Why Should Shadow Banking in China Concern Us?

The economic crisis of 2008 was, to a large extent, caused by the way in which resources were allocated within the economies of other countries. Depending on whom you ask, the causes and effects of the 2008 crisis vary, and discrepancies do exist. However, there is one common ground among many; that being shadow banking.

Shadow banking arises when banks respond to incentives generated as a result of laws and conditions placed on bankers by the Fed. Shadow banking happens when intermediaries not being regulated or supervised by laws, and other entities act as financial institutions without following financial regulations and guidelines. Because of the incentives that spawn from the regulations, these entities are put to use as receivers of funds and issue credit at higher risks than in the traditional banking system, thereby generating higher returns and making them more attractive.

Shadow banking began seeing leaps in growth and formality largely via Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV) and to some extent in Hedge Funds. These entities offer better returns as a result of the higher risk transactions that are conducted. The 2008 crisis was provoked by a credibility gap created by financial instruments used during transactions conducted by shadow banking entities. These instruments are called credit derivatives and examples include credit default swap (CDS) and asset backed securities (ABS). One such industry that utilized these financial instruments a great deal is that of real estate in the United States. It’s not that shadow banking is a bad thing, but it creates higher risk conditions that should only exists if an individual accepts it, and hence, also accepts the possible losses that come with it.

The most basic principle of microeconomics is that an individual prefers more to less. If we expand this idea to the financial markets, we can say that an individual prefers more returns to less. More returns, however, means higher risk. Since 2008, what has been happening in different world economies is that regulations have been being put into place in order to reduce risks and try to restore credibility within some of the most influential industries. For this reason, some regulatory agencies would buy investable instruments that they considered to be of higher risk thereby gradually correcting the market.

More legislation is being implemented to avoid the financial system having to incur all of the risks. In theory, however, this is not what should happen. In the face of this new legislation, the individual underestimates the real risks involved creating different kinds of bubbles and a concentration in the allocation of resources in investments that in fact are risky. These new regulations cloud the vision of the individual and any research he/she may have done.

China: A paradise eclipsed by regulations

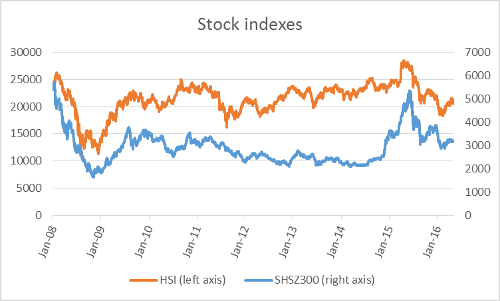

Since the crisis of 2008, a lot of pessimism has existed throughout the different economies of the world resulting in capital being moved around to different investments thus affecting the market in a number of different ways. China has been affected due to a larger concentration of capital flow that, to a certain extent, could be considered a bubble. We see this effect, after 2009, in how market capitalization was influenced by a significant influx of capital in the form of investments.

Little by little, Chinese regulatory agencies have imposed certain guidelines for operating in this sector. Many of these regulations have been laid out in our previous reports on China’s economy and its curbing of IPOs, its decisions made regarding gold and dollar reserves and, what some would consider, capital controls. Similarly, devaluation measures and quantitative easing (QE) are transforming the world of investing in China.

He who wishes to maximize his returns finds himself in a difficult situation. It’s already too late to take advantage of returns on fluctuations in supply and demand in the stock markets, and the other higher-risk investments are now being regulated. What arises now in China is the same as what arose in the United State a few years ago: shadow banking crops up as a way of seeking higher returns.

What is happening in China?

In the face of strong regulations, conditions in the market and distorted analyses, the individual looks to allocate his resources within entities that promise better returns at higher risks. We see evidence of this in two ways: the increase in Wealth Management Products (WPMs) reported by certain Chinese financial institutions (WPMs being the instruments utilized by unsupervised financial entities) and the increase in bad debt reported by financial entities that are supervised by the Chines government. According to data from the Wall Street Journal, these figures have risen rapidly from $390 million in January of 2015 to $1 trillion dollars in March of 2016.

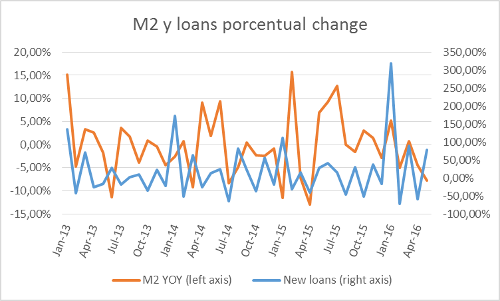

Furthermore, it is important to note the growth in loans coming from Chinese banks. These tend to fluctuate depending on market conditions. Rates on these new loans have been rising gradually throughout 2016 but M2 has been decreasing. This demonstrates how banks are incurring higher risks when lending even when, theoretically, less funds are available as M2 decreases.

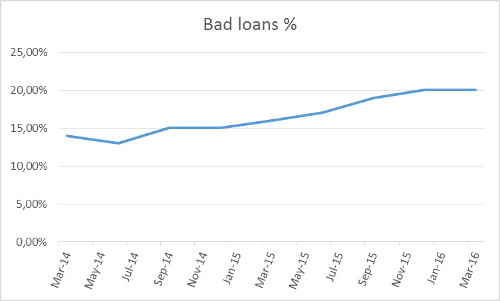

As previously mentioned, we all prefer more returns to less. Returns in the private banking industry come from loans and the spread generated between short-term and long-term interest rates. Nevertheless, with higher returns come large risks, and this is illustrated in the following graph entitled Bad Loans. These bad loans indicate how the economy may be presenting problems, because it shows that borrowers have been unable to pay off their debts. It also shows how banks take on more risk, because their incentives are distorted. This is what is meant when discussing how regulations distort how an individual measures and accepts risks.

In less than two years, bad loans have increased by 5%. In Market Trends, we highlight this fact because it indicates current conditions in the market. It becomes more and more apparent that the analysis discussed in a previous Market Trends article about medium-term expectations in China is worrisome. While decisions made by supervising financial agencies continue to distort how risks are measured, the risk of a 2008-style crisis becomes more real. We will delve into this topic in more depth in our future reports on the economic outlook of China.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Roberto Morales Chang

Roberto Morales Chang has a bachelor’s degree (BA) in Economics with Finance specialization, Cum laude, from Universidad Francisco Marroquin.

He’s an assistant professor at UFM’s Henry Hazlitt Center for the courses Economic Process I and Economics Process II.

Some of his areas of interest but not limited to are monetary theory, financial economics, history of economic thought, economic history and entrepreneurship.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Bad loans may have increased by only 5% of total loans, but by almost 35% of bad loans.

The second figure give a more realistic idea of the problem.