What Is the Future of the Guatemalan Banking System?

By Clynton R. López F. August 05, 2015

Translated from Spanish by Daniel Contreras

The Guatemalan banking system, much like the country’s macroeconomic indicators, has been very stable the last few years. The bankruptcies that affected banks and financial intermediaries seem to have been forgotten. In recent history, bankruptcies by financial intermediaries are due to technical mismanagement, scams, or government corruption.

The bankruptcies of the so-called twin banks, in the 1990s, and Banco de Comercio and Banco del Café, at the beginning of this century, were widely perceived by the public to involve fraud and government corruption. The bankruptcies that financial intermediaries went through in the 1990s were mostly due to technical mismanagement.

This article focuses on the bankruptcies of the 1990s that were brought about by technical mismanagement; although it’s important to take a brief look at how other bankruptcies affected how banks are managed today. The failures of the twin banks, Banco del Café, and Banco de Comercio generated a loss of confidence in regulators. Most likely, the laws needed to handle bank interventions and liquidations were not in place, but the perception was that rules were broken. One example is the Guatemalan Depositors Insurance Fund. When these banks failed, it was unclear who was on tap for the losses. In the process, depositors were left to pay part of the bill, creating a loss of confidence in the system and regulators.

The bankruptcies that financial intermediaries went through in the 1990s were due to maturity mismatches. These nonbanking institutions placed long-term assets (like automobile financing) with short-term deposits.

What triggered these bankruptcies was a liquidity shortfall—according to those involved at the time—derived from an attempt to defend the exchange rate. The Bank of Guatemala adopted this measure by acquiring and holding currency reserves.

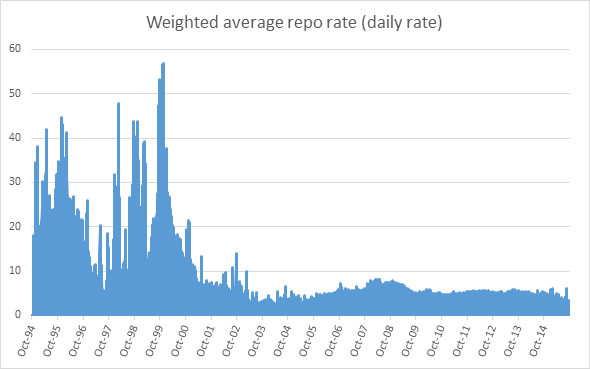

This liquidity shortfall put pressure on all financial intermediaries with maturity mismatches causing their downfall. As we see in graph 1, the 1990’s repo rate, especially after 1996, almost reached 60% in the overnight market.

Graph 1

Source: Bank of Guatemala

Financial intermediaries that were short-term financed but had long-term loans could not support the short-term interest rate rise.

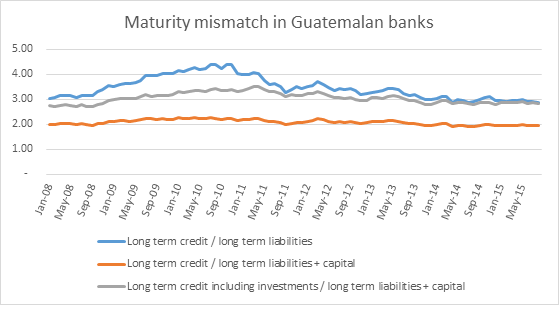

Did the banking sector learn from this experience? Probably. If the central bank maintains liquidity at current levels, the maturity mismatch is manageable and does not pose a risk. As it stands, the monetary base in Guatemala has grown in the last twenty years and the compound annual growth rate is 9.73%, with M1 of 9.8% during the same period. In other words, the Guatemalan financial market is highly liquid.

Graph 2 shows the maturity mismatch of the national bank in terms of long-term financing granted, with raised short-term funds. These numbers are estimates for the last seven years, calculated using data published by the Superintendency of Banks in Guatemala (SIB). The banking system and macroeconomic indicators are stable, but what is the price of this stability? Probably inflation, and if inflation is low, pressure on the national bank through open market operations. We cover this and other topics about the Guatemalan economy in our second quarter UFM Market Trends report.

Graph 2

Source: Superintendency of Banks in Guatemala (SIB)

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Clynton López

Clynton López is a professor at the Francisco Marroquín University since 2002 in the areas of economics and philosophy. He has a degree in Economics with a specialization in Finance from the Francisco Marroquín University and a master in Economics from the same university, both Magna Cum Laude. He studied executive programs at Boston University on Managerial Economics & Corporate Finance, the Master of Philosophy at the Rafael Landívar University (specialization in phenomenology), and the Post Graduate Degree in INCAE for Senior Management. In the professional field he has more than 10 years of management experience in banking and financial companies in Guatemala, California and Puerto Rico, and is a member of the Mont Pelerin Society.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions