Everything you need to know about negative interest rates

By Daniel Fernández April 11, 2016

Translated from Spanish by Robert Goss

Ever since the onset of the 2008 recession, the most important central banks of the world strung up their imaginative sides and came up with a series of steps and measures to not only halt the effects of the devastating liquidity crisis but also devise a plan to boost the economy during its aftermath.

One of the less conventional monetary policy measures being taken is the use of negative interest rates. The justification for such a measure is the hope that it will prompt a credit boost in the capital market. With this boost in credit, it is hoped that the economy will follow suit. Let’s take a minute to respond to some of the most common questions regarding negative interest rates.

Are all interest rates negative interest rates?

No, central banks only indirectly control short-term interest rates and with that, hope to influence long-term decisions.

Central Banks specifically establish two separate interest rates, not only one.

- They fix the interest rate that is charged to banks that are in need of reserves.

- They fix the interest rate that is paid to banks that have an excess of reserves.

Normally, it is this last kind (the rate on reserves kept in central banks by private banks) on which various central banks have placed a negative interest rate.

Why were central banks paying interest to private banks to hold its reserves?

Until 2008, the main central banks were paying no interest on reserves to private banks for keeping these reserves in the Central Bank.

Ever since the end of 2008, central banks have created an enormous amount of reserves with the purpose of preventing a wave of default payments as a result of the liquidity crisis. In order to avoid risking that private banks use these reserves as a basis for sporadically issuing new credit, they instead decided to pay interest on them.

This interest rate becomes the minimum interest rate among all banks. No bank would logically issue reserves at a lower interest rate to other private banks when they can simply do so with the Central Bank at no risk and at a higher rate.

Before 2008, monetary policy was to regulate the amount of reserves in the system by means of open market activity (the purchase and sale of public debt securities) in order to affect its quantity and thus its price. After 2008, the large amount of reserves created makes it so that these proceedings no longer make sense and the rates are regulated by these same reserve payments to the private banks.

Why do private banks keep so many reserves in the central bank if they receive no interest for them?

There is really very little that private banks can do to modify the amount of reserves that are deposited into the central bank. There are only two entities in the economic world that are permitted to hold an account in the central bank; the State and private banks.

When the central bank decides to increase the amount of reserves (for example: by means of Quantitative Easing), along with that increase comes a rise in total reserves in the system. This prompts the following two side effects:

- A drop in interbank interest rates

Banks offer loans to each other at much lower rates as a result of a rise in reserves. When liquidity exists, the cost of it drops or disappears entirely.

- A drop in interest rates on sovereign bonds

Banks also dispose of their reserve excess and place them with another entity that has access to accounts in the central bank, the State. This is the only way in which reserves leave the banking sector.

Would it make sense for the central bank to switch from paying rates to banks for holding reserves to charging them for the same service?

All central banks look to make it so that the opportunity cost for holding reserves in constantly less for the banking sector. Their goal is to have credit extended which in turn makes it cheaper to hold the necessary reserves.

Nevertheless, the current credit problem isn’t as much in supply as it is in demand. One of the main complaints during the Great Depression was that there was no effective credit demand. No credit is extended if no borrower exists and no borrowers exist if there is a lack of solvency. When economic circumstances are unfavorable, the last thing entities want is to indebt themselves further, and no matter how accessible and inexpensive they are offered this credit, it is completely normal for debt to remain the same.

When central banks charge to hold reserves for private banks, what they are really doing is pressuring the banks by imposing losses on a part of their assets. The reason for doing this is to compensate for these losses by means of creating new credit for the real sector of the economy. Negative interest rates, far from being a blessing for private banks, are an extra cost that the central banks impose in order to provoke private banks to lend more freely. From this point of view, and in light of the lack of financially sound creditors, taking these measures is peculiar, because a foundation for the creation of low quality credit is being created that will cause problems in the future.

Why do States utilize negative interest rates, as well?

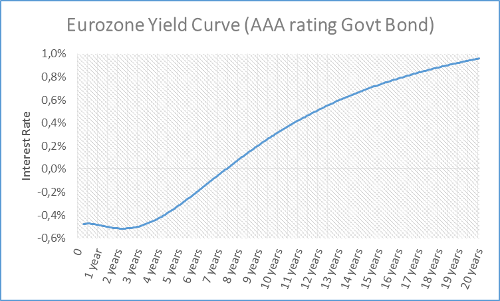

We currently see that the triple A government bonds interest rate curve in the Eurozone is in the negatives for all securities with a duration of less than 7 years 5 months.

Several answers exist as to why the use of Negative Interest Rates.

- The first reason we have already made mention. An excess in Central Bank reserves together with negative interest rates makes it so that lending to the State is the only way that the banking sector can become exempt from paying for these reserves.

- The Eurozone presently finds itself in the process of implementing Basilea III. Basilea III establishes stricter norms for capital and liquidity. The catch? Public debt is not considered an asset that follows capital or liquidity requirements. Henceforth, there is an additional demand for public bonds in order to comply with bank regulations, without putting much importance on having to pay more than what is earned on performance.

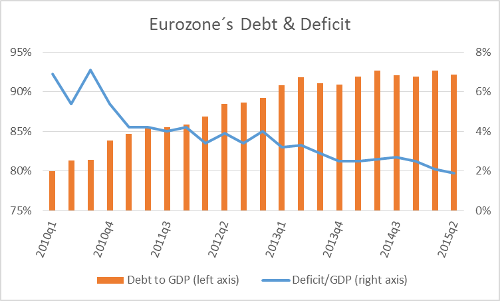

- Fiscal Consolidation. Lastly, European States exist in an aggregate form which reduces its deficits. This causes a rise in the scarcity of market securities.

If we combine these three explanations, we encounter an additional demand and a constraint on supply. This situation certainly does not conform with an open market. Negative interest rates are an obvious reaction to the implementation of unconventional monetary policies and the implementation of a bank regulation that unjustly benefits government debt over other kinds of assets.

What effects will negative interest rates have on the economy?

There are three possibilities.

- What Central Bank hopes for: Private banks will extend more credit to the real economy in order to compensate for losses inflicted upon them by the Central Bank.

This scenario is appropriate only for the short term and problematic for the middle and long term. Simply stated, credit standards are undercut in order to increase short-term returns. This additional credit and the added demand generated tend to create economic growth in the short-term at a cost of a rise in other imbalances in the long-term.

For the time being, no banks have opted for this route. The slight increase in credit available to families and businesses balance out with a lesser credit to the government (which slowly ends in fiscal consolidation).

- Banks pass the bill to the depositor.

The fee imposed on private banks by the Central Bank can be passed on to the depositor, at least partially. If private banks are reluctant to extend new credit to borrowers with not so perfect credit, this is the option that banks will go for. As of yet, no banks have begun to apply this option.

This can be a risky measure in the sense that it may provide a lack of incentive to other entities for keeping balances paid in full. This is the reverse of inflation, but with similar effects. If an entity prefers to keep its liquid assets, it must give up its store of value (negative interest eats away at capital) or if the entity prefers store of value, it must give up its liquidity (for example – the acquisition of real state).

- Private banks bear the brunt of the cost of this measure.

This is what is currently happening. The profitability of the European banking sector have experienced large setbacks recently even though no aggravation to credit portfolios has been seen. The reasons for this are a rise in negative interest rates and a rise in Europe quantitative easing that does nothing more than increase the amount of reserves that banks owe and pay interest on which we have seen cannot be prevented.

It is unlikely that banks will remain in this situation, at least if they want to prevent seeing a decrease on returns.

How high and to what extent can negative interest rates get?

As long as cash continues to be accessible at banks, the answer is clear. The cost of keeping cash on hand and out of the banking sector is of the least concern. Entities can rent a safety deposit box and deposit actual currency. A number of Swiss investment funds reached this extreme when the Swiss Franc’s exchange rate against the Euro lost its stability and Swiss interest rates suddenly dropped drastically.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Daniel Fernández

Daniel Fernández is the founder of UFM Market Trends and professor of economics at the Francisco Marroquín University. He holds a PhD in Applied Economics at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid and was also a fellow at the Mises Institute. He holds a master in Austrian Economics the Rey Juan Carlos University and a master in Applied Economics from the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions