The Future of Spain’s Real Estate Market

By Daniel Fernández Méndez December, 22 2015

Translated from Spanish by Katarina Hall

The real estate market is generally one of the most pro-cyclical that exists in modern economies. Usually, this market is one of the main objects of over-investment during the upswing phases of the economic cycle. Accordingly, real estate is one of the markets that suffers the most when bubbles burst.

In the beginning, Spain’s bubble seemed to signal that the housing market could have high returns. This is because since the middle of the 1990s Spain displayed an incipient economic development, a complete industrial reconversion, a large supply of human capital at a reasonable cost (a good cost-to-productivity ratio), and at the same time entered the Euro project. Faced with a situation like this, it seemed logical to expect a greater housing demand (whether it was from nationals who tend to become independent sooner, or, above all, by immigrants who were coming to the country because of its economic development).

In every bubble, there is a basis that supports the initial stage of inflation of the bubble itself. However, what causes the price to move away from present value cash flows? In other words, what causes housing prices to grow or decrease at a faster pace than their rent? Logically, one would think that both prices grow and decrease evenly—after all, purchasing a house is the same as prepaying all of the rents it could provide.

There are two ways of answering this question. On the one hand, we have bubbles that feed on the credit market (although as the English author Thomas Tooke pointed out in the 19th century, this price speculation precedes that of the credit market). The central bank and banking legislation usually favor mortgage loans (and state loans) above other credit rates. Furthermore, low interest rates encouraged (although not always maintained) by the central bank increase the present value of all future goods. When it comes to housing, the increase in present value is immense (we have to think about how changes in the rent’s present value in 30 years against changes in interest rates are magnified).

On the other hand, non-banking legislation encourages the bubble to continue for longer than we want it to. In this sense, we have tax incentives for mortgage debts, as well as public administrations that act as contractors and sell at low prices to special interest groups they deem favorable.

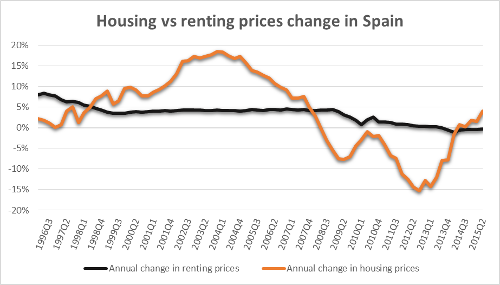

Source: Based on data from the European Central Bank and Eurostat.

This explains how, since 1998, housing prices have grown steadily over rent prices. This marked the beginning of the bubble, as asset prices rose without increasing returns. Since 2008, we have seen the opposite happen: the bubble has burst and past mistakes have been adjusted through a significant correction in housing prices.

We also see how Spain’s housing prices have been more volatile than the Eurozone average. Beginning in 1998, housing prices in Spain steadily rose above those of the rest of the Eurozone. Since 2008, the opposite movement has occurred.

Source: Based on data from the European Central Bank and Eurostat.

Both graphs show that we are re-living a “new 1998,” a bubble period in the market. Housing prices continue to increase more than rent prices and over housing prices in the rest of the Eurozone. Although it is still early to reach a conclusion, the movement could be the result of the market overcorrecting past prices and currently readjusting itself (this time upwards).

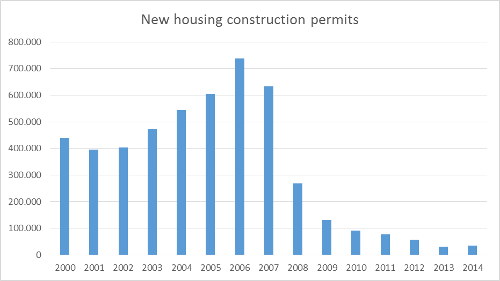

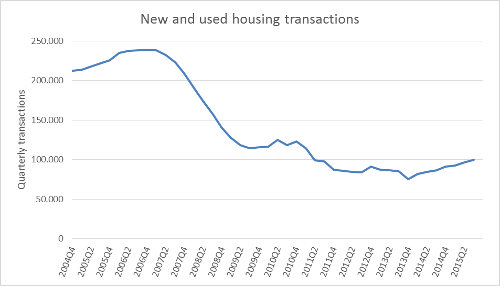

Similarly, we see that 2014 is the first year since 2006 in which construction permits for new houses have increased. However, they are still less than one-tenth of those requested in 2000. Housing transactions also accelerated at the beginning of 2014. The market’s dynamism seems to be starting.

We can also see how the almost complete absence of new construction makes the housing stock accumulated throughout the bubble decline, even if at a slow pace.

Source: Ministry of Development of Spain.

Source: Data from the Ministry of Development of Spain elaboration. The data shown is a moving average of the previous four periods.

We can also see how the almost complete absence of new construction makes the housing stock accumulated throughout the bubble decline, even if at a slow pace.

Source: Ministry of Development of Spain.

Overall, it seems as if Spain’s real estate market is beginning to “wake up.” It is possible that we are facing the beginning of a new bubble. If this is the case, now would be a good time to buy real estate—as long as you are willing to get rid of it once the housing market signals the end of the bubble. If the European Central Bank’s credit policy and the rest of its measures that support such a market do not feed the new bubble, then the construction market ought to gradually increase its activity, even if at a much more modest level than before. Prices ought not to rise quickly due to the still considerable amount of new housing stock that remains unsold.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Daniel Fernández

Daniel Fernández is the founder of UFM Market Trends and professor of economics at the Francisco Marroquín University. He holds a PhD in Applied Economics at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid and was also a fellow at the Mises Institute. He holds a master in Austrian Economics the Rey Juan Carlos University and a master in Applied Economics from the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Great, Good insights on real market and trends, the real estate market is constantly evolving and 2017 is shaping up to be another year of change.