What Is Really Happening with Venezuela’s Gold?

When a human body does not receive the nutrients it needs, it begins consuming its fat reserves, if any. If no fat reserves remain, the body begins to break down muscle tissue — also called “catabolism.” As a last resort, the body ends up consuming its own muscle mass.

It could be said that this phenomenon also occurs in economics. Whenever a country has a trade deficit and suffers a crisis, it becomes next to impossible to raise taxes or finance itself abroad. The only option that remains is to finance itself through more desperate last-resort measures — akin to an organism that feeds on its own muscle mass. This effect could be called “economic catabolism,” and this is precisely what is happening in Venezuela. The country is burning through its gold reserves as a last resort to weather its current economic crisis.

To understand what is happening with Venezuela’s gold reserves, one has to go back in time. Hugo Chávez did not have the financial troubles that Nicolás Maduro is currently experiencing, since oil prices allowed Chávez to generate sufficient tax revenues to cover the country’s spending. High international oil prices allowed the Venezuelan government to disregard the rest of the economy, turning the country into one of the most dependent on oil prices in the world. In recent years, oil exports account for 95 percent of total government revenue, with another 4 percent financed by government exports of other commodities. A mere 1 percent represents tax income from Venezuela’s impoverished private sector.

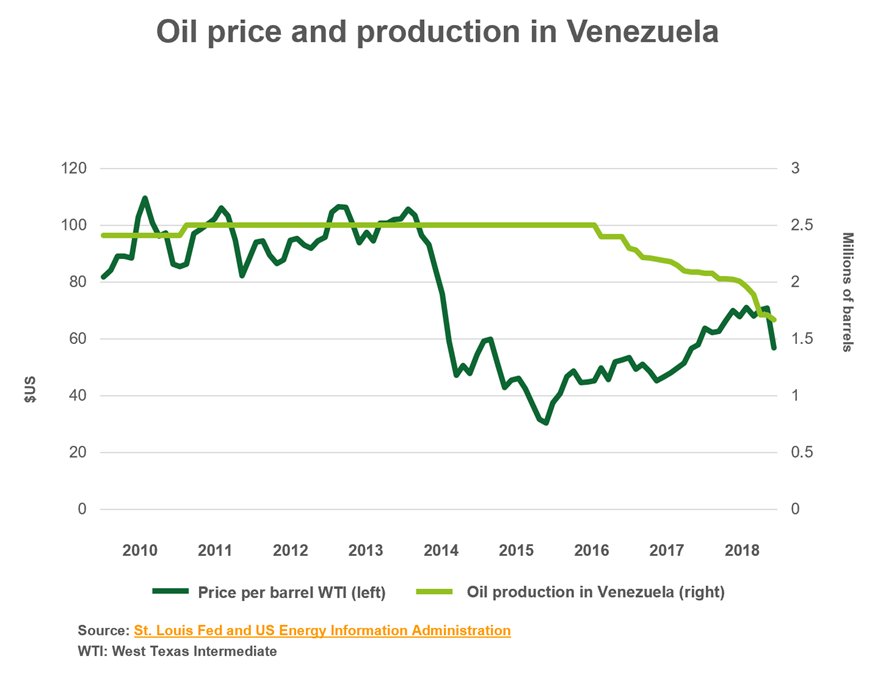

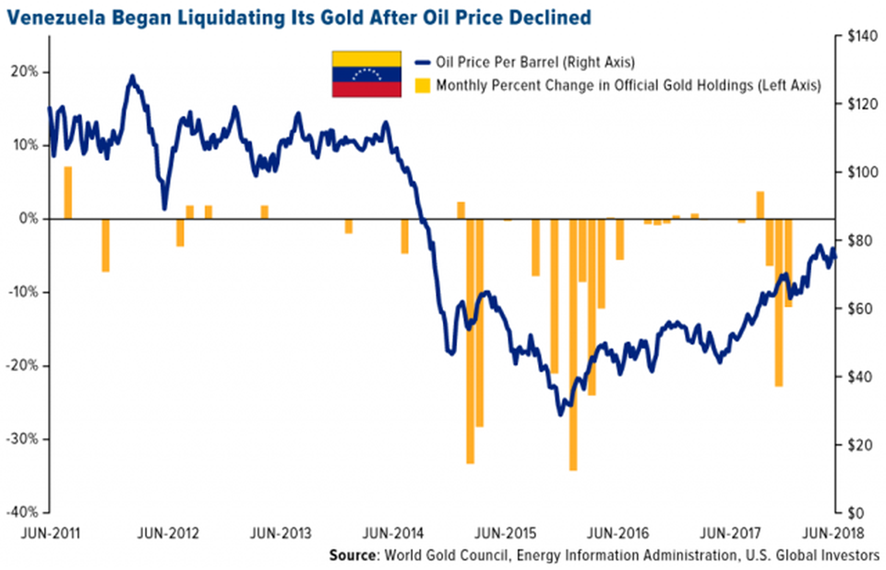

But as we know, crude oil prices collapsed after Chávez passed away in 2013. Prices fell from approximately $100 a barrel in 2013 to $57 a barrel in 2014. The oil price even reached a low of $35 a barrel in February 2016, but recovered to its current levels (at the time of writing, oil prices stood at $57 a barrel). Despite the recovery, Maduro has never enjoyed the same crude oil prices as Chávez.

Unlike Maduro, Chávez benefited from crude oil prices exceeding $100 a barrel and higher levels of oil production.

Falling Crude Oil Prices and the Subsequent Trade Deficit

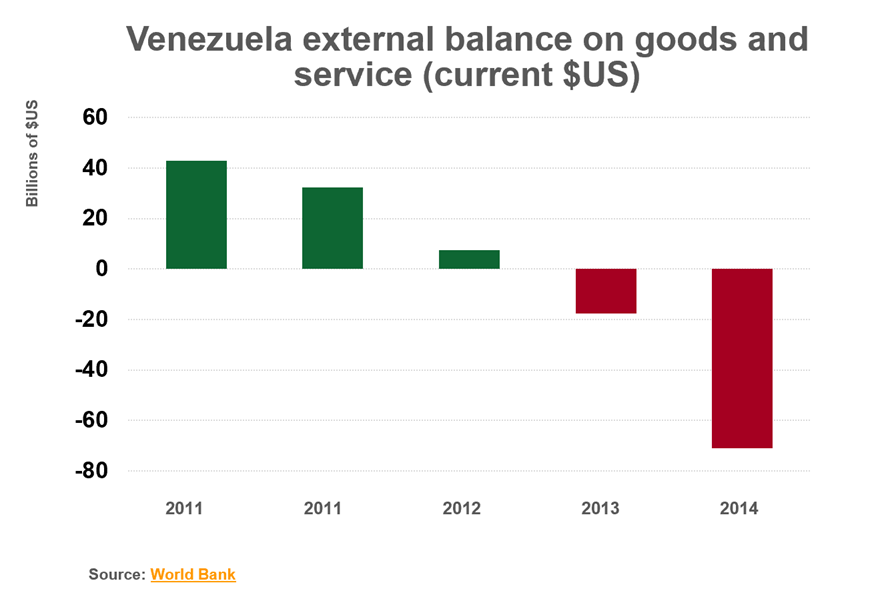

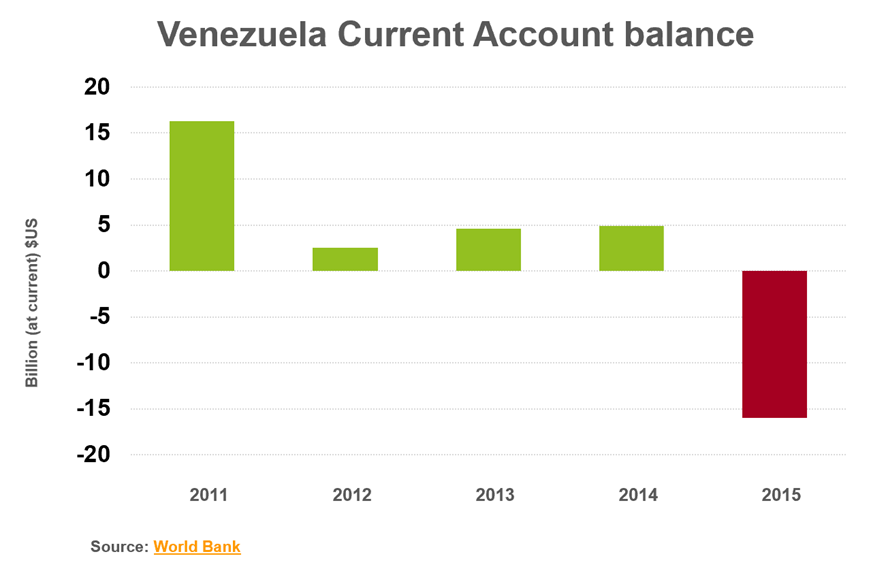

Whenever an economy is completely dependent upon a single export, while at the same time production collapses, the logical outcome is a fall in revenue from exports. If imports are not reduced to compensate for lower exports, the country has a negative trade balance.

Having a negative trade balance is not a bad thing in itself, as long as there is someone willing to finance the deficit. Venezuela’s problem has been precisely that there have been no such people. A fall in the trade balance has been coupled with a complete lack of credibility in international capital markets. In other words, the ability to finance the trade deficit abroad has been restricted.

Solutions to Finance a Trade Deficit without Access to International Markets: Printing Money

In recent years, Venezuela has explored different options to solve its financing problem.

The first option governments usually consider in these situations is to print money — and Venezuela has printed a lot in recent years, producing mounting inflation. According to Bloomberg, Venezuela introduced $10 billion in banknotes into circulation in 2015 alone. By comparison, the US, with ten times the Venezuelan population, introduced $7.6 billion in new banknotes into its economy that year.

Not all bolivar banknotes are printed in Venezuela. This work is done by foreign companies specialized in printing banknotes, specifically Britain’s De La Rue, France’s Oberthur Fiduciaire and Germany’s Giesecke & Devrient. Private planes flew from Europe to Caracas loaded with bolivars. These banknotes were transported at night with a large security device to the Central Bank of Venezuela to put them into circulation. But in March 2016, problems arose with these European suppliers. Venezuela failed to pay the European companies that printed the banknotes. According to Bloomberg, the largest banknote-production company in the world — De La Rue — reported that the Venezuelan government owed $71 million in unpaid bills.

Banknote producers do not usually have collection problems, because when clients do not pay, they simply keep the bills that they produced and exchange them for other currencies. The problem is that not even the banknote producers wanted the piles of paper that they were producing; each banknote has too little value.

When Nobody Wants to Print Your Bills: Sell Your Gold Reserves

What solution remains for a government to keep an economy afloat with a current-account deficit and no possibility of printing new notes? Sell hard assets that you can still sell for foreign currencies.

Venezuela has not only one of the largest in-ground gold reserves in the world, but until recently also had one of the largest reserves of monetary gold. What is the difference between monetary gold and non-monetary gold? Monetary gold is essentially bullion. Central banks then hold bullion as part of their assets.

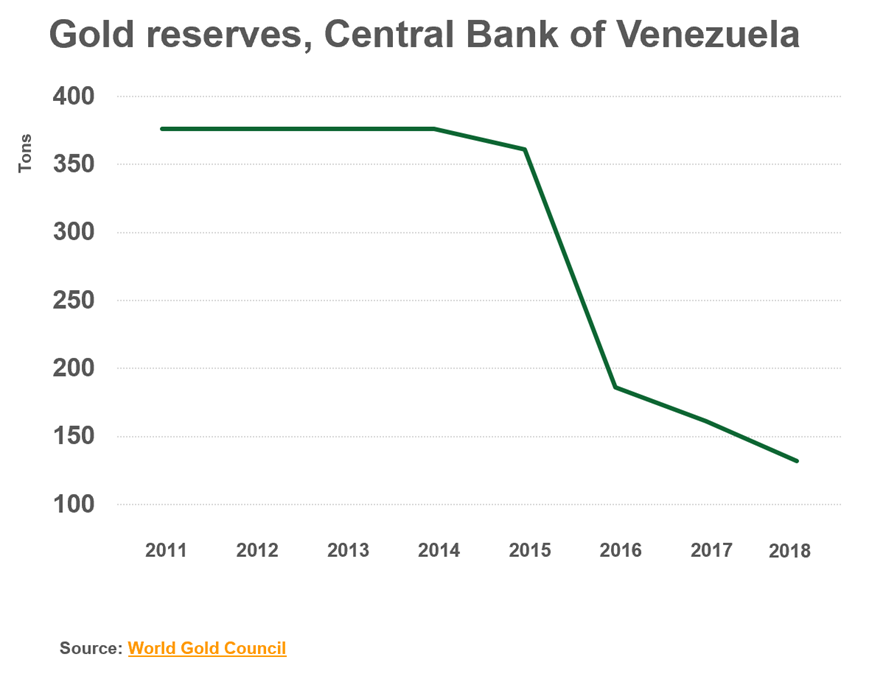

Just a few years ago, with more than 360 tons of gold, Venezuela ranked sixteenth in the world in terms of monetary gold. It had the most reserves in Latin-America, followed at a great distance by Mexico with 120 tons. If you compare this number to the 504 tons of the European Central Bank — an economy more than twenty times Venezuela’s GDP — it is a very large number.

However, since Maduro became president, the country has burnt through its gold reserves. In fact, Venezuela has sold the most gold in recent years in the world.

Why Are Venezuela’s Gold Reserves So Much in the News?

In recent days, there has been a lot of news about Venezuela’s gold reserves. The reason is simple: Venezuela’s gold reserves are the government’s last resort to pay officials and its army — institutions necessary to maintain Maduro’s rule.

It is a common practice for a central bank to store its gold reserves abroad. Yet in 2011, Chávez initiated a program of repatriating $11 billion of Venezuelan gold kept safe by other countries’ central banks. Maduro continued this repatriation program until some central banks, such as the Bank of England, denied him $1.2 billion worth of gold at the end of January. In spite of Maduro’s insistence, the Bank of England’s decision to not comply with Maduro’s request could also be justified in order to guarantee the collection of Venezuela’s unpaid debt. In August of last year, Venezuela defaulted on approximately $1 billion in bonds. Specifically, the bond issue of August 2018 was not repaid.

Time Is Running Out for Venezuela

According to Reuters, Venezuela still had 132 tons of gold in November. A few years ago, the figure was almost three times higher. In 2018, Venezuela exported gold worth $900 million to Turkey, among other countries.

Venezuela is struggling economically. It needs foreign currency to import the supplies it doesn’t produce and pay government officials and the army. Maduro’s plan to survive this economic crisis is, however, straightforward: exhaust all of Venezuela’s monetary gold reserves until no gold is left.

According to Flightradar24, during the last days of January a Russian Boeing 777 made several trips between Caracas, Dubai, Moscow and Shanghai.

The Venezuelan legislator José Guerra warned that the true intentions of the plane could be to “take 20 tons of gold from the vaults of the country’s central bank.” Officials of the Central Bank of Venezuela confirmed to the Spanish newspaper El Mundo that on January 28, at night, “they took out a batch of gold — valued at around 850 million dollars — from its vaults.… Nobody knew where the gold went and why it was sold.” These events received extensive press coverage, which seems to have prevented the mysterious plane from leaving Maiquetia’s airport with Venezuela’s gold reserves. According to Bloomberg, despite the evidence of the Russian plane in Caracas, Russian finance minister Simon Zerpa denied the fact.

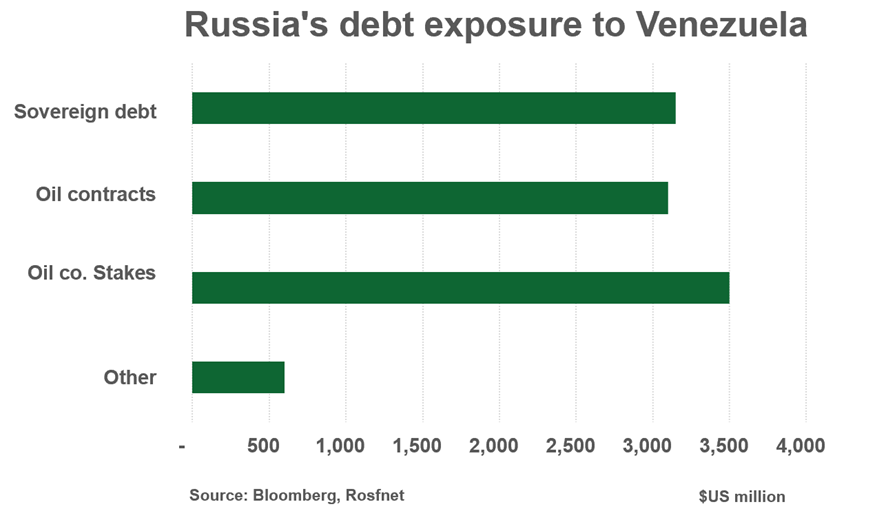

However, Russia did say that it will give all necessary support to Nicolas Maduro. The reality is that Russia has a lot of interest in avoiding Venezuela’s collapse. Russia has $10 billion in outstanding loans to the Venezuelan government, and some doubt that the Venezuelans can afford the repayment of $100 million this month.

In addition, the purchase of three tons of Venezuelan gold by a United Arab Emirates company has been confirmed. “On January 21, Noor Capital purchased approximately three tons of gold from the Central Bank of Venezuela, according to international norms and laws in force as of that date,” the Abu Dhabi firm said in a statement.

The gold was sold only a few days before the US imposed new sanctions on Venezuela. According to Reuters, Nicolas Maduro was planning to sell another fifteen tons of gold reserves. Yet given the diplomatic recognition of the interim president Juan Guaidó, along with the sanctions, Maduro’s plan to sell off gold reserves could be frustrated.

How Long Does Venezuela Have?

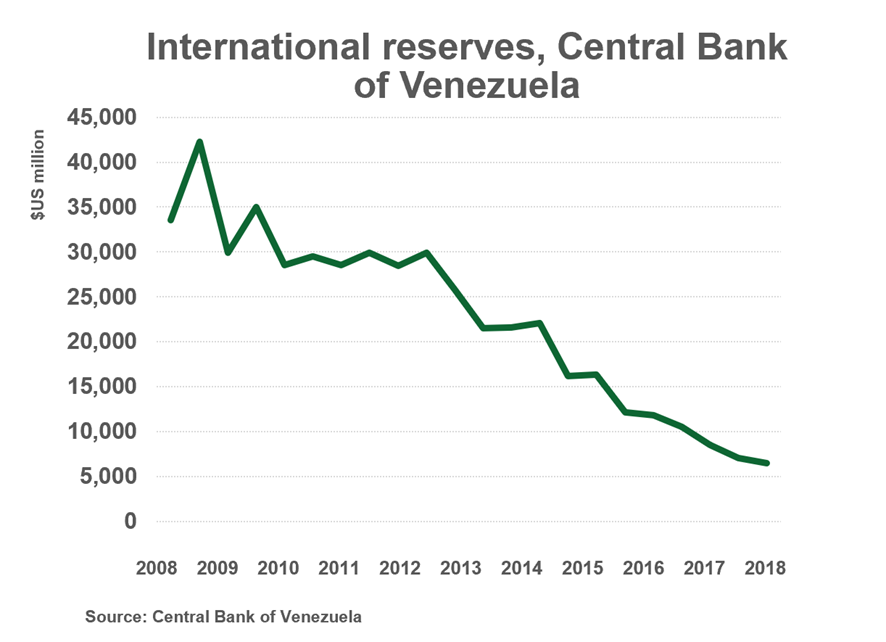

Assuming that the Central Bank of Venezuela has international reserves of about 130 tons of gold, minus the 17 tons that it cannot use (since they are held at the Bank of England), Venezuela has only 113 tons of gold available — in other words, approximately $5 billion worth. Ten years ago, Venezuela’s reserves were worth $40 billion.

In a decade, the Central Bank of Venezuela has consumed approximately $35 billion in international reserves.

If, despite the sanctions, countries are still willing to buy an average of 58 tons of gold a year from the Central Bank of Venezuela, the country’s reserves would last a little over a year. However, with the debt repayments that the government faces — much of the money is due to China and Russia — Venezuela would already be bankrupt and not even the gold reserves that remain in custody of the Venezuelan central bank could keep Maduro’s government afloat.

Venezuela is agonizing. One of the richest countries in the world in natural resources is dependent upon humanitarian aid. Venezuela clearly proves that rich countries are not necessarily the ones endowed with abundant natural resources. Economic progress is based on the principles of legal security, private property rights, and solid institutions that ensure compliance with the rule of law. All these principles have been deteriorating in recent years with expropriations, random sentences, and the discrediting of the National Assembly by Hugo Chávez and Nicolas Maduro.

In short, Venezuela has shown us the importance of economic policies that facilitate the economic progress of a nation. When such economic policies are absent, all of the natural resources or gold in the vaults of a central bank cannot prevent a country’s collapse. In the coming months — absent help from China or Russia — we will see the demise of the Venezuelan system due to economic catabolism.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Kike Briega, CFA

Kike completed an MBA at IESE Business School with an exchange at Chicago Booth. He has a financial certification CFA (Chartered Financial Analyst) and has worked in investment banking, corporate strategic consulting, as well as in the world of development in Africa and Central America. His personal blog is www.fisgonomics.com.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

What you have not said in this article is that USA arbitrarily impose “embargos” ruin countries’ economies as well, so – in my opinion -this article is biased and polirised .

Are you scared to say the facts? or you are not a truly professional?