Financial Crypto Panic

The world of cryptoassets is experiencing its own kind of banking panic, though those were historically confined to the financial world. Many of the developments we are seeing there have parallels in traditional financial markets.

In this article we are going to see how the crypto world has been making inroads into the two major traditional financial markets: the capital market and the money market. We are going to analyze the crypto money market (that is, stablecoins) in depth, and we are going to see how what we are experiencing in this market has many parallels with banking panics.

- For a detailed analysis of the Tether stablecoin, read this article.

- For a detailed analysis of the TerraUSD stablecoin, read this article.

First, it is necessary to analyze crypto incursions into the field of traditional finance, beginning with initial coin offerings (ICOs) and capital markets.

The Crypto World in the Realm of Traditional Finance: Capital Markets

In every wave of adoption and price increase in the world of cryptoassets, some development occurs that is reminiscent of the development of traditional finance over the centuries.

In the moments prior to the crypto crash of 2018, there was a massive issuance of now-almost-forgotten ICOs. The term “initial coin offering” is intentionally similar to a term in traditional finance, “initial public offering” (IPO).

IPOs represent a mechanism for raising capital for companies that have not yet gone public. In fact, a company goes public through an IPO; prior to that, companies are private (in other words, unlisted). Through an IPO, a company offers shares to new investors and starts trading on a secondary market—that is, a stock exchange.

Cryptocurrency ICOs are very similar to IPOs but in the crypto world. ICOs were designed to finance new cryptocurrencies through a mechanism similar to crowdfunding. After a new cryptocurrency was launched, those who funded it through the ICO obtained a fraction of the new issue of that cryptocurrency. However, the ICO mechanism could be extended, and it was. ICOs began to be used as a way to obtain funding in the same way that IPOs were used in traditional finance. When an entrepreneur (typically in the crypto market) needed funds for a project, they would undertake an ICO and secure investors for their project. These investors would share in the profits the project might generate through acquiring newly generated tokens, which are a kind of equity in a blockchain.

Thus, the crypto market created its own way to replace the traditional capital market. ICOs took on some of the typical functions of investment banking.

Many of these ICOs ended up being fraudulent, so the mechanism fell into disrepute. ICOs have basically been in disuse since then. Despite this, the idea is very powerful and not inherently fraudulent (no more than any company’s equity issuance). The market may simply need more time and perhaps specialized intermediaries who are able to distinguish scams from legitimate businesses. In any case, since the crypto market crash in 2018, the ICO fever has faded.

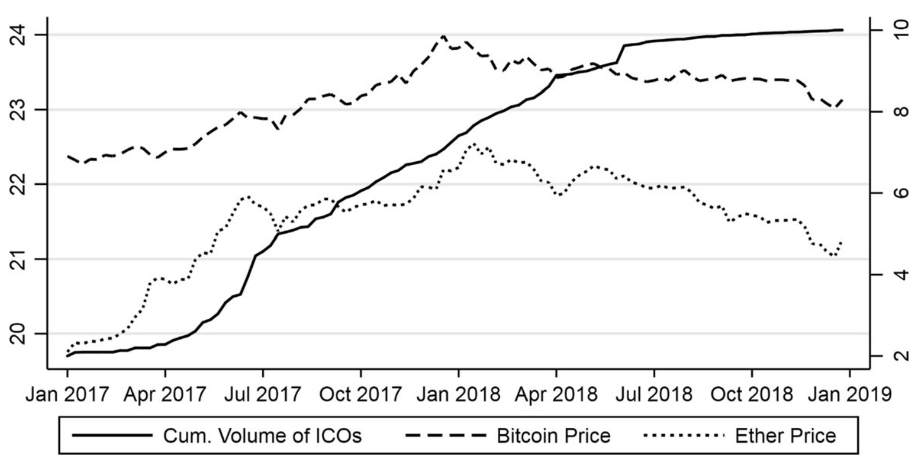

It can be seen in figure 1 that the ICO market began to deflate shortly after the prices of the major cryptocurrencies started to fall at the beginning of 2018.

Figure 1: Cumulative Volume of ICOs, and Bitcoin and Ethereum Prices

Source: “Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs): Market Cycles and Relationship with Bitcoin and Ether” (d-nb.info)

The Crypto World Enters the Money Market

The year 2020 ushered in a new crypto wave and with it new developments poised to emulate and perhaps replace the functions of traditional finance. This time, the crypto world began to respond to a market need to be satisfied by what traditional finance usually refers to as the money market. Commercial banks (the banks we all know), and, to a lesser extent, other institutions like money market funds, usually broker the money market.

The crypto world began to take an interest in stablecoins, which are nothing more than cryptocurrencies that have fixed exchange rates with the dollar or another currency that is widely used worldwide. The idea is to avoid the typical volatility of the crypto world. Stablecoins are also very useful for exchanging other cryptocurrencies without having to go directly through a dollar bank account or for making international transfers.

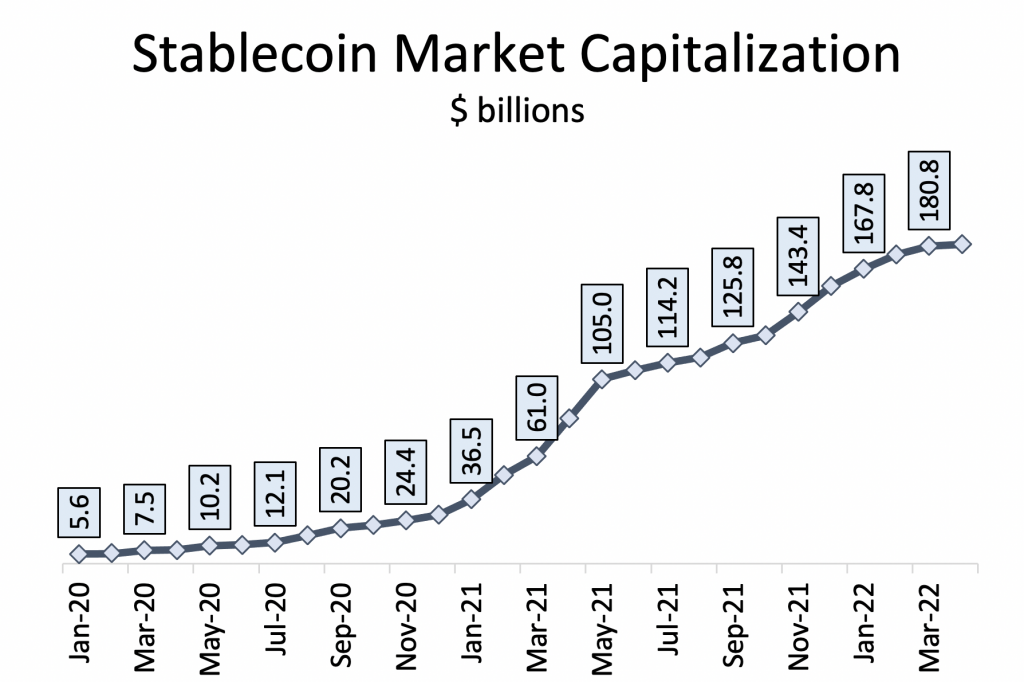

Although stablecoins have been around for a while (it has been possible to trade with the most commonly used stablecoin, Tether, since 2015), the real explosion began in 2020. In January 2020, the total market capitalization of stablecoins was only $5.6 billion. By the beginning of April 2022, this figure reached almost $182 billion. In other words, the market value of stablecoins has increased by thirty-two times in just over two years.

Source: Statista

Thus, although the idea and the technology were already developed, the technology had not been popularized (as with ICOs). Therefore, stablecoins are part of the new wave of crypto popularity, and, this time, the foray is into the money market.

ICOs fell into disrepute with the downturn of the crypto market in 2018. Likewise, stablecoins have thousands of eyes on them now. Can they survive?

Crypto Financial Panic: Parallels with Traditional Banking

Several stablecoins have already broken their fixed exchange rate with the dollar. This has a parallel with traditional finance, one that hardly anyone remembers anymore.

Until not so long ago (perhaps a little more than a century),[1] when a bank experienced serious financial problems, the so-called par price was sometimes broken. The par price is more or less an exchange rate between a dollar in the bank and a dollar out of the bank. Most of us don’t care about that price, because we are so used to it being equal to one that we don’t even imagine that a dollar in the bank could be anything different from a dollar in hand. But when there were no central banks (or when central banks were private), a bank could get in trouble and, if it did not have good assets[2], it would have nobody to come to its aid. When this happened, the par price would break; that is, a dollar inside a bank would have a lower price than a dollar outside the bank.

The par price has been broken on countless occasions throughout history; specifically, it breaks every time a bank fails to deliver the money requested by a depositor. This means that there are depositors at that bank who are willing to sell their dollars at that bank for a price lower than a dollar in physical currency. The last time this happened was in Greece in 2015.

Why would a bank not be able to pay its depositors? This happens when it has poor-quality assets (short-term, low-risk assets are usually high-quality [and low-return] investments). When a bank, for whatever reason, faces claims from its depositors, it needs to sell assets to raise money to pay them. When a bank is solvent and liquid, it can meet any demand from its depositors without too much trouble. But if a bank has been taking unnecessarily high risks and one of the investments it made goes bad, then its assets are unsalable or salable at a very low price and this makes it impossible to pay depositors.

How does this tie in with the cryptocurrency market?

Crypto Financial Panic: Stablecoins as Bank Proxies

Stablecoins are very similar to traditional banks (or even money market funds, as explained above). They have what is usually called collateral (assets backing the currency). This collateral differs a lot between stablecoins, but it has exactly the same function in all of them (and the same function as assets in the banking sector): to ensure that the par price does not break.

When the demand for a stablecoin grows, there is no problem. New stablecoins are generated, and assets that act as collateral for the stablecoin are purchased.

A problem can arise when demand for a stablecoin decreases (especially if it plummets). Any asset that registers a sharp selloff in the market simply drops in price. But the stablecoin’s price cannot fall since its utility comes precisely from maintaining the par price. In this case, the quality of the collateral is crucial. When there is a sale of the stablecoin, the collateral must be sold to withdraw from the market the amount of stablecoin needed to counter the oversold market. As in the banking sector, the assets backing the currency are key to stabilizing its value. If the assets cannot be sold at the critical moment or must be sold at very low prices, it may happen that not enough stablecoin can be withdrawn to counteract the selling of the stablecoin. Then the adjustment occurs by dropping the price of the stablecoin. But in stablecoins, which are intended to be very safe assets, a fall in price is synonymous with trouble, which pushes more people to sell, which triggers new price drops.

Crypto Financial Panic: A Typical Bank Run

These problems with asset quality are what TerraUSD has had to deal with, as my colleague Olav explained in this article. We don’t know exactly how bad the problem is at Tether, although it seems that, for now, Tether has managed to reflate the value of its coin (that is, at least it has had assets valuable enough to counter the oversales recorded so far). These are the most notorious cases, but other stablecoins have also been affected, and all of them have been oversold in the market.

What triggers the distrust and overselling of stablecoins in the first place? Exactly the same problem that caused people to lose interest in ICOs: a fall in the cryptocurrency market.

Here the parallels with traditional finance are evident again. The solvency of banks is not usually called into question until the assets in which the banks invest fall in price (nowadays, a real estate crisis makes everyone in the banking sector very nervous). If a particular bank has been investing in a very specific type of asset, a fall in the price of that asset can trigger a bank run.

Exactly the same thing has happened with stablecoins. A steep drop in the cryptocurrency market (and cryptoassets in general) has led to reasonable doubts about the ability of these coins to maintain parity when the price of the collateral for many of them was plummeting.

The TerraUSD case is striking. Its backing was a token called Luna (a token is a cryptoasset similar to the equity of a traditional company). When the price of Luna started to plummet, doubts started to surface about the possibility of converting TerraUSD (the stablecoin) to the par price. The sale of TerraUSD forced the sale of its backing to stabilize its value. This generated further drops in the price of Luna and more instability for the stablecoin. It was a textbook bank run.

Do We Need a Central Bank to Avoid These Problems?

There are two answers to this question. The short answer is: no, not at all. The long answer is below.

If collateral is the main problem, as I have been arguing, then the key question is: does central banking encourage the search for good collateral (that is, good assets to back the currency)?

The answer is another resounding no. In fact, central banking does just the opposite. Central banks, as lenders of last resort, privilege government debt as collateral for purely political reasons.[3] A central bank’s function as lender of last resort consists in extending financing to any troubled bank. That is, when a bank needs to pay depositors but cannot sell assets and no one else wants to lend to it, then the central bank will do so. When the central bank intervenes, the private bank no longer has to sell its assets.[4] This is how banking panics have been avoided for more than a century.

Central banks’ lender-of-last-resort function does not prevent private banks from choosing bad collateral but rather encourages it. Banks take more risk because they know they cannot fail in a liquidity crisis because the central bank will be there to save them if problems arise. In other words, the central bank gives the appearance of security (we all think that our deposits are safe), but in reality it is encouraging irresponsible behavior and shifting the consequences of it to all those who use a country’s currency. This is one of the reasons why inflation was one of the evils of the twentieth century and seems likely to continue to be one in the twenty-first century. In short, to prevent a bank from suffering, all the users of the currency suffer.

Thus, the central bank causes the consequences of bad decisions to be passed on from those who make them to the rest of us. It’s as if TerraUSD were saved by requiring everyone who owns Tether to suffer a drop in their currency’s value. It seems a bit unfair, doesn’t it? This is what central banks have been doing for more than a century, but we have become accustomed to a corrupt monetary system and have no memory of what true monetary freedom (and responsibility) means.

Conclusion

The world of cryptocurrencies is experiencing its own kind of bank run. But, far from being the problem that many suggest it is, perhaps it is just one more step in the process of discovering financial intermediation activities, which are so innate to humans that they have been with us at least as long as there have been great empires. Financial needs have been solved in many different ways over the centuries and are sure to continue to change in the future.

Legal notice: the analysis contained in this article is the exclusive work of its author, the assertions made are not necessarily shared nor are they the official position of the Francisco Marroquín University.

–

Notes

[1]For those of us who like history, talking about a century is similar to talking about last summer.

[2] Forgive the redundancy of the statement “If a bank has good assets, it never has problems,” but I use this phrase for didactic reasons.

[3] In the nineteenth century, the Bank of England operated a little differently.

[4] It pledges them as collateral for new loans from the central bank.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Daniel Fernández

Daniel Fernández is the founder of UFM Market Trends and professor of economics at the Francisco Marroquín University. He holds a PhD in Applied Economics at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid and was also a fellow at the Mises Institute. He holds a master in Austrian Economics the Rey Juan Carlos University and a master in Applied Economics from the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions