Why Didn’t the Depreciation of the Yen Help Exporters?

Abenomics is the formula the Japanese government implemented to try to achieve a 2% inflation, improve the performance of the economy, and reactivate its exports—it was a new monetary policy, fiscal policy, and structural reform. These measures were implemented by Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2012 in order to revive the economy. Later on, this program would become known as Abenomics.

What did this monetary stimulus consist of? It is an aggressive policy of quantitative easing; in other words, it is consists of nothing more than a high increase of the monetary base. Following this line, the Bank of Japan began to increase the monetary base, injecting between ¥60 and ¥70 billion a year. In 2014, the monetary injection increased to ¥80 billion.

Before the stimulus package, the monetary base was 25% of GDP; by 2015 the monetary base increased to 57% of GDP—a brutal monetary injection. The following graph shows the annual growth rate of the Japan’s monetary base.

An Expensive Yen Is to Blame, Right?

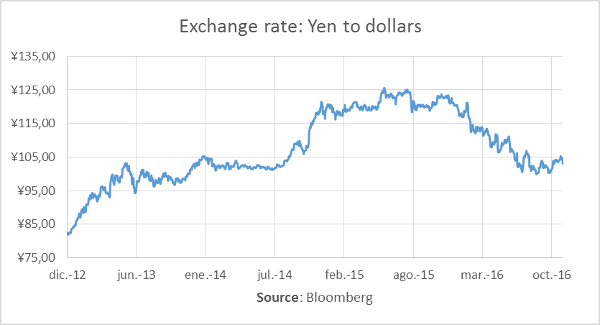

Some blamed an expensive yen for the fall of Japanese exports. If this were true, Abenomics would be a blessing: the accelerated growth of the yen would cause the currency to depreciate against the dollar. And certainly, the effect on the change rate was almost immediate, as the following graph shows.

When Abenomics was announced in December 2012, the yen was trading at an average of ¥82 a dollar. By May 2013, the yen had jumped to ¥100 a dollar—a 22% depreciation in only six months.

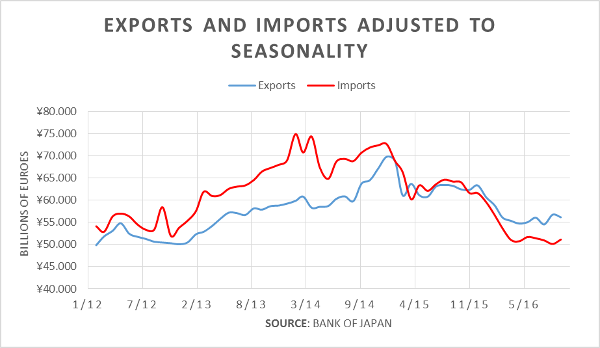

Did it work? The following graph helps respond the question: exports improved at first, but have fallen for 12 consecutive months since September 2015.

Last July, Market Trends published an article criticizing the idea that competitiveness could be gained by depreciating the yen. We concluded that the stimulus package and the consequent depreciation of the yen failed to boost the country’s export sector—a thought contrary to the mainstream.

One’s Gain is Another’s Loss

Why didn’t the depreciation of the yen help exporters? Primarily, because large exporters are also large importers. As a study by the American Economic Association shows, when the economy becomes more complex and productive, the fragmentation of production increases. In other words, the chain of production is spread out among different suppliers in other countries.

For example, to produce a Japanese vehicle it is necessary to import a series of parts that are vital to produce a car in order to sell it abroad. If Japanese companies buy imported supplies, the depreciation of the yen pushes up the marginal costs of producers. This increase of costs does not allow Japanese exporters to gain competitiveness. Even if the yen depreciates, Japanese goods are not produced cheaply because the increase of costs due to the depreciation kills the alleged competitiveness.

Furthermore, the study reminds us that even the most productive companies are increasingly being exposed to fragmentation and are importing supplies in greater numbers than the less productive ones. The Japanese automobile industry probably imports more intermediate supplies than rice-producing companies.

In simpler words, depreciation makes the yen cheaper for foreigners but it does not make goods cheaper for foreigners. This is due to one of the following: either the depreciation raises the costs for exporters or exporters adjust their prices upwards with depreciation.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Edgar Ortiz

Edgar Ortiz has a degree in Law from the Francisco Marroquín University. He holds a master in Austrian Economics at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid. He is the executive director of the Center of Economic and Social Studies (CEES). He is a professor of economics at the Francisco Marroquín University, and he is also an analyst on issues related to the situation at Canal Antigua. He works as an associate lawyer at Estudio Jurídico Rivera.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions