the state of knowledge changing.

Divergent and volatile expectations of course are neither rational nor irrational, they are a fact of economic life.“

In recent months, expectations seem to have remained on the negative side of the pendulum, with the focus being the risks and problems that China’s growing economy has presented. Nevertheless, as Jacobo Areaga of BrightGate Capital points out in this excellent article about characteristics of the consumer in China’s middle class, the potential coming out of Asia in the long-term promises to be very significant. Change is underway, and the importance of the service industry is increasingly growing.

Furthermore, when placing the spotlight on the global panorama, we can see that if China suffers a serious downfall, other countries are available to take its place. In this case, India.

A recent report out of The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies indicates that India is on the verge of replacing China as the driving force in the growth in oil demand. In fact, in 2015, India was the number one force in the growth in oil demand of all non-OCDE countries. According to researchers, a takeoff in India’s oil demand would be of a production rate comparable to that of China in the 1990’s.

Different factors are encountered when considering this projection: the boost driven by recent significant economic growth – which was benefitted by the collapse in oil prices -, structural changes such as better stimuli to the economy, programs aimed at investing in infrastructure and the promotion of industry through economic policies.

Apart from oil, let’s consider other factors when comparing China and India.

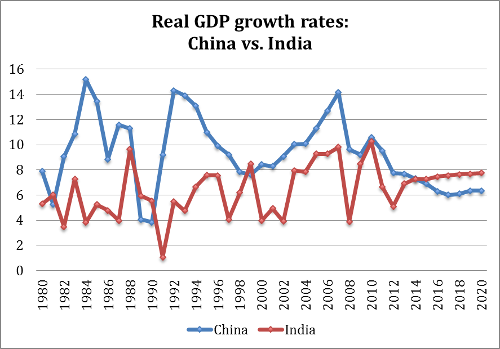

Source: Graph self-prepared using data from the IMF, World Economic Outlook. Percentages used are estimates after 2015

Since 1980. China’s growth rate has been substantially higher than that of India’s which shows almost no increase when comparing the last year’s with the first year of the chart, but as of 2015 and projecting what is to come, this has and will continue to change. Current projections (which most certainly will not be fulfilled) show a positive growth differential in favor of India by about 2 percentage points.

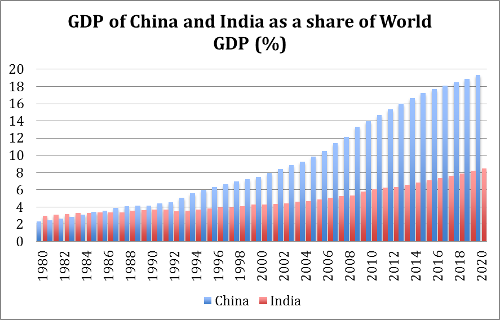

If we take a look at the weight that both economies have on the Gross World Product, we see that in 2015 China is estimated to attribute for a little more than 17% compared to India with only 7%. In the 1980’s, India accounted for a larger percentage than China, which demonstrates the enormous absolute and relative growth seen by China.

Source: Graph self-prepared using data from the IMF, World Economic Outlook. Percentages used are estimates after 2011

We can conclude from this comparison that it is still too soon for India to even come close to China in terms of the importance of the influence it has on the global economy, but it does play an ever-growing important role.

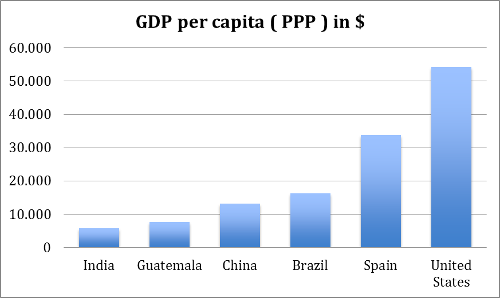

Another factor to take into account when evaluating India’s enormous growth potential: In 2014, India recorded a per capita GDP of only USD$6,000, compared with the per capita GDPs of Guatemala with USD$7,500 and China with more than USD$13,000. Incidentally, it is estimated that in 2017, China will surpass Brasil in terms of GDP per capita.

Source : Graph self-prepared using data from the IMF, World Economic Outlook. Year used: 2014. Data for Guatemala and India are estimates

In a transition phase such as the one we are currently seeing, where investors try to project what’s to come, incorporate new variables or eliminate others that become obsolete, reinterpret new and existing information…its seems that it may be convenient to have a look at the current case in India, without underestimating the potential that China continues to represent.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Ángel Martín Oro

Ángel Martín Oro is VP of Spain at UFM Market Trends in collaboration with Instituto Juan de Mariana. He is also a PhD-candidate in economics. He is also a senior consultant at iDen Global and was previously an editor at the financial portal inBestia.com. In addition, he is a professor of the OMMA Master of Economics. He is the author and co-author of numerous reports and articles, published in Spanish and international media, such as the Wall Street Journal and the Cato Institute.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions