The Battle for the Streaming Market: Netflix, Amazon, HBO and Disney

In the past, Netflix dedicated itself to DVD rentals and competed directly with Blockbuster. Netflix’s differentiating factor was that it sent DVDs by mail, whereas Blockbuster had a network of physical stores.

When Netflix transitioned to streaming, gradually leaving the DVD business behind, it became one of the greatest revenue-growth success stories in history. Netflix completely dominated the streaming market until its current rivals entered the market.

The Number of Netflix Subscribers

Netflix’s recent growth in subscribers is truly astounding. One would expect the growth rate to decline as the company grows. However, Netflix continues increasing its number of subscribers at an accelerated rate to this day.

In 2017 I estimated that in five years—by 2022—Netflix would reach a little over 172.5 million subscribers. My miscalculation was huge (short by approximately 28 percent); nonetheless, my big-picture prediction for 2022 was far more accurate.

Growth costs money. Netflix’s marketing efforts aimed at acquiring new subscribers have multiplied. A few years ago, it offered free subscriptions or ads on social media to attract new clients. Now, Netflix has expanded into traditional marketing channels.

Image: An example of traditional marketing that Netflix began to engage in (2018)

Unit Economics: How Much Does It Cost Netflix to Acquire a New Subscriber?

Netflix’s efforts can be quantified by calculating the advertising cost of acquiring a customer. This estimate assumes that Netflix loses 9 percent of its customers on average per year (called the churn rate) and, more importantly, that this rate is stable over time.

This is an example of the law of diminishing returns (or its equivalent, the law of increasing costs). Each additional dollar invested in advertising will have a worse marginal return than the previous dollar because it is probably directed at a subscriber who is more difficult to persuade.

According to Motley Fool, Netflix’s customer acquisition cost in the US market is already greater than $100 per customer.

Unit Economics: How Much Is a Netflix Subscriber Worth?

To Netflix, the value of a subscriber depends on three factors:

- How much does the subscriber spend per year on the service?

- What is the operating margin?

- How many years does a customer remain a subscriber, on average?

For Netflix, answering these questions is relatively easy. In the case of the US market, we have the following data:

- $14.56 per month x 12 months = $174.72

- 15 percent

- 10 years

Thus, the value of a US subscriber is $175*15%*10 = $250. Increased competition from HBO, Amazon, and others may decrease the expected life of a customer.

The ratio of a customer’s lifetime value to its cost of acquisition is relatively healthy in the US (2.5 times in a saturated market). The question is whether the numbers make sense in the places Netflix is currently growing. Let’s take the example of a Latin American subscriber:

- $7.73 per month x 12 months = $92.76

- 15 percent

- 10 years

This implies a lifetime value of $139.50 per Latin American customer.

Up to here, everything is fine for Netflix. However, as competitors HBO (with HBO Max), Amazon Prime (with Prime Video), Disney (with Disney+), and others enter the market, demand elasticity increases. With more substitutes, customers become more sensitive to changes in prices or content offered.

Moreover, as switching increases, the lifetime value of a customer is reduced since their expected lifespan decreases. Additionally, switching makes any attempt to increase prices more complicated.

Profitability over Subscribers: Netflix’s Bet

My prediction in 2017 was that Netflix was not going to be as profitable as the market believed as its number of subscribers grew.

One of the problems for Netflix was that it was at the mercy of the large content distributors like HBO. It seemed that all the surplus was going to go to the owners of series and movies and that Netflix was going to take a loss.

At that point, Netflix decided to change its business from brokering content to creating content (or at least getting exclusive rights to new content). However, it is not at all easy to create winning content for an audience that is terribly critical, temperamental, and susceptible to short-term fads.

The arrival of HBO with HBO Max and Disney with Disney+ induced a radical change in Netflix’s content library. In just two years, Netflix’s original content has gone from 25 percent of its total content to more than 40 percent (and it is probably close to 50 percent now).

How Much Is Netflix’s Original Content Worth?

We know how much Netflix spends on producing a series. For example, the series Marco Polo cost $10 million per episode, so, before it discontinued the series, Netflix spent a total of $200 million on it. How much was this $200 million investment really worth? And what is the lifespan of a series?

A series is only worth something if it is capable of generating revenue. Does a series that practically nobody watches have economic value? The answer is a resounding no.

However, because of the way that Netflix amortizes (writes off) its content, Marco Polo is now assumed to be worth $50 million four years later (or $20 million, depending on the particular model of amortization Netflix has chosen).

However, if nobody is actually watching Marco Polo, 100 percent of its value should be amortized in the accounting books. The effect of doing so would be that Netflix’s amortization expense would increase and its profit would decrease since the costs would be higher and the revenue lower.

This fits with the idea of economic calculation, in which accounting serves as a tool. This spontaneous order always evolves, and the way we treat investment in series and movies for accounting purposes is a good example of that.

How Does This Compare with Disney?

It appears that much of the content created by Disney has greater staying power. In other words, it has a longer lifespan or a lower amortization rate compared with Netflix.

For example, Disney’s movies The Lion King and Toy Story surely keep a loyal audience every year. In clear contrast, the audience for the first season of The Get Down on Netflix (with an investment of $11 million per episode) is probably nonexistent.

However, seeing Netflix’s enormous investment in creating new content, other studios, like Disney, Amazon Prime, and HBO, are also dramatically increasing their budgets for new content creation.

Paradoxically, this is causing serious problems in the streaming industry.

The Inelastic Supply of Film Production

The current reality of the film industry is that the number of workers—the human capital—is limited. Furthermore, the number of film studios is limited (they are typically subcontracted by Netflix, Amazon, and the like), as is the availability of equipment and cameramen. All of this leads us to conclude that the supply of films and series is inelastic, at least in the short term.

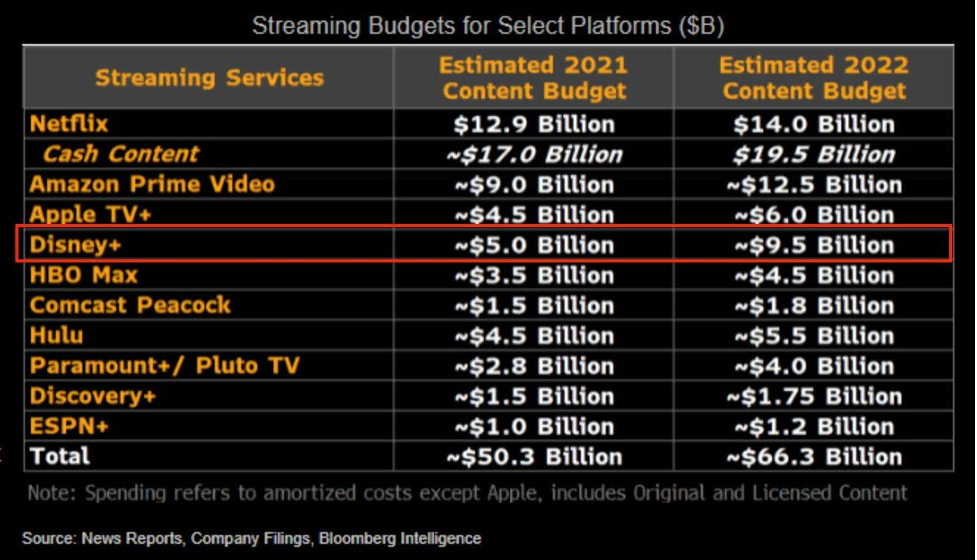

The following are the projected budgets for 2022. According to the Financial Times, more than $115 billion will be invested in content production in 2022.

Source: Bloomberg

The problem is that there is no capacity for increasing production. The streaming platforms with the most purchasing power, including Netflix, Amazon, Disney, and HBO, will demand greater film capacity. This does not include small producers of films and series, as these compete for the same resources with less purchasing power.

More money does not mean more content; more money, in the short term, means higher prices for the same film capacity.

The result has been a significant increase in production prices and a noticeable shortage of the production factors necessary for film production.

Production studios are delighted with the boom in film investments (I imagine UFM Film School is too), but the question is how sustainable this race to create more and more film content will be in a context of unprecedented rivalry.

How Is This Race to the Bottom Financed?

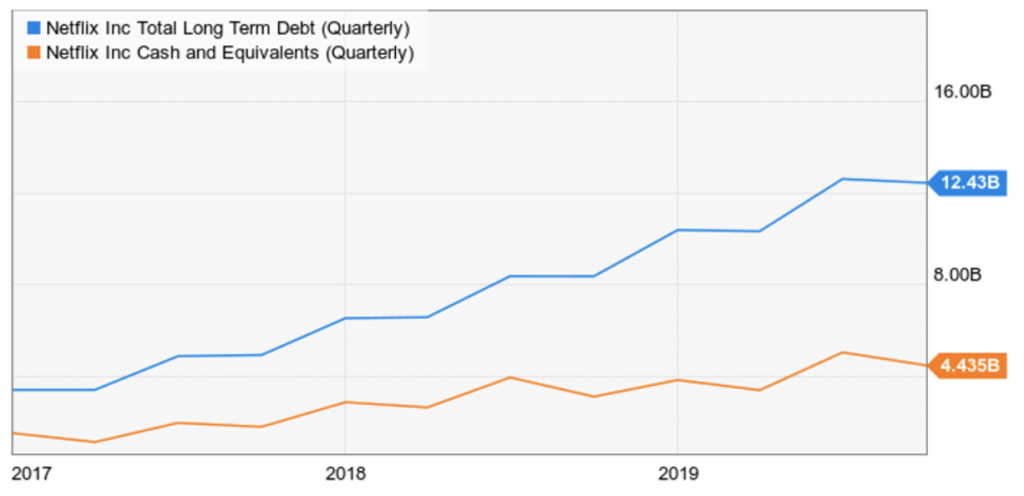

The answer is: with debt. Companies like Netflix, which even now appears to be overindebted, continue to borrow at lower and lower interest rates.

This is exactly what Austrian business cycle theory predicts: an unsustainable, credit-financed boom that ends in a bidding for resources among producers.

And this indebtedness has gone hand in hand, curiously, with a decrease in the interest rate Netflix pays.

At the end of 2021, the interest rate Netflix was paying was the lowest in the last five years. The drop in interest paid by Netflix came even though its debt increased from $5.5 billion to more than $13 billion in that same period. The really uncomfortable thing for the streaming giant is that if it were incredibly profitable, this debt would not have been necessary.

Is the Investment Boom in Movies and Series Sustainable?

It is very likely that these big investments in film content will not translate to greater revenue for the companies making the investments. The only thing that is happening, for the time being, is that production costs are increasing as companies seek to attract customers in an increasingly competitive market. It is very possible that the greater investments in content will not translate to more and better series and movies.

Legal notice: the analysis contained in this article is the exclusive work of its author, the assertions made are not necessarily shared nor are they the official position of the Francisco Marroquín University.

-

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Olav Dirkmaat

Olav Dirkmaat is professor in economics at the Business School of Universidad Francisco Marroquín. Before, he was VP at Nxchange and precious metals analyst at GoldRepublic. He has a PhD in Economics from the King Juan Carlos University in Madrid. He has a master in Austrian Economics from the same university, as well as a master in Marketing Strategy from the VU University in Amsterdam. He is also the translator of Human Action of Ludwig von Mises into Dutch. He has a passion for investing, and manages funds for relatives, looking for investment opportunities in markets that are extremely over- or undervalued.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions