Inflation Target or GDP Target: More Ideology?

The disappointing results of the United States’ economic growth for the second quarter—1.1%—and of other developed economies like Japan and the Eurozone, reopened a debate: are the central banks of these countries doing their job properly?

Since the early 80s, the Federal Reserve left the classical monetarist approach to controlling inflation because the velocity of money—which was assumed to be fixed and exogenous—ceased to be predictable. For around 30 years since then, central banks have been operating under two main objectives: inflation and employment levels.

In recent years, specially after 2008, the inflation target has not yielded the expected economic growth results. The main reason seems to be that traders did not respond as monetary authorities expected. Furthermore, massive bond purchases by monetary authorities are not reflected in the credit granted by financial institutions. Inflation levels are still below target.

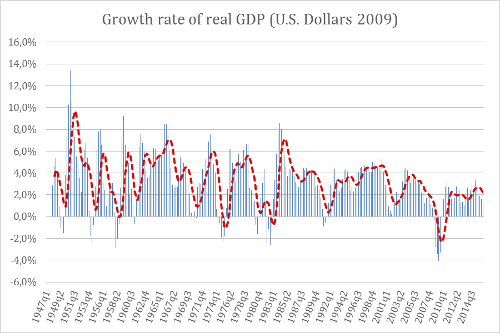

Graph 1

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Graph 1 shows a time series of the real quarterly annual growth rate of the United States since 1947. Since the inflation targets became the modus operandi of the Federal Reserve in the 80s, the volatility of growth appeared to be reduced. Today, the central bank debate focuses on whether they should continue to use the inflation target as the main objective for monetary policies or if it should change to a nominal GDP target.

What would a change from an inflation target to a nominal GDP growth target imply?

The change would be more radical than it seems. When an inflation target is set—usually 2% for a developed country and 4% for a poorer, emerging economy—inflation is constantly being monitored against the real growth of the economy. The real growth sets the limits for the growth of monetary aggregates driven by central banks. If the objective changes, the nominal GDP target would become the new objective for monetary policy. Unfortunately, central banks are never one hundred percent independent of political power—although some are more than others. Monetary policy would then take form based on this objective. This monetary policy would have no limit other than the objective taken by central banks. In other words, this means that when ideology does not work it isn’t because it is not pure enough and needs more ideology; according to the assumptions behind this theory, central banks should not have established limits to fulfill their monetary policies.

If this debate is successful in politics, central banks will eventually return to what they once were. Without limits for central banks, regardless of a gold standard or inflation target, the world would surely face problems of excess money. These problems do not only include high prices, as is usually understood. Excess money problems are current and intertemporal economic coordination problems. If the inflation target is changed to a nominal GDP target, in the long term we could expect coordination problems, including bad investments, excess consumption, and excess investments in targeted sectors.

Taking into account that the monetary policy of a central bank can impoverish millions of people if done irresponsibly, a more prudent route would be to re-evaluate whether the response of the economic agents to the monetary policy is the correct one after the 2008 crisis. By not responding to the changes in economic policy that resulted from 2008, money would become neutral. This would imply something very simple: traders may want to return to a more orthodox economics where growth is generated by savings, where the leverage level is reduced, and where we might return to a new old economy. The popular and respected magazine The Economist brings up this debate, something we hope will be lost by those who promote a new era. Although in reality it might seem as if we were returning to an old ideology of giving powers to politics through the central bank.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Clynton López

Clynton López is a professor at the Francisco Marroquín University since 2002 in the areas of economics and philosophy. He has a degree in Economics with a specialization in Finance from the Francisco Marroquín University and a master in Economics from the same university, both Magna Cum Laude. He studied executive programs at Boston University on Managerial Economics & Corporate Finance, the Master of Philosophy at the Rafael Landívar University (specialization in phenomenology), and the Post Graduate Degree in INCAE for Senior Management. In the professional field he has more than 10 years of management experience in banking and financial companies in Guatemala, California and Puerto Rico, and is a member of the Mont Pelerin Society.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions