Italian Banks Are The European Economy’s New Sword of Damocles

The Italian banking crisis can be said to start with the stress tests of the summer of 2016 and the episode of the Mode dei Pashi bank, which needed a bailout of 6,600 million euros. At the end of June 2017 the crisis seems far from over, as the Italian government injected 17.2 billion euros into two Venetian banks—5,200 million directly and 12,000 in the form of guarantees. This happened even though the European Commission considered that both Venetian banks did not pose a systematic risk.

How have the European financial systems reacted to the Italian crisis? Has there been a contagion effect?

Ability to finance European banking systems in the market

First, let’s see how the financing of banking systems in the ECB has changed over the course of a year for some Eurozone countries. This indicates the market’s distrust of the banking systems of several countries.

Almost all of the national financial systems have worsened in this section with respect to last year. Most of the countries that supposedly have no banking problems and have less financing from the ECB, have seen a decline. Therefore, there is a clear contagion effect from Italian banks to the rest of the European banks.

|

Liabilities financed by ECB |

May 2016 |

May 2017 |

|

Netherlands |

0.6% |

1.4% |

|

Germany |

0.9% |

1.6% |

|

Ireland |

1.9% |

1.8% |

|

Italy |

4.8% |

8.1% |

|

Spain |

5.9% |

8.0% |

|

Portugal |

7.0% |

7.1% |

|

Greece |

35.0% |

24.2% |

Source: ECB

The case of Ireland, Portugal, and above all Greece are striking. We would expect the contagion effect to focus primarily on what are perceived as weaker links. The lack of contagion effect in these countries could be due to an overcapitalization of the sector due to financial bailouts or a real restructuring of the sector.

Although having been bailed out, Spain has been affected along with the rest of European banks. This could be because the restructuring of the sector has not ended and its is thought to have weaknesses, or that the Spanish banking system has its own internal problems.

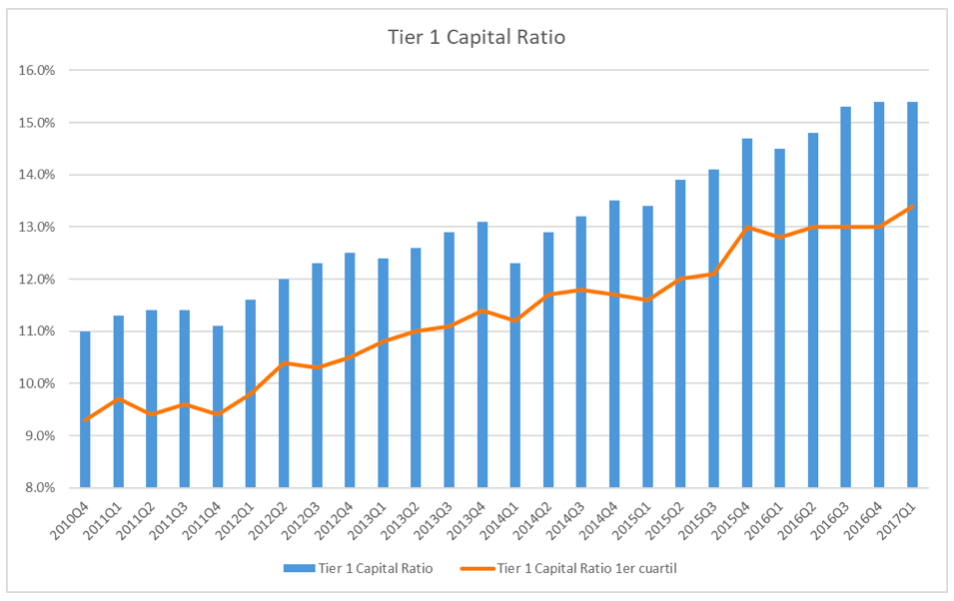

Capitalization Ratio of Eurozone banks

The capitalization of Banks is now far better than in previous banking crises, making the sector stronger in the face of new crises.

Both the average capitalization and in tyhe first quartile capitalization—weaker banks—have seen their capitalization increase.

This means that the banking’s sector’s capacity to withstand shocks has increased. Their ability to resist autonomously—without resorting to bailouts—to a contagion effect is now significantly greater—though obviously not infinite.

Source: EBA.

Debt/equity ratio of Eurozone Banks

If we look at the debt/equity ratio, we can see the same trend: the financial position of banks is stronger today than it was a few years ago.

The percentage of banks with a debt/equity multiple of less than 12—a financially sound position—has significantly increased since the end of 2014, from 10% to 18%

The percentage of banks with a very large debt/equity multiple and in a financially dangerous position—multiple larger than 15—has decreased sharply, from 63% in 2016 to 48% in 2017.

|

Debt/Equity Ratio Banks (% of total banks) |

<12X |

>15X |

|

2014Q4 |

10.5% |

63.1% |

|

2015Q1 |

10.0% |

57.2% |

|

2015Q2 |

7.3% |

51.3% |

|

2015Q3 |

10.5% |

51.7% |

|

2015Q4 |

12.5% |

50.8% |

|

2016Q1 |

9.5% |

54.7% |

|

2016Q2 |

11.0% |

56.0% |

|

2016Q3 |

16.3% |

51.2% |

|

2016Q4 |

16.3% |

54.7% |

|

2017Q1 |

17.9% |

47.9% |

Source: EBA. Percentage of banks with a debt/equity ratio lower than 12X and higher than 15X

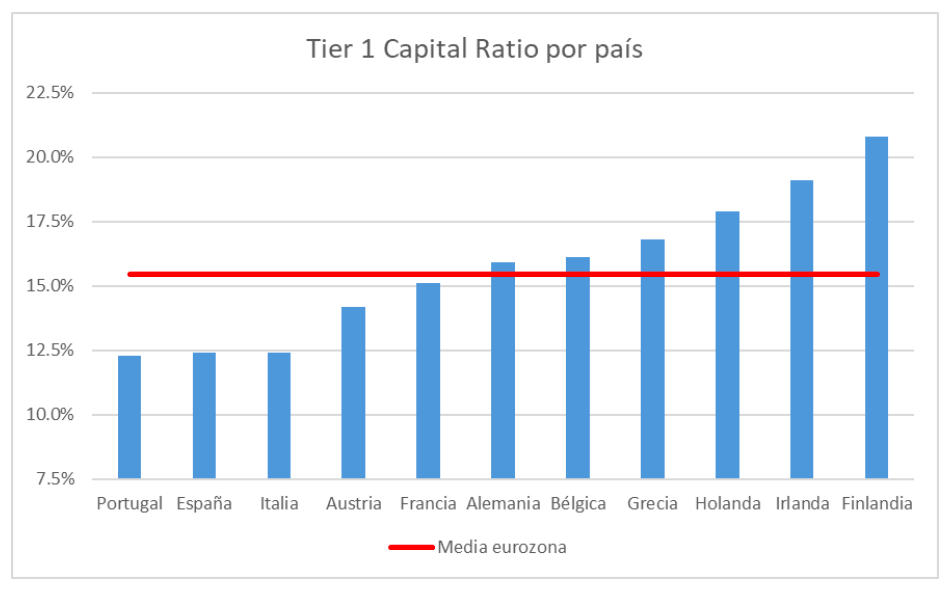

Bank Capitalization by Country

If we break down capitalization by country, we can see that the countries in most need of financing from the ECB are the ones that also have a less capitalized banking sector; i.e., the market does not “punish” without a reason. The most reckless and less capitalized banking sectors are the ones receiving less financing.

Source: BEA.

Graph: Tier 1 Capital Ratio by country. Red: Eurozone average

Seeing that Ireland is the second country among the Eurozone’s greater countries with the highest capitalized banks, we can understand how there has not been a contagion effect. In the end, economic theory is never wrong: markets do not attack, they only defend.

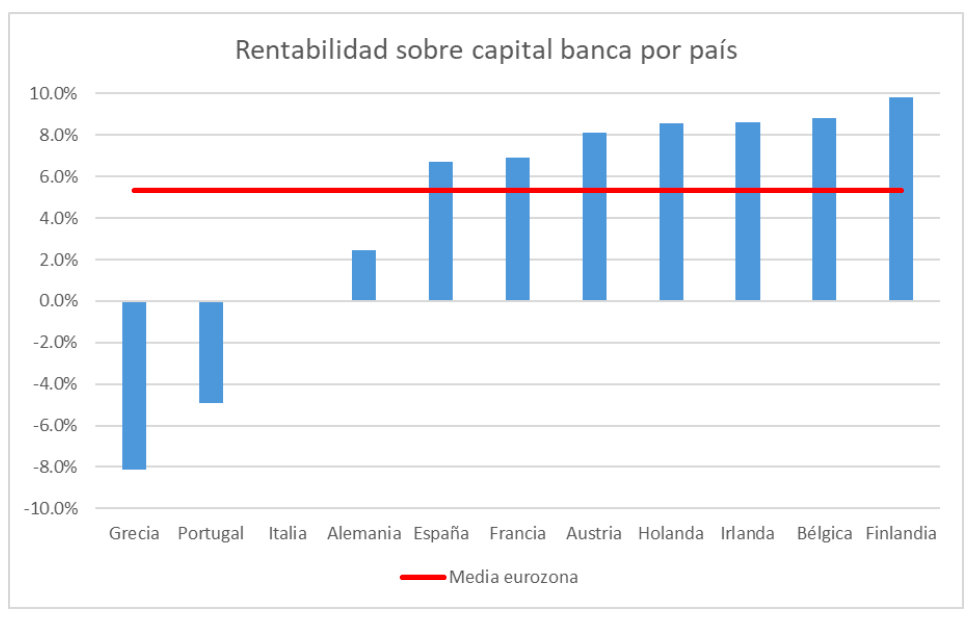

Bank Profitability By Country.

The future capitalization of countries with the most problems—Spain, Portugal, and Italy—depend of their capacity to generate benefits—and not to distribute them.

Source: BEA. The data is the average of profitability of the last 4 quarters.

Graph: Bank profitability by country. Red: Eurozone average.

Portugal and Italy are going to have problems recapitalizing without new public aid, while Spain’s banking sector can accumulate undivided benefits to increase its capital ratio.

If the Portuguese economic growth lasts, it can boost the profitability of its banking sector and avoid new capitalizations with public aid. Italy’s case seems more complicated, since its economic growth is still weak.

The Greek financial sector has received millions from different bailouts, therefore, Greek banks still have a good capital ratio despite of the huge losses they accumulated. However, if Greek banks fail to restructure and the economy does not start growing strongly, Greece will need another bail out.

We should highlight German banks, which although have a good capital ratio have serious problems generating profits. This could be a problem in the future. In fact, we can say that the Netherlands has become the new benchmark in banking risk, leaving Germany in the background.

Conclusion

To sum up, the Eurozone’s banking sector shows a strength that will allow it to face any kind of shock with more certainty.

There are still weak links , particularly Spain, Italy, and Portugal. Spain could recapitalize privately from banking profits. Italy has almost no profitability and Portugal is in the negative territory, therefore their possibility to increase capital privately is limited.

Fortunately, Portugal has started to grow strongly. If it were to continue growing, it is possible that its banking sector could turn losses into profits, and could increase its capital privately.

Italy faces a more serious problem: it’s economy is among those growing the least and it does not seem that the country’s situation will change in the near future. This means that the bank’s profitability ratios may not rebound and the possibility to increase capital privately becomes complicated.

You can see the full report on the Eurozone economy and its banking situation by clicking here.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Daniel Fernández

Daniel Fernández is the founder of UFM Market Trends and professor of economics at the Francisco Marroquín University. He holds a PhD in Applied Economics at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid and was also a fellow at the Mises Institute. He holds a master in Austrian Economics the Rey Juan Carlos University and a master in Applied Economics from the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions