The U.S. Money Market Is in Distress

At the Fed’s press conference of March 16, 2022 , Jerome Powell, Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, announces what everyone has been waiting for: the start of interest rate hikes to counter US inflation, which, by February 2022, rose to a 7.9% annual rate, a figure not seen since January 1981 in the U.S.

The Fed also published its plan to reduce the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. Specifically, the Federal Reserve begins its balance sheet reduction program (Quantitative Tightening or QT) on June 1 of that same year. In summary:

- For Treasury securities, up to a cap of $30 billion per month will be allowed to expire.

- For agency debt and MBS (mortage-backed securities), up to a maximum of $17.5 billion dollars per month will be allowed to expire.

- These amounts will be doubled three months after the reduction program’s start, that is, $60 billion for U.S. Treasuries and $35 billion for agency and MBS debt.

With this latest measure, the Fed intends to progressively reduce its balance sheet to pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels.

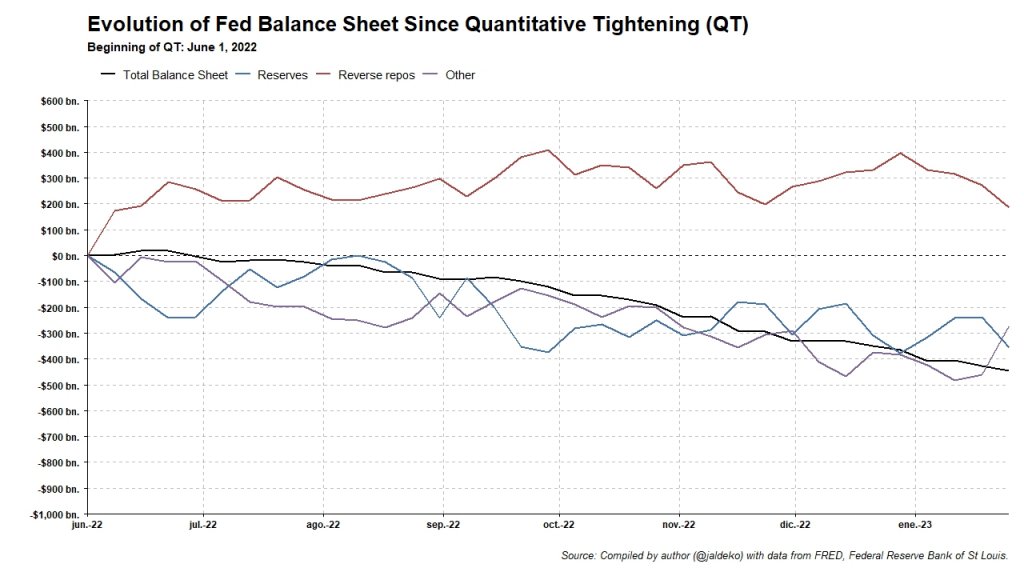

In the following graph, we can observe how the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has been shrinking with regard to various of its components.

Bank reserves and other components of the Fed’s liabilities have been reduced at an increasing rate, with the exception of reverse repos that will be discussed later. The reduction of the Fed’s balance sheet drains the enormous amount of bank reserves that banks hold among their assets as a result of the abundant reserve creation in the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2008 or Global Financial Crisis (GFC), as some English speakers call it.

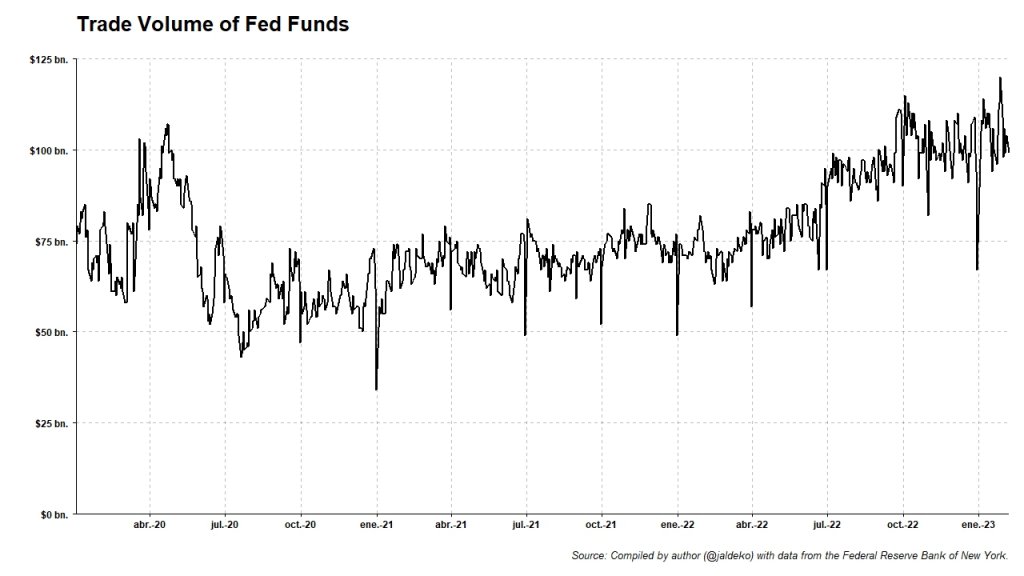

The banking sector depends on reserves for buying/selling and transferring money in the interbank market. When large amounts of excess reserves exist, the banking industry has no need to resort to the interbank reserve market, borrowing Federal Funds or Fed Funds, to conduct day-to-day operations. However, when reserves begin to run low, banks, among other depository and financial institutions, are forced to enter the Fed Funds market to borrow the necessary reserves that they will return at the end of the day.

As can be seen in the graph below, the volume of reserves lent in the Fed Funds interbank market is increasing, even exceeding levels during the pandemic. Although the data falls within a normal range, they do suggest that there is beginning to arise a certain need, which did not exist before QT, to enter the reserve market and borrow Fed Funds.

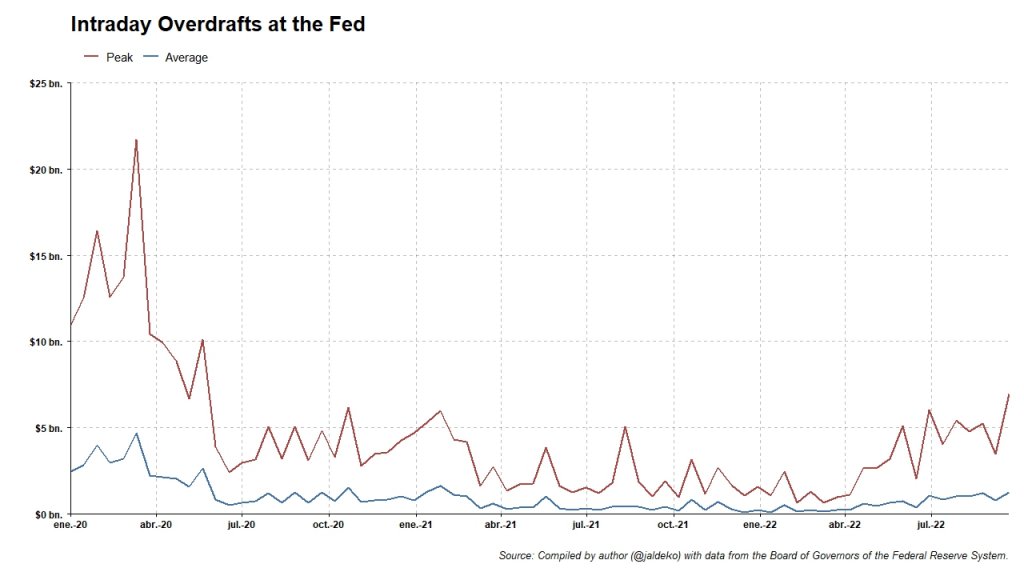

In the event that banks do not hold sufficient reserves available to carry out their daily operations, those financial institutions that have a master account with the Federal Reserve are allowed to maintain overdrafts against the Fed during the day (Daylight Overdrafts). However, such financial institutions are obliged to raise funds to clear the overdraft before the end of the day.

Therefore, we can observe an additional sign of distress in the U.S. banking system when analyzing the volume of intraday overdrafts that have occurred at the Federal Reserve.

As can be observed in the following chart, a rise in intraday overdrafts at the Federal Reserve suggests that some depositary institutions have had to maintain overdrafts with the Federal Reserve during the day in order to carry out their daily operations and subsequently borrow the amount of reserves required to cover the overdraft in the Fed Funds interbank market. The graph shows that these overdrafts have increased from the first quarter of 2022, particularly visible in the maximum or peak amount of overdraft. This period coincides with the start of interest rate hike cycle of the Federal Reserve. Unfortunately, the volume of overdraft is published quarterly and the latest data available is from September 2022. It is to be expected that this amount has continued to increase.

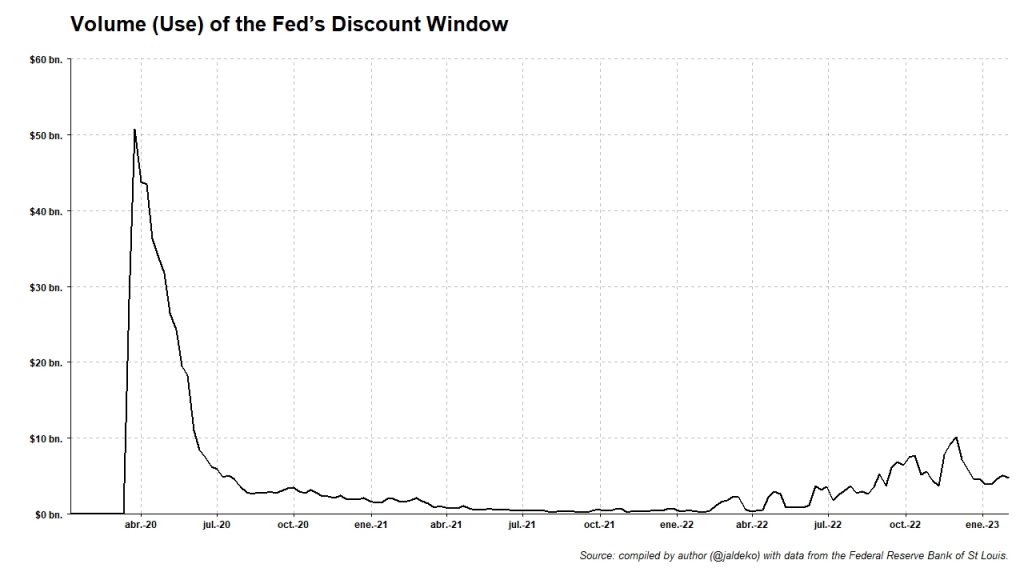

What happens if a financial institution with an account at the Federal Reserve is unable to obtain sufficient bank reserves at the end of the day to cover the overdraft it maintains with the central bank?

The Federal Reserve, through its discount window, will lend that institution the necessary reserves to cover the overdraft, granting it an overnight loan at a burdensome interest rate that it must repay as soon as possible. In fact, we can observe that Fed lending at the discount window has risen in the same period that overdrafts have risen.

To understand the increasing use of the discount window, it is necessary to mention the changes that the Federal Reserve has made to the discount window since 2020.

Traditionally, resorting to the Fed discount window was stigmatizing for the institution in need, since it meant that it was unable to obtain funding in the private market and its only option was to resort to the lender of last resort, that is, the central bank. The discount window is one of the few remaining vestiges of early central banking, epitomized by Walter Bagehot’s adage of “lending freely, at a penalty rate, against good collateral”.

On March 15, 2020, at the start of the pandemic, the Federal Reserve implemented two policy changes to destigmatize and make use of the discount window more attractive.

- First, the spread between the interest rate at the discount window and the upper target of the Fed Funds rate by the Federal Reserve was reduced, which softens the penalty for borrowing at the discount window compared to alternative sources of financing.

- Second, the maximum term of credits granted through the discount window is extended from one day to 90 days, renewable daily with the option to pay at any time, which makes these loans more flexible.

These changes are still in effect today and may be one of the reasons for the recent popularity of the discount window.

One of the common alternative financing methods for banks when they anticipate a more lasting need for short-term funds are the Federal Home Loan Banks or FHLBs. These banks, which are government-sponsored enterprises, or GSEs, are among the largest lenders of Fed Funds in the interbank market.

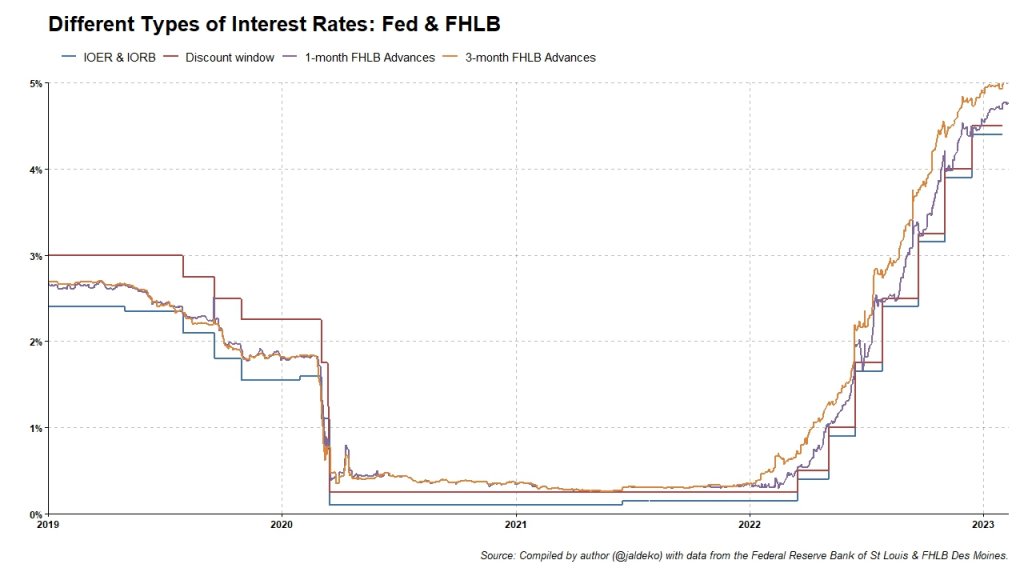

Therefore, it would be normal for commercial banks to have continued to depend on the FHLBs to meet their financing needs, before ever resorting to the discount window. However, as can be seen in the following graph, the interest rate of the term loans granted by FHLBs (called FHLB Advances) has been higher than the rate charged at the Federal Reserve discount window since 2020.

As this monetary policy tool allows for loans of up to 90 days, ever since the conditions of the discount window were modified, the banking sector’s need for term loans have been filled by the Fed’s discount window, to the detriment of FHLB Advances (1 to 3 months) in light of its higher cost. This is another reason that explains the increasing use of the discount window.

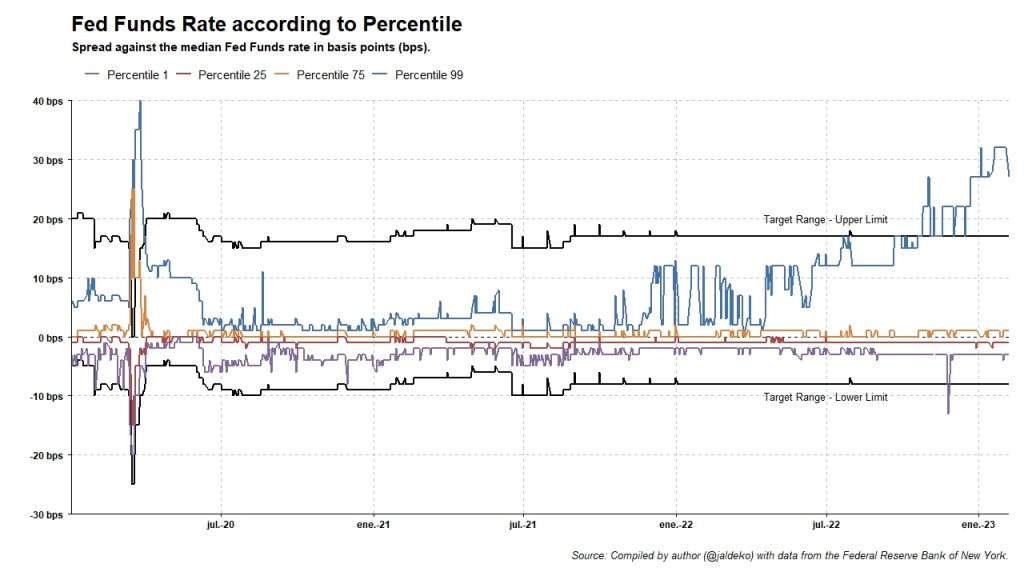

All this is reflected in the market interest rate of reserves. This rate, called the Effective Fed Funds Rate, or EFFR in short, is the volume-weighted median of all Fed Funds loans in the interbank market. Although the median remains flat relative to the interest rates set by the Federal Reserve, it can be seen how it has varied across different percentiles.

The chart above shows that the top 1% of loans are getting more expensive, which shows that there is at least a small part of the market that is facing problems in borrowing and obtaining reserves from the market.

Is There a Risk of a Financial Crisis in the U.S. Banking Sector?

For the moment, although access to financing has become considerably more expensive for some depository institutions, this has not yet had any influence on the median interest rate, so it is likely that, at least for now, it reflects localized distress in smaller banking institutions.

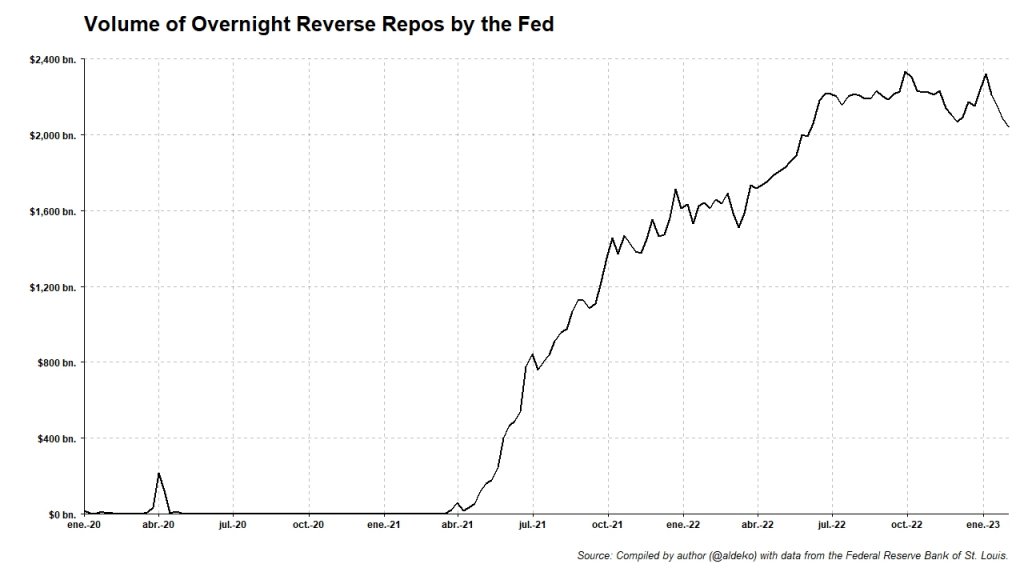

Also, as the first chart showed, the Fed’s Quantitative Tightening (QT) has reduced the amount of reserves in the system, but it has failed to reduce the amount of overnight reverse repos. This monetary policy tool, the use of overnight reverse repos, is a mechanism that the Federal Reserve can use to absorb excess liquidity in the money market. In other words, for practical purposes, it functions as a reserve fund in which financial institutions can deposit excess liquidity and receive interest in exchange.

The amount of liquidity stashed away in the form of reverse repos is at all-time highs. This means that, in the event that bank reserves are reduced aggressively by the Fed and the money market tightens further, the banking sector could encourage institutions to withdraw their liquidity from the Federal Reserve and deposit it in the money market (for example, higher yielding deposits) to increase the amount of reserves at the cost of reducing the amount of overnight reverse repos with the Fed.

Although it does not appear to be something worrisome for the moment, it will be wise to keep an eye on what is happening in the money market in case it could deliver any unwanted surprise in the (near) future.

Legal disclaimer: the analysis contained in this article is the exclusive work of its author, the assertions made are not necessarily shared nor are they the official position of the Francisco Marroquín University.

—

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Jon Aldekoa

Jon Aldekoa Vázquez studies Business Administration and Finance and is currently finishing a degree in Physics. He is a member of the Juan de Mariana Institute (Spain) and also collaborates with Students for Liberty and the Friday Club.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions