The Astonishing Differences Between Spain’s 1993 and 2007 Crises

It seems that the echoes of Spain’s Great Recession will never end. Despite the country’s strong growth for at least two years, the general feeling seems to be that of a country consumed by the resonance of its own misfortune.

In the same way that economic growth is a fact far beyond the perceptions of the average Spaniard, the shift towards a new productive model is a reality that surpasses the constant misrepresentations of politicians and economists. Many of these politicians and economists are simply trying to turn the suffering of others—perceived or real—into political gains.

Changing Spain’s Productive Model

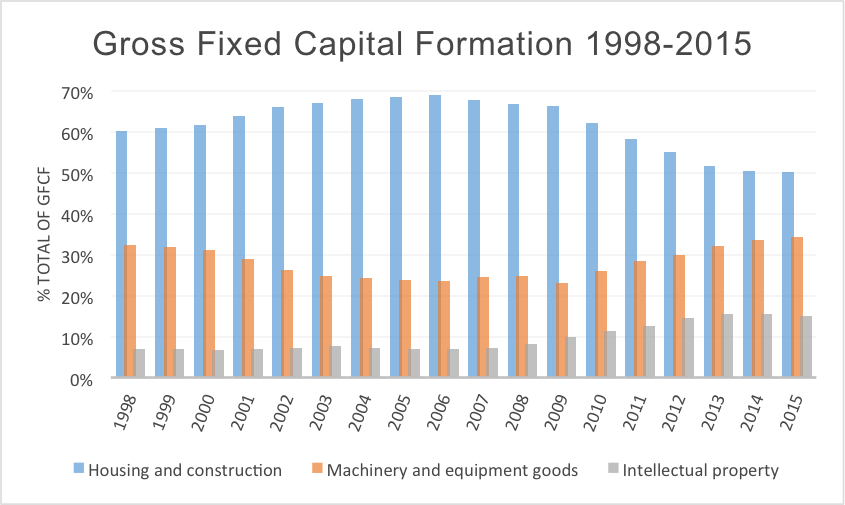

For the first time since 2007, in 2015 gross fixed capital formation—investment in future productive capacity—increased with respect to the previous year. Even more important than the total amount of investment in fixed capital is its composition, given that it can show future productive patterns. As seen in the following graph, fixed capital formation has suffered a great change since the peak of the real estate bubble.

Source: INE Graph: Gross Fixed Capital Formation 1998-2015. Side: % total of GFCF. Blue: housing and construction. Orange: Machinery and equipment goods. Gray: Intellectual property.

With help from the data from the Spanish Statistical Office, we can see how the gross fixed capital formation in housing managed to encompass nearly 70% of new investment in 2006. This figure was 50% in 2015. Contrarily, investment in machinery and capital goods fell to 23.6% in 2016; when in 2015 it exceeded 34%. Intellectual property, or in other words the result of R&D—a subject pending of the Spanish economy—increased from a modest 7% in 2006 to 15% in 2015.

If we examine the data of fixed capital formation provided by Eurostat, we see Spain’s productive sector being transformed. Construction goes from representing almost 15% of fixed capital investments to 6.7% in 2014. The energy sector is worth noting, as investment rises from 2.3% to a total of 9.0%. Also interesting to observe is the evolution of investment in professional, scientific, and technical activities, which increased from 1.7% to 4.5%.

The graph shows that construction in is deflating and other sectors are taking over. Worth noting are the increases in scientific activities and the energy sector.

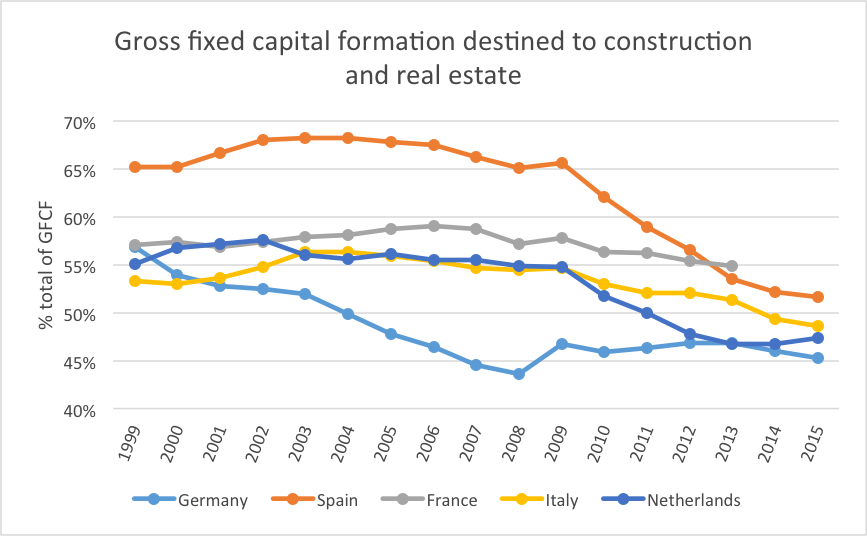

In the following graph, we can see how the construction and real estate sector of the Spanish economy used to surpass the same figure for other European countries. Since 2009, however, these figures have dropped dramatically, finding themselves in a position similar to their fellow European partners in 2015.

Source: Eurostat. Graph: gross fixed capital formation destined to construction and real estate. Side: % total of GFCF. Countries from left to right: Germany, Spain, France, Italy, Netherlands.

Indeed, it seems that Spain has been able to make the desired change of its production model.

The Euro: Unnecessary Straightjacket or Catalyst for Change in the Productive Structure?

However, it remains to be seen whether belonging to the monetary union has helped change the composition of the productive sector or whether this is something that would have happened regardless (and could have avoided the adjustment policies and containment of labor costs).

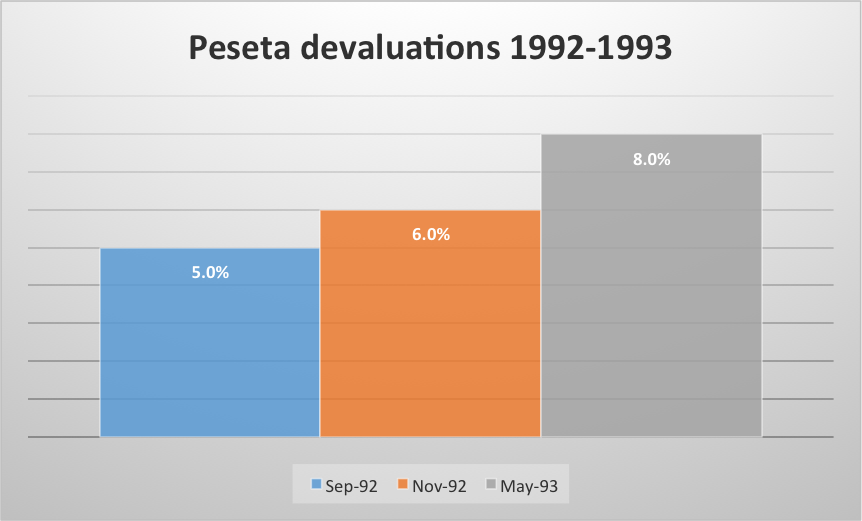

To this end, we will analyze the last crisis that Spain underwent before 2007. The 1992-93 crisis was much shorter and was ended by devaluating the peseta—Spain’s currency from 1896 to 2002—3 times in less than a year. In this context, the so-called internal devaluation—internal price adjustments and nominal wage devaluation—was avoided.

The devaluation of the peseta seems to have avoided harsh the adjustment measures seen since 2007. The devaluation made Spanish workers relatively cheaper—and poorer—than those of other countries and competitiveness in international markets rose, there was no need for a decrease in nominal wages.

In this sense, the devaluation seems to be a cleaner and faster way out of an economic crisis; therefore, the Euro would be an unnecessary “straightjacket.” Yet, there are two big problems with this approach.

- The devaluation leads to increases in competitiveness through the monetary path, not by increasing productivity.

Companies are not pressured to innovate the products or services they offer. Increases in competitiveness through monetary policy tend to be temporary and undermine productivity. This can help explain the low increase of Spanish productivity during the 90s and 00s.

- Devaluation avoids changes in the productive structure.

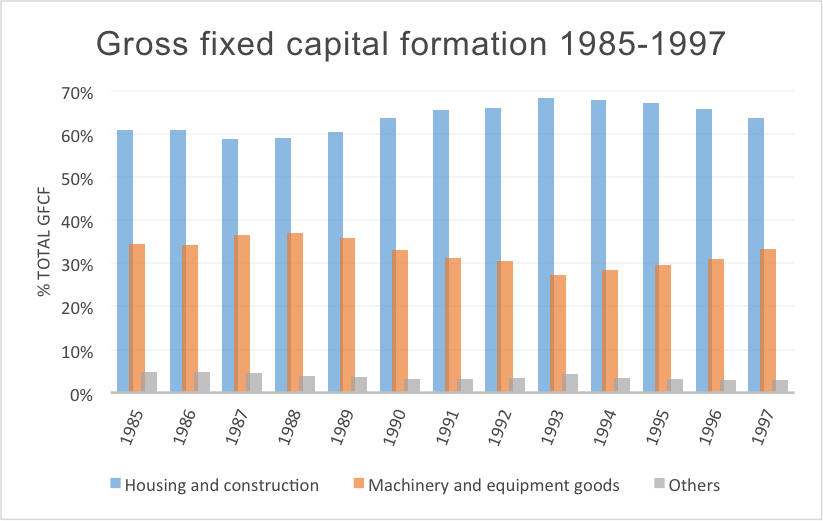

If Spanish companies find a market for their products abroad by monetary means (devaluations), the factors of production do not change hands. Business losses turn into profits due to the devaluation. When there is no pressure to change the productive structure, it remains the same. Capital and workers remain stuck in sectors with little value added, which would need further devaluations in the future to continue operating.

Source: INE. Graph: Gross fixed capital formation 1985-1997. Side: % total GFCF. Blue: housing and construction. . Orange: Machinery and equipment goods. Gray: Intellectual property.

Thus, we see how solving the crisis through monetary means leaves a fixed capital formation similar to the one that existed before it, focused on housing and construction.

This could also partially explain the low increase of Spanish productivity in the 1990s and 00s. The productive structure was never under the pressure to change in an economic crisis.

Conclusion

The 2007 crisis, with all of its depth, has served to change the outdated Spanish productive structure. Construction and real estate are losing strength. Emerging sectors include scientific and technical activities as well as the energy sector.

The comparison between the 1992-93 crisis and the 2007 crisis—the last two Spanish crises—shows that the best mechanism to make changes in the productive structure in internal devaluation rather than the devaluation of currency.

An economic crisis is nothing more than a confirmation that the qualitative composition of supply is no longer aligned with the wishes of the consumer and must be changed. From this perspective, the Spanish crisis of 1992-93 was falsely ended and helped make the 2007 crisis much more severe.

Spain’s membership of the Eurozone has helped changed the productive structure and avoid a devaluation.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Daniel Fernández

Daniel Fernández is the founder of UFM Market Trends and professor of economics at the Francisco Marroquín University. He holds a PhD in Applied Economics at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid and was also a fellow at the Mises Institute. He holds a master in Austrian Economics the Rey Juan Carlos University and a master in Applied Economics from the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions