Public Debt: The Great Recession (2007) versus the Great Lockdown (2020)

The 2020 recession, which many countries are still going through, now has an “official” name: the Great Lockdown. In economic terms, the public sector’s response in practically all countries has been very swift and bold (which is not necessarily a good thing).[1] This has caused the global public debt to skyrocket as never before. As a result, now more than ever, it is necessary to emphasize the dangers of public debt.

In this article, we will highlight the contrasts between this recession and the previous one (the Great Recession of 2007) to analyze the public-debt problem the world is facing. In a second article, we will analyze the economic dangers of excessive public debt.

The Public Sector Entered This Recession in a Much Weaker Position than in 2007

During the economic expansion that ended in 2020, the public sector in most countries was almost totally complacent about deficit spending. Levels of public debt shot up practically everywhere. So public debt in the Great Lockdown was considerably greater than in the Great Recession in all of the major regions of the world.

Of the seven major world economies (G7), only Germany bore less public debt at the beginning of 2020 than it did at the beginning of 2007.

The Debt Resulting from This Recession Is Unparalleled

The public sector has responded to the Great Lockdown recession with a fiscal expansion unparalleled in history. In 2009, the year with the largest fiscal deficit during the previous recession, global public debt increased by 10.5 percent of GDP. In 2020, global public debt increased by 18.7 percent of GDP.[2] Across all regions we can see a huge contrast between the current recession and the Great Recession. Even countries in Latin America, which ran only moderate deficits in the previous recession, have significantly increased their debt as a response to the Great Lockdown of 2020.

Advanced economies accumulated 50 percent more debt in 2020 than in the ten previous years combined, an unprecedented figure in peacetime.

The Twenty-First Century Is the Century of Public Debt (and Potential Default)

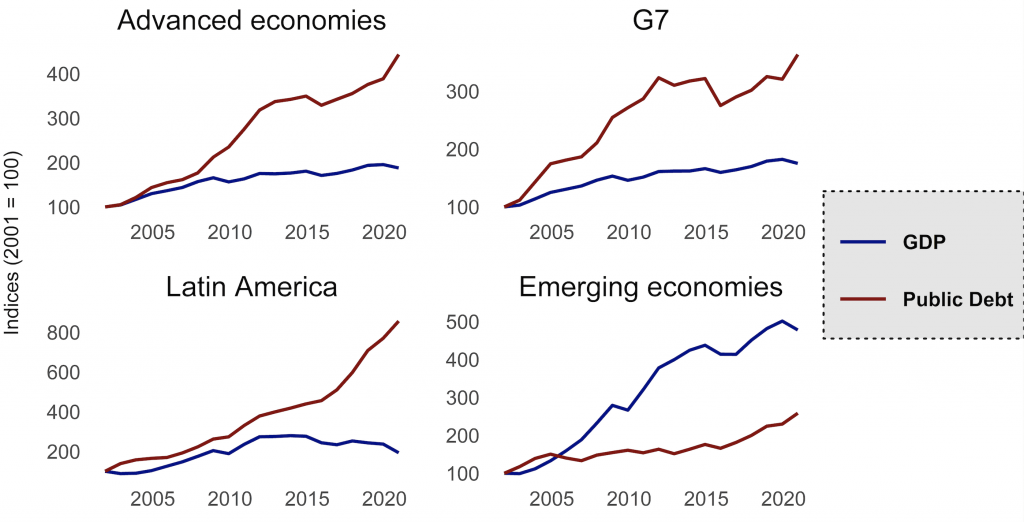

The amount of public debt accumulated since the beginning of the twenty-first century would have left the most insightful commentators of a century ago at a loss for words. However, the wealth and income attained this century would have also left even the most optimistic of our great-great-grandparents speechless. Accordingly, while it might seem that public debt is growing uncontrollably, since wealth is also growing exponentially one could conclude that the debt does not pose a problem because we are generating the resources with which to pay down the debt. However, in most parts of the world, public debt has grown faster than the economy. Only in emerging markets is the economy growing more rapidly than public debt is.

Chart 4 GDP Growth and Increase in Debt (2001–20)

Source: Prepared by the author with data from the International Monetary Fund. Debt and GDP in 2001 dollars were used to calculate the indices (as it is the most appropriate way to compare ability to pay).

In the most advanced economies, the public debt was 4.5 times larger in 2020 than 2001. It is expected to multiply sixfold through 2025.[3] Meanwhile, GDP was only 1.9 times larger in 2020 than 2001, and it is expected to be 2.4 times larger in 2025 than 2001. The advanced economies are on a trajectory of public-debt accumulation that is unsustainable in the medium term.

The good news is that emerging economies, as well as sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and ASEAN-5,[4] are increasing their debt at rates significantly lower than their economic growth rates. Unfortunately, advanced economies’ enormous accumulation of debt has not been offset by the reduction in debt (relative to the size of the economy) in emerging markets.[5]

Conclusion

In this first article on the development of public debt since the start of the COVID pandemic, we have demonstrated that the accumulation of public debt may be reaching a point of no return for the world’s major economies. The debt accumulation was already unsustainable prior to 2020, but the Great Lockdown has triggered an explosive increase.

The second article will analyze the problems this excess public debt will cause.

Legal notice: the analysis contained in this article is the exclusive work of its author, the assertions made are not necessarily shared nor are they the official position of the Francisco Marroquín University.

–

Notes

[1] A swift and decisive response to stop the spread of the virus while avoiding monetary and fiscal expansions would have been preferable.

[3] International Monetary Fund estimates.

[4] The last two regions are not included in chart 4.

[5] In 2001, advanced economies made up 79 percent of global GDP, but in 2020, this figure fell to 59 percent.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Daniel Fernández

Daniel Fernández is the founder of UFM Market Trends and professor of economics at the Francisco Marroquín University. He holds a PhD in Applied Economics at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid and was also a fellow at the Mises Institute. He holds a master in Austrian Economics the Rey Juan Carlos University and a master in Applied Economics from the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions