Sri Lanka’s Environmental Suicide

Currently, 1.6 percent of the world’s agricultural area is dedicated to organic farming.[1]

Although this form of agriculture has grown in recent years, it is still a niche market in which there is not high demand for products at the prices that this industry can offer, at least not yet.

Despite this, a small South Asian country, Sri Lanka, had the courage to initiate a massive organic farming program throughout the country. It is the first country to shift its entire agricultural sector to organic agriculture.

This article analyzes the Sri Lankan experiment. Does organic farming work, as environmentalists claim, or does the use of preindustrial technologies create problems with agricultural yield, as critics claim?

Let us begin by analyzing the political project that gave rise to this bold initiative.

Victory at the Polls in 2019 and the Beginning of the Organic-Farming Adventure

In Sri Lanka’s presidential campaign in 2019, the country’s president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, promised to transition the country to organic agriculture within a decade.

However, it seems the president was in a bit of a hurry. As early as May 2021, the government imposed a ban on the import and use of synthetic fertilizers and non-natural pesticides, as the principles of organic farming demand. This effectively forced the more than two million farmers in the country to adopt organic farming. In other words, the government did not merely promote to organic agriculture but forced one.

The Ministry of Agriculture expected yields to remain near pre-organic levels. The results came as a huge surprise to members of the government.

The Latest Fad in Technocracy Reached the Government in 2019

The transition to organic agriculture in Sri Lanka did not simply emerge; rather, it was actively promoted by a civil society movement called Viyathmaga. Members of this movement proclaim themselves to be technocrats with spiritual principles. Part of its mission is to “mobilize the expertise and knowledge of the members of this forum in innovating and developing strategies and policies which would influence the decision making of the government in power, for the greater good of the society.”

The movement’s mission statement makes constant reference to academics, technicians, professionals, and the need to implement public policy in a technical manner to improve the welfare of the population.

Members of this movement presented a program comprising ten major public policy proposals with an eye toward the 2019 elections. This program—named People-Centered Economy—included the bulk of organic-farming principles and the suggestion that organic farming should be fully adopted within ten years.

When the current president of Sri Lanka won election in 2019, he made several members of the movement ministers. The new minister of agriculture is one of the self-styled technocrats. Thus, it seemed that the dream of large-scale organic farming was going to become a reality; Sri Lanka would lead the world’s green movement by implementing organic farming at a large scale.

The new government’s commitment to organic agriculture was not going to end with the appointment of a minister. Sri Lanka created numerous advisory committees to implement policies that would allow the country to reap the rewards of organic and environmentally sustainable agriculture.

What Was Sri Lankan Agriculture Like before the Technocrats Came to Power?

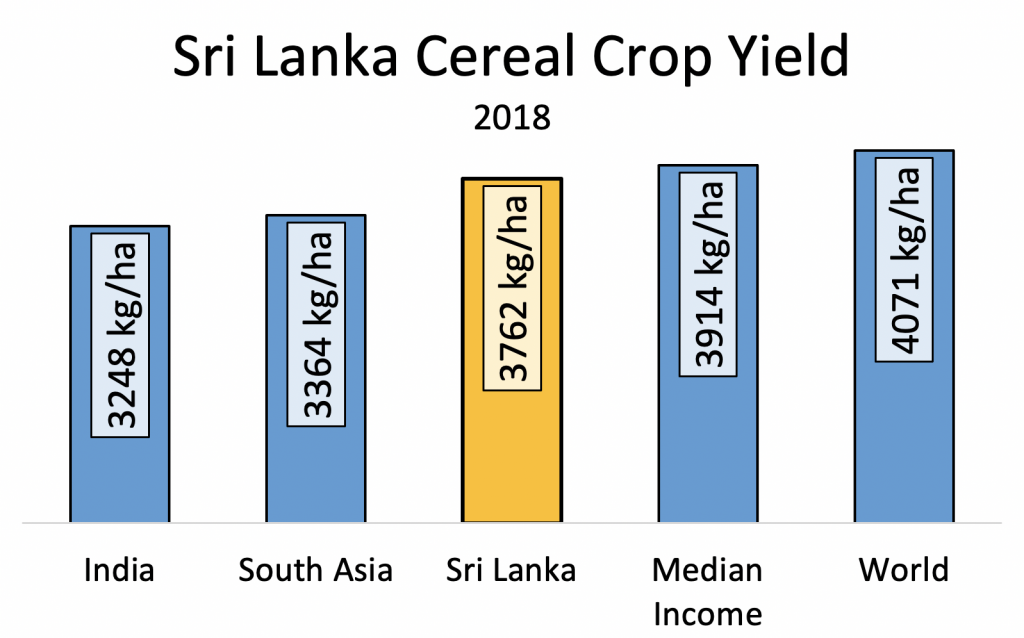

Exactly what were the self-styled technocrats trying to fix? Was Sri Lankan agriculture suffering from problems? Productivity per hectare of land in Sri Lanka before the policy change was higher than that of surrounding countries in South Asia and slightly lower than that of middle-income countries (of which Sri Lanka is one). In other words, there were certainly problems in the agricultural sector in Sri Lanka, but it does not seem that there was an urgent problem that required a 180-degree turn in public policy.

Source: World Bank

The Technocrats’ Organic-Farming Policy

Although there did not seem to be any major problems in the agricultural sector, the self-styled technocrats who had just entered government wanted to overhaul Sri Lanka’s agricultural policy from top to bottom. They intended to implement their organic farming program as part of their ambitious agenda.

Among the agricultural policies to be implemented in order to reach the desired large-scale organic agricultural production were the following:

- The elimination of synthetic fertilizers

- The production of biofertilizer in the country’s forests and wetlands

- The creation of more than two million small-scale vegetable gardens in small homes to provide food for the country

All of this may sound wonderful to the average cosmopolitan in a Western city, but it looks suspiciously like a preindustrial form of food production (preindustrial agriculture was so unproductive that it required approximately 90 percent of the population to be employed in farming). Currently, 25 percent of Sri Lanka’s population is employed in agriculture (a relatively high number for a developing country). Despite this, the technocratic movement’s supposed experts and academics estimated that agricultural productivity would remain at similar levels to those of previous years.

What Could Be Expected from a Ban on Synthetic Fertilizers?

Given the available evidence, what results could be expected from the Sri Lankan experiment?

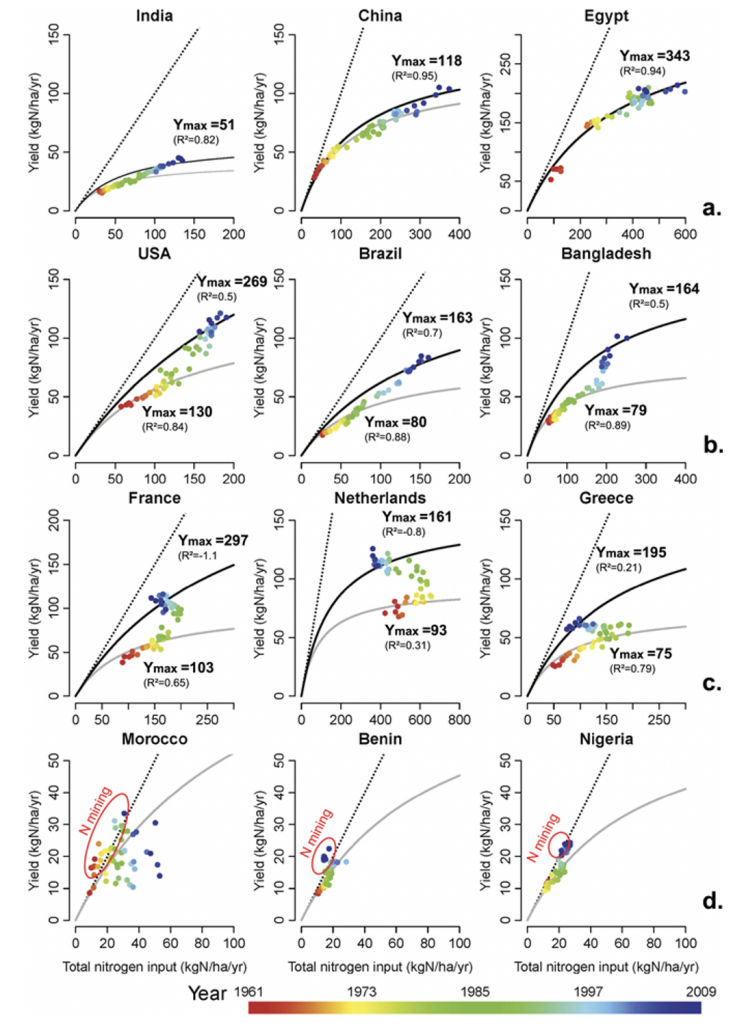

As a general rule, applying more fertilizer means higher crop yields. Although the application of fertilizer has a different impact in each country (and other key variables also explain agricultural productivity, such as the type of crop, the irrigation system, and the quantity and quality of farming equipment), it increases agricultural productivity. As can be seen in the graph below, fertilizer’s effect on agricultural productivity is positive but diminishing (economists call this diminishing marginal returns, and this is what can be expected when increasing the amount of any variable productive input).

Source: Lassaletta, Billen, Grizzetti, Anglade and Garnier (2014)

In very long-term studies, between 30 and 50 percent of agricultural yields can be attributed to the use of inorganic fertilizers.

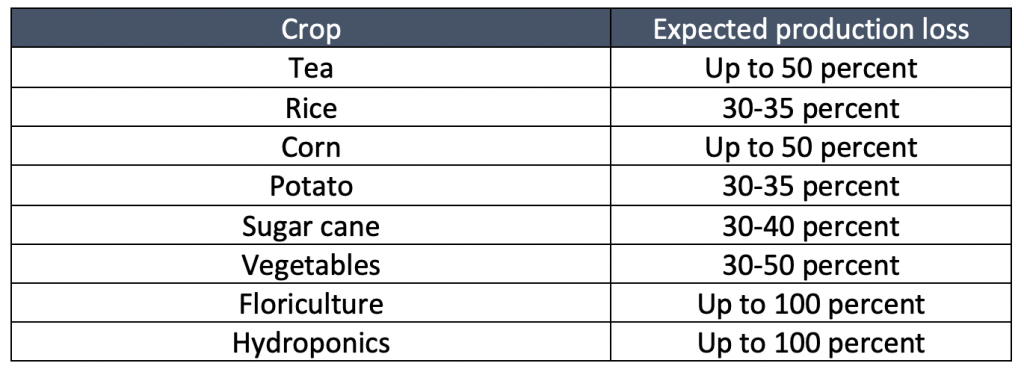

Some of the country’s scientists and agricultural specialists wrote a letter to their president warning about the harmful effects that the ban on fertilizer imports would have. They estimated that key crops, such as rice and tea, would experience production declines of 30–35 percent and up to 50 percent, respectively. Similar figures can be seen in the following table.

Table 1: Expected Loss of Agricultural Production by Banning Artificial Fertilizer and Pesticides (Sri Lanka)

Source: Inorganic fertiliser ban could harm production with major implications | Daily FT

Therefore, there seems to be little doubt that fertilizer use increases agricultural productivity.

In view of the evidence, then, the ban on synthetic fertilizer imports might have been expected to cause Sri Lanka’s agricultural productivity to plummet.

What Was the Outcome of the Massive Experiment?

Unsurprisingly, the drop in agricultural production has been dramatic. However, the situation is more complicated than some preliminary studies suggested. Some studies analyzed Sri Lanka’s total agricultural production in 2021, but the shift to organic agriculture began only in May 2021 with the ban on the import of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Therefore, it did not affect all crops planted in 2021 and will continue to affect some planted after the measure was lifted in November 2021. We will attempt to isolate the effect of organic farming on two crucial crops, rice and tea, and a traditional crop, rubber.

Rice

Rice is probably the most important crop in Sri Lanka, as it is the staple food for millions of Sri Lankans.

There are two rice harvests per year in Sri Lanka. The planting period for the first harvest begins in April, a month before the ban on imports of fertilizer and pesticides was introduced, so it is highly likely that farmers already had the necessary supplies of these products for the harvest in progress. The planting period for the second rice harvest begins in October, just before the fertilizer import ban was lifted in November, too late for farmers to obtain the fertilizers and pesticides needed for planting.

Based on preliminary and unofficial figures, the yield of the second rice crop in Sri Lanka fell by as much as 45 percent, with some estimates in some provinces pointing to as high as a 50 percent drop, even though weather conditions were very favorable at the time of planting, as reported by FAO.

Tea

Tea is Sri Lanka’s main export product, accounting for almost 10 percent of the country’s net exports. It is Sri Lanka’s third-largest source of foreign exchange after remittances and tourism. A drop in tea production and exports would significantly damage an economy that was already suffering from foreign currency shortages due to a drop in tourism in 2019 and 2020.[2]

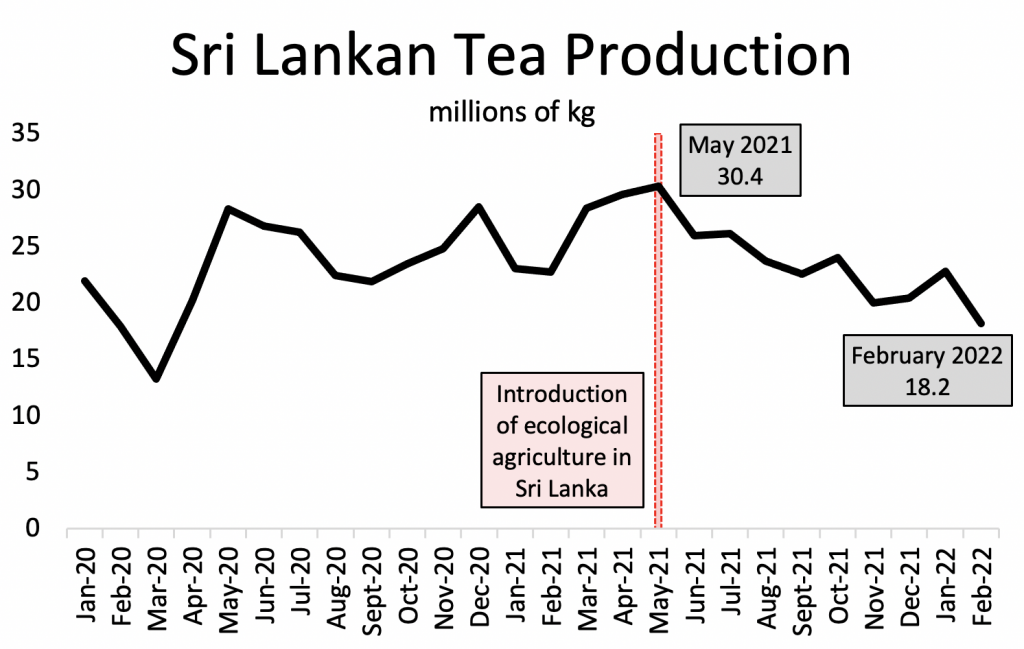

More accurate data are available for Sri Lanka’s tea production. In February 2022, 20 percent less tea was being produced than in February 2021. As can be seen in the graph, the drop in production has been sustained (although not as dramatic as with rice, mainly because the maturation period is much longer for tea).

Source: Forbes & Walker

Rubber

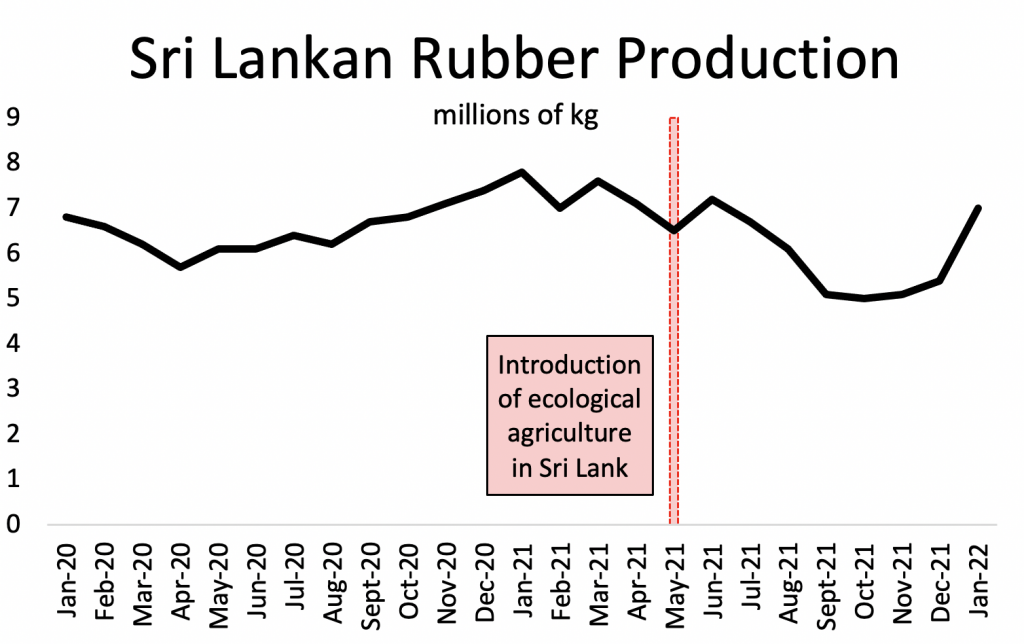

Another traditional Sri Lankan crop is rubber. A notable drop can be seen here as well. In the first half of 2021, rubber production had increased by 15.2 percent compared to 2020, whereas in the second half of the year, when the ban on fertilizer imports came into effect, production fell by 17.7 percent compared to 2020.

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Estimates for the entire year suggest that rubber production did not decrease in 2021, but this is liable to be misinterpreted. During the period of organic farming, the production of this agricultural commodity plummeted.

As economic theory predicts, a black market for fertilizers has emerged in Sri Lanka in the face of the ban on their use and importation.

Therefore, it seems clear that Sri Lanka has just committed economic suicide prompted by the recommendations of alleged experts who were nothing more than environmentalists.

However, it appears that, in addition to heeding the misguided environmentalists, the country had other reasons for moving toward organic farming.

Shady Reasons behind the Fertilizer Import Ban

Sri Lanka had a decades-long policy of subsidizing fertilizer for farmers. The subsidy accounted for between 48 and 88 percent of farmers’ fertilizer expenditures (depending on the type of crop). In 2020 the subsidy expenditure was 53.6 percent of total government spending in the agricultural sector.

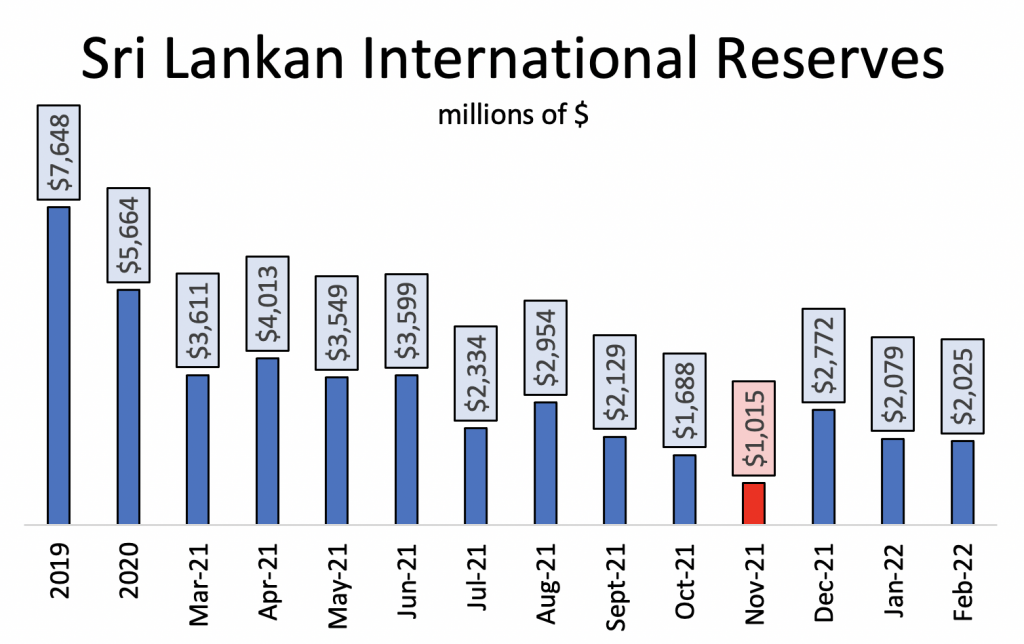

Sri Lanka’s economy suffered greatly during the 2020 recession because one of its main industries and sources of foreign exchange is tourism. Sri Lanka has not yet recovered from this huge blow.

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka; World Bank; Knoema

Faced with such a blow, it is quite possible that the government desired to accelerate the transition to organic farming in order to avoid financing the cost of fertilizers, as the money was not available. In other words, the government probably wanted to kill two birds with one stone: it avoided an expense for which it did not have the resources, and it implemented the long-awaited policy promoted by the self-proclaimed technocrats.

Thus, rather curiously, Sri Lanka went from subsidizing fertilizer for decades to banning them completely in May 2021.

The huge drop in agricultural production has led to a need for emergency imports of huge quantities of food to avoid a famine, which has further drained Sri Lanka’s international reserves, as shown in the graph. In addition, the drop in tea production and exports has also caused problems in the balance of payments and the almost-complete depletion of international reserves.

Conclusion

When the Presidential Task Force for Green Agriculture in Sri Lanka (a committee on the implementation of the public policy on organic farming) was established, it declared “emphatically” that “action would be initiated to build a developed agricultural economy and to create an opportunity for the local and international consumer to obtain toxin-free agricultural products within the next decade as well as to introduce eco-friendly crops.”

The grandiosity of these words is at odds with the results of the public policy. In light of what happened in Sri Lanka, and to avoid further disasters and possibly widespread hunger, it is a good idea to exclude environmentalists from public policy decisions of significance. The best thing to do is to leave environmentalists to their natural activities and environment: giving lectures on morality on social media.

Legal notice: the analysis contained in this article is the exclusive work of its author, the assertions made are not necessarily shared nor are they the official position of the Francisco Marroquín University.

–

Notes

[1] Click here to see the source

[2] The decrease in tourism was due to a series of terrorist attacks in 2019 and the pandemic in 2020.

Sri Lanka’s Organic Farming Experiment Went Catastrophically Wrong (foreignpolicy.com)

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Daniel Fernández

Daniel Fernández is the founder of UFM Market Trends and professor of economics at the Francisco Marroquín University. He holds a PhD in Applied Economics at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid and was also a fellow at the Mises Institute. He holds a master in Austrian Economics the Rey Juan Carlos University and a master in Applied Economics from the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions