Does China Devalue Its Currency?

Trade tensions between the US and China continue to increase. In the penultimate drama in the conflict, Donald Trump has accused China of manipulating its currency to illegitimately increase its competitiveness, and the US government has officially designated China a “currency manipulator.” Accusations that the Chinese government engages in currency manipulation are not new. They date at least to 2006, when Hank Paulson, ex-secretary of the US Treasury, began a round of negotiations with Beijing with the aim of increasing the value of the yuan and initiating an opening into the Chinese financial markets.

The purpose of this article is to elucidate to what degree the Chinese government engages in currency manipulation[1].

Yuan vs. Dollar Exchange Rate: Since 2005 until 2019

Washington accuses Beijing of manipulating its currency primarily through movement of the exchange rate. The accusation is that the Chinese government devalues its currency in order to make its exports more attractive and gain competitiveness artificially.

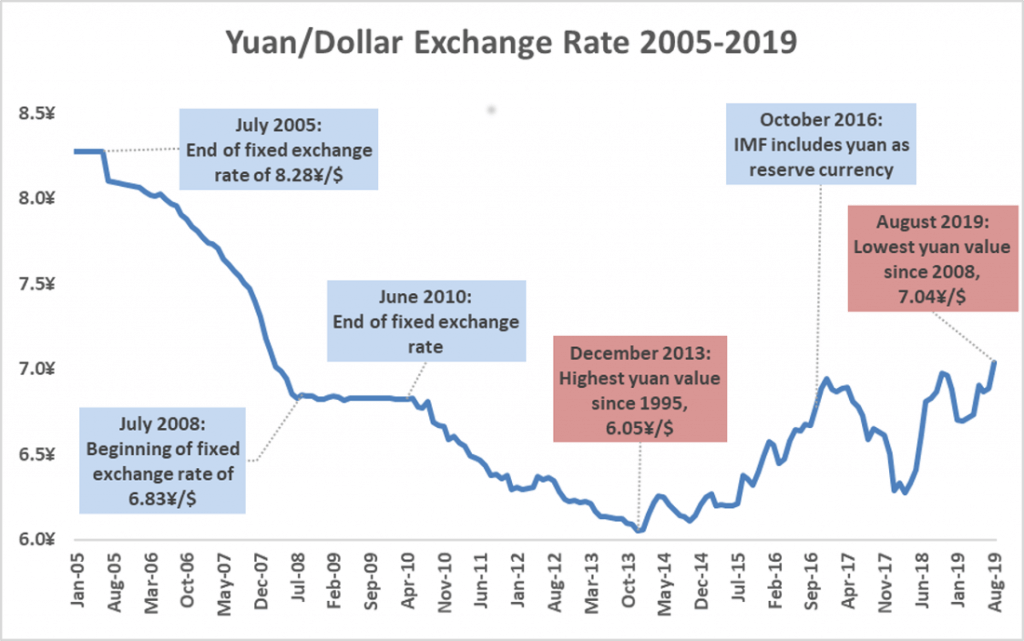

Until mid-2005, the People’s Bank of China established a fixed exchange rate between its currency and the dollar, at 8.28 yuan per dollar. The fixed exchange rate regime was reintroduced during the Great Recession; from July 2008 to June 2010, the yuan was at a fixed exchange rate of 6.83 yuan per dollar.

Between 2005 and 2008, and then again from 2008 until now, there was a dirty float regime for the exchange rate, in which China’s central bank established fluctuation bands for the yuan, and it was allowed to fluctuate within those bands. In practice, this dirty float ends up functioning as an exchange rate managed directly by the central bank. The graph shows the movement of the exchange rate in recent years, along with the changes in the exchange rate regime in China.

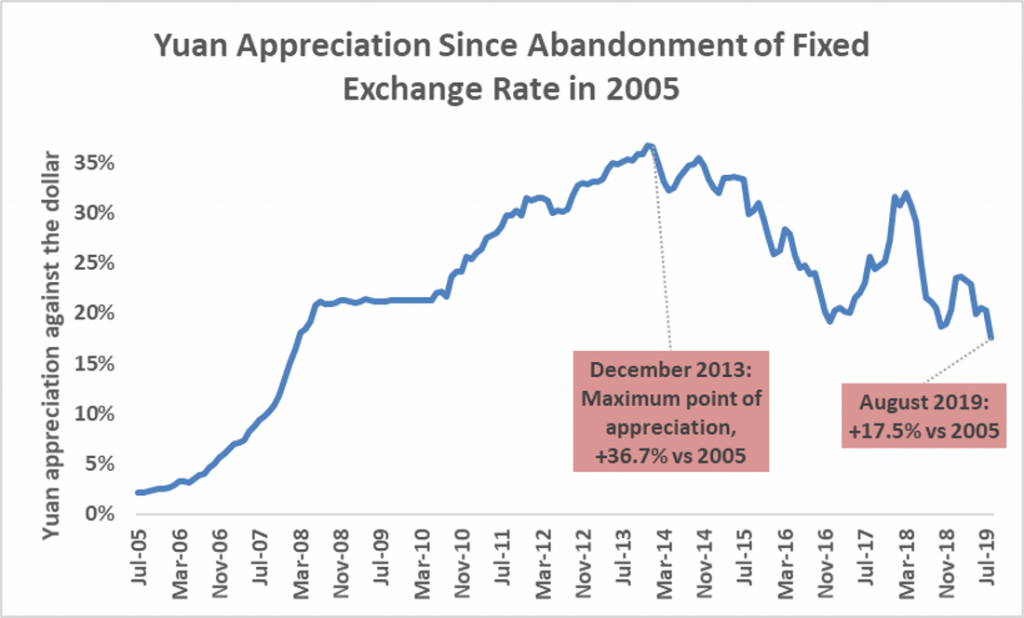

When a broader timeframe is taken into account, accusations of currency management for devaluation purposes are not very well founded. Since the fixed exchange rate regime was abandoned in July 2005, the yuan has steadily gained value until 2014. However, from 2014 to August 2019 there has been considerable devaluation. Despite this, the yuan today is still 17.5 percent more valuable in dollar terms than in 2005.

The Real Exchange Rate: The Effect of Domestic Prices

To see the real increase in competitiveness that the exchange rate can provide, we must take into account the real exchange rate. In this way, for there to be a gain in competitiveness, any depreciation of the currency must not be followed by an increase in internal prices. In spite of this, these gains in competitiveness tend to be transitory and are often associated with other problems.

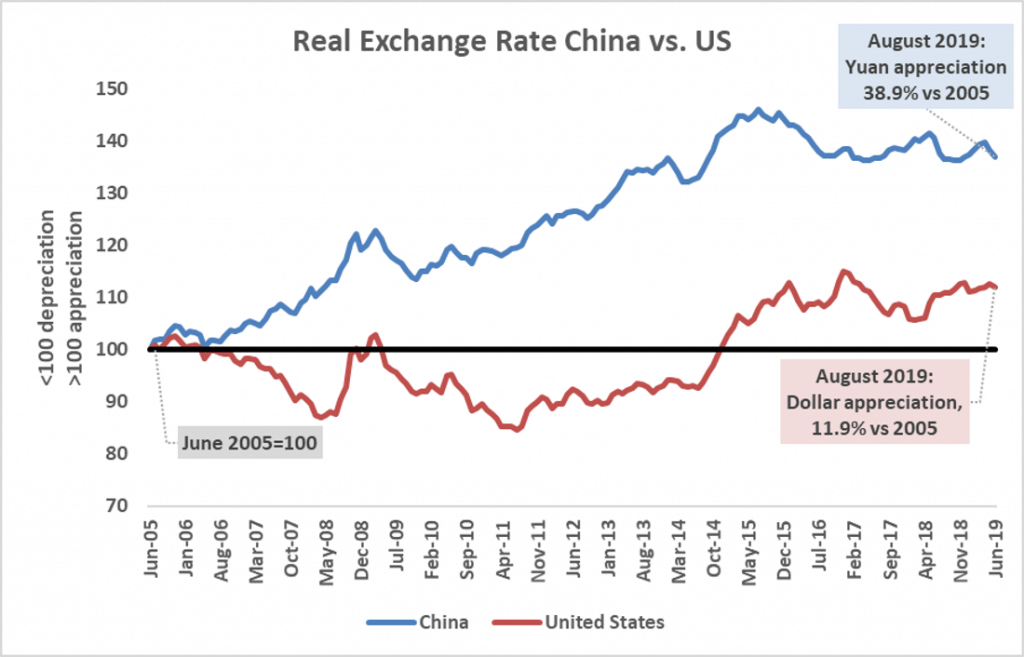

Let’s see how the real exchange rate of the US and China has moved since 2005. This indicator measures the movement of the real exchange rate of the country in question against 143 countries (and is weighted by the importance of each of the country’s trading partners).

The way to read the graph is as follows: a value of 100 indicates that the country has not lost or gained competitiveness through the exchange rate (compared to the situation in 2005). A value greater than 100 implies loss of competitiveness against business partners due to the real exchange rate. A value less than 100 implies a gain in competitiveness against business partners due to the real exchange rate.

As we can see, the Chinese currency has appreciated by almost 39 percent from June 2005 to August 2019. In the same time period, the US dollar has appreciated by 11.9 percent.

Therefore, it seems that once again, when a sufficiently long time period is taken into account, criticisms of China’s currency manipulation are unfounded.

The Impossible Trinity

In economics, the trinity is understood as the attempt by the monetary authority to pursue the following three policies simultaneously:

- A fixed or centrally managed exchange rate

- Autonomous monetary policy (for example, the CB setting a discount rate)

- Free movement of capital

The impossible trinity implies that the monetary authority must dispense with at least one of the three previous points.

Monetary policies that diverge between two zones tend to be reflected in the exchange rate and inflation levels (external price and internal price of the currency). If a zone has a very expansive monetary policy, it is expected that it will have higher inflation and that the exchange rate will depreciate. (For a detailed explanation of the theories that explain the movements of the exchange rate, click here.) If you want to prevent the exchange rate from moving when monetary policy is implemented, controls must be extended to the free movement of capital. This is precisely what China does.

Therefore, China maintains a managed exchange rate while aiming to have an autonomous monetary policy. The only thing left then is to dispense with the free movement of capital.

The US has been exerting pressure on China for years to eliminate, or at least soften, capital controls and to stop intervening in its exchange market and make the transition to a free floating exchange rate regime.

Pressure applied by western countries on China to change the exchange rate regime has worked to some extent. The bands that allow the yuan to fluctuate have been gradually increasing, leaving more and more space for market forces to act on the exchange rate. In 2005, the fluctuation band was only 0.3 percent of the exchange rate set by the central bank. Then, it was 0.5 percent in 2007, 1 percent in 2012, and has been 2 percent since 2014. However, the central value of those bands is still set by the central bank.

Capital controls have become increasingly weaker over the years. Before 2009, Chinese companies were prohibited from having dollars. Chinese citizens were also prohibited from making international trade transactions in Chinese currency and exporting currency outside of China. Therefore, it was almost impossible for a company outside of China to have yuan, and it was also very difficult for a Chinese company to have dollars. As a result, all international transactions had to pass through the central bank, which could set the price that it deemed appropriate for its currency.

Since 2009, China has released current account transactions, of which most are trade transactions. However, the restrictions on capital movement are still very intrusive. This implies that since 2009 the commercial flows have exerted pressure on the price of the yuan, although financial flows do not yet have that capacity (even though financial operations are often disguised as commercial operations with the goal of evading the capital controls). The opening of trade flows in dollars, together with a centrally managed exchange rate, forces China’s central bank to intervene in the money market by buying and selling dollars to maintain the fixed price of its currency if the exchange rate leaves the bands of fluctuation.

In 2016, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) introduced the yuan as a reserve currency when issuing special drawing rights (SDRs, the currency issued by the IMF). In return, some capital controls have been eliminated in China. This move aims to establish the Chinese yuan as a reference currency in international trade and as a reserve currency for other central banks.

It is assumed that China is seeking a gradual liberalization of capital controls while it simultaneously stops intervening in the exchange market in order to complete its transition to a free floating regime. Washington’s complaint is that while the transition takes place, the Chinese authorities are taking the opportunity to devalue their currency and give new impetus to Chinese exports.

The Recent Devaluation and How It Relates to the Use of International Reserves

Since 2014, the yuan has decreased in value against the dollar. The exchange rate has gone from 6 yuan per dollar to 7 yuan per dollar in August 2019, a devaluation of 16.3 percent. It is the recent movement of the yuan that is prompting the complaints from Washington.

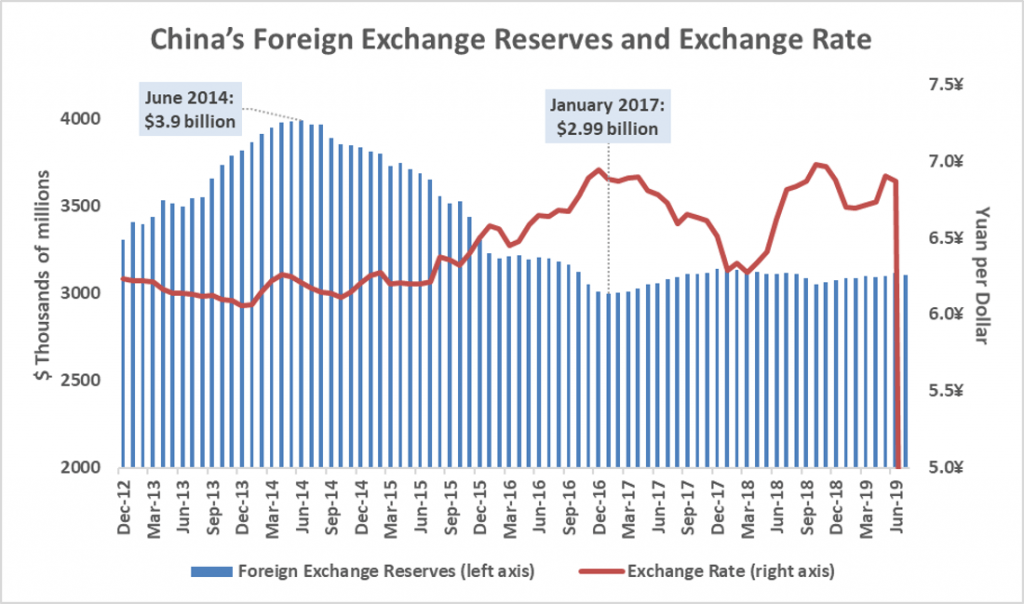

However, the recent exchange rate movements can be better explained by external reasons than by China’s devaluation policies. The People’s Bank of China controls the exchange rate by buying and selling dollars. When the exchange rate moves in one direction, the central bank “pushes” it in the opposite direction by buying or selling dollars until the exchange rate returns to the price set by the central bank. If there are pressures on the exchange rate to appreciate, this means that the central bank must buy dollars in the market and sell yuan. This in turn makes the dollar scarcer and the yuan more abundant, so the appreciation stops. This is what the People’s Bank of China has done since it allowed its currency to float in 2005, which caused huge dollar reserves to accumulate. On the contrary, when the exchange rate tends toward depreciation, this requires the central bank to sell dollars while buying yuan and taking them out of circulation. This is what happened from 2014 to January 2017 and much less markedly in 2018.

As can be seen in the graph, the People’s Bank of China has been selling enormous amounts of dollars in the market since June 2014 in order to defend the price of its currency. (It was literally fighting to avoid a devaluation.) After selling almost 25 percent of its reserves in just over a year, China’s central bank decided it wasn’t able to maintain the exchange rate and decided to gradually devalue its currency towards the end of 2015. In January 2017, it began a new phase of dollar accumulation. However, instead of continuing to accumulate currency, China’s central bank quickly decided to increase the value of the yuan again. In 2018, the opposite movement took place.

This means that, despite appearances, the People’s Bank of China is moving the exchange rate based on the situation in the market. Instead of accumulating or decreasing reserves, as it has done in the past, the bank is letting the exchange rate move instead of trying to fix it by purchasing or selling dollars in the market. In other words, one could say that the Chinese central bank has been taking measures that imply less intervention in the foreign exchange market since the end of 2015.

This does not mean that the People’s Bank of China doesn’t intend to use the exchange rate for devaluation purposes as another means of applying pressure in the escalation of protectionist measures in Washington and Beijing. However, and in light of the data currently available (August 2019), the recent exchange rate movements do not seem to be a response to a planned devaluation that is designed to increase the competitiveness of Chinese exports.

Conclusion

Criticism of China for devaluing its currency doesn’t seem justified if we take into account that both the nominal exchange rate and the real exchange rate of the yuan have appreciated considerably since 2005. In fact, the real exchange rate has appreciated more in China than in the US since China stopped using the fixed exchange rate regime in 2005.

The depreciation of the yuan since 2014 is more of a response to market movements than a planned devaluation to gain competitiveness illegitimately. China even spent almost 25 percent of its dollar reserves trying to sustain the price of the yuan between 2014 and 2017. Since 2015, and especially since the yuan entered the IMF’s reserve currency basket in 2016, the Chinese central bank has let its currency fluctuate more aggressively with fewer interventions in the exchange market.

Curiously, the US has been asking the People’s Bank of China not to intervene in the foreign exchange market for years, since at least 2006. Now that the Chinese central bank has decided to substantially reduce its interventions in the foreign exchange market, there are complaints from the US ー the very same government that has been demanding such a measure for more than a decade. The difference is that since the Chinese stock market crisis, the pressure on the yuan has been to depreciate and not to appreciate as in the past.

It remains to be seen if the Chinese government is as willing to let its currency appreciate if market pressures affect it again.

[1] In the current monetary and financial system, all countries manipulate their currency in one way or another. Therefore, our goal is to find out the degree of manipulation of the Chinese currency, not whether the manipulation exists or not.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Daniel Fernández

Daniel Fernández is the founder of UFM Market Trends and professor of economics at the Francisco Marroquín University. He holds a PhD in Applied Economics at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid and was also a fellow at the Mises Institute. He holds a master in Austrian Economics the Rey Juan Carlos University and a master in Applied Economics from the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Great explanation. Found it extremely helpful and answered the questions I had in my head.