A Guide to the UK Financial Panic

We have known for some time that the sharp rise in interest rates being implemented by central banks is going to hurt the economy and the financial sector in particular. We did not know where the financial sector would start breaking down. The first financial panic of 2022 has already taken hold in the United Kingdom. It has forced a reversal of the contractionary monetary policy of the—once all-powerful—Bank of England.

This article will analyze both the roots and the consequences of the British financial panic.

Turbulent Times in the UK: Why Is the Pound Plummeting?

Recent times have been very turbulent for the world economy, and especially the already-battered British economy. In the span of a week, the following has happened:

- A tax-cut announcement of some 45 billion pounds sterling, a cut probably unparalleled since the 1980s

- A fall in the pound sterling on the foreign exchange market to a degree not seen since the 1970s

- Financial panic

If you think you’ve had a bad week at work, console yourself by remembering the week the UK economy had.

Let’s try, therefore, to shed some light on the week of economic events in the UK, with emphasis on the financial panic.

- Tax Cuts

First, let’s briefly consider the tax cut. Aggressive tax cuts have the huge economic benefit of incentivizing long-term economic growth. However, they also have the cost of leaving a fiscal hole by causing tax revenues to tank. Proponents of the Laffer curve argue that economic growth generates new tax revenues that could offset the drop in revenue from lower tax rates. Although the theory behind the Laffer curve is sound, and of course there is always some offsetting effect, the UK economy is certainly on the left side of the Laffer curve: the extra income from higher economic growth will not fully compensate for the initial fall in tax revenue.

Therefore, the fiscal hole must be filled in some way. One option is to lower public spending. However, Liz Truss’s new government announced it would increase public spending to subsidize energy consumption, thus digging a second fiscal hole.

- The Pound Sterling Plummets

If the UK government had little debt, the pound’s problems might not have appeared. The trouble is that the government is hyperindebted and has little extra borrowing capacity. Therefore, the market understood, correctly, that the huge expansion of government debt was going to end up fattening the Bank of England’s balance sheet.

The inflation that half of the world suffers today is mainly due to the abuse of monetary policy to finance gigantic, and outrageously irresponsible, public deficit spending. As the inflationary fire scorches the world economy, the British government thought it was a good idea to add to the fire the same fuel that started it. This does not seem to be the best idea.

Panic in the City of London: The Bond-Market Crash

Any system under stress begins to break down at its weakest links. It is therefore not surprising that the international financial system is beginning its breakdown in the UK (with the consent of the investment bank Credit Suisse and Chinese banks).

Britain’s problems began with the rate hikes that occurred in almost the entire world this year. However, to focus on the current panic, let us look at what has happened to the price of UK bonds in the last few days.

Since the price of bonds follows an inverse path to that of the interest rate, a rising interest rate is equivalent to a falling bond price.

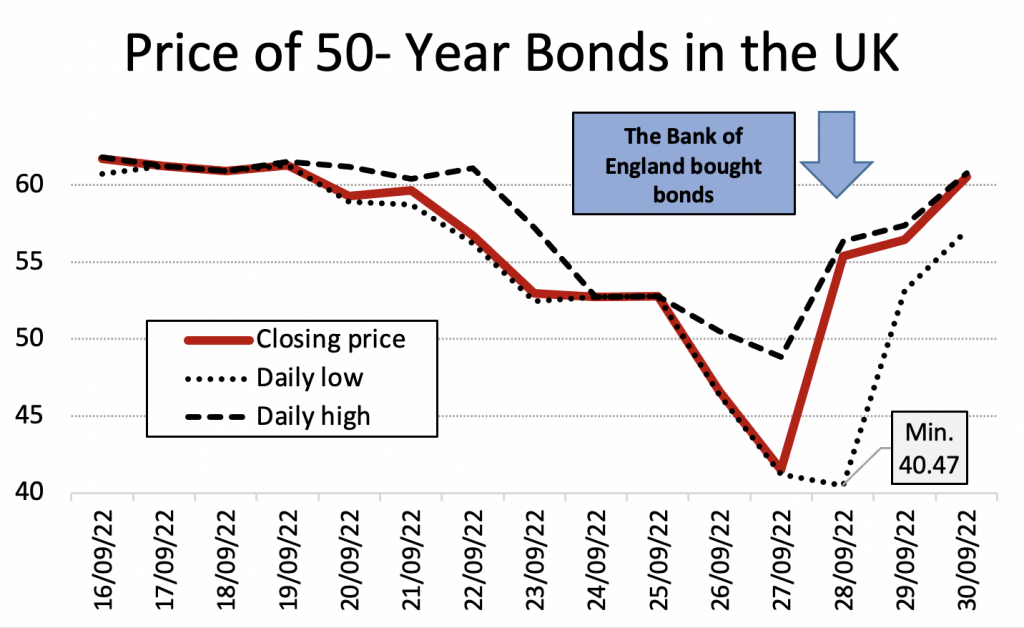

Figure 1

Source: Prepared by the author with data from Investing.com

Figure 1 shows that UK bonds issued at long maturities, specifically fifty-year bonds, lost a third of their value in just one week. The loss in value came after Liz Truss’s government announced the policies behind the two fiscal gaps. After several days of market carnage, the Bank of England decided on September 28 to intervene by making massive bond purchases and at least temporarily preventing bonds from plummeting further.

Figure 1, and virtually all of the following analysis, considers the price of bonds rather than the interest rate or bond yield because it is makes it much easier to see that a fall in the price of bonds generates huge holes in the balance sheets of the financial intermediaries that hold those bonds.

Who Has Suffered from the British Financial Panic?

Pension funds face certain financial regulations that purport to provide extra security in a market that is especially sensitive to swings in financial markets. The authorities are supposedly concerned with providing rules to ensure that retirees can enjoy their pensions and avoid poverty in old age.

For this reason, one of the main types of financial intermediary holding government bonds and fixed-income assets in general is the pension fund. We could ask Greek pension funds, or better yet, Greek pensioners, whether the regulation-induced premium on investing in government bonds is a good idea (when Greece defaulted, investors lost everything). In any case, regulation is supposed to protect us, and public debt is also supposed to protect against financial problems arising from private investments. Therefore, pension funds are pushed, but not necessarily forced, to invest substantially in government bonds. For example, required financial ratios and coverage for government bonds are less demanding than for other assets (and some legislation outright requires pension funds to invest in government bonds). This is the reason why pension funds are currently suffering greatly.

As if this were not enough, pension funds are usually pushed, if not forced, to pursue political agendas that have nothing to do with their fundamental objective. This is the case, for example, with the European Union’s directives for supervision of institutions for occupational retirement provisions, which push pension funds to invest in green bonds, thus getting pensioners to finance projects with environmental objectives even if the projects yield relatively low returns. In other words, regulations that purport to protect savers and future pensioners are actually harming them. Of course, no one has the time or inclination to read European regulations, so the pension fund disaster looks like a failure of the free market.

Returning to the UK financial panic, we have already seen that UK government bonds fell 33 percent in just one week, so we can imagine that the hit to the balance sheets of UK pension funds has been very hard.

But the problems of the pension funds go far beyond what we are beginning to see, and the British pension funds themselves have helped cause the collapse in the price of British bonds.

Financial Repression and Pension Funds

The pension fund problem has been present for years and stems from the financial repression the developed world has been experiencing since roughly 2010.

By financial repression, we mean the implementation of negative real interest rates, also known as the euthanasia of the saver. Negative rates imply that the yields on financial assets considered safe, typically government bonds, are lower than the rate of inflation. The financial repression has been so severe that in recent years it has even often been considered normal for billions of euros and yen of debt to yield negative nominal interest rates. A negative nominal rate means that those who have bought public debt end up paying money to the debtor instead of receiving interest in compensation for financing them. This is clearly just short of financial insanity and is only possible in a world of financial repression. It also points to an unparalleled bubble in the bond market, a bubble that is currently bursting.

Financial repression was instituted to prevent irresponsible politicians from putting public accounts in order. If readers want to find a culprit for the world’s economic problems, they must look at the twenty-first-century politicians responsible for crafting public budgets.

If we combine negative nominal interest rates with the legal nudges pushing pension funds to buy public debt, we get the full picture of financial repression. Something similar happens with commercial banks, which are also incentivized, if not forced, to buy certain types of assets, especially government bonds. Therefore, savers never willingly directed their savings to public debt but did so because there was no other option. That private savings continued to be directed for years to finance profligate states and that, furthermore, they were paid to finance those states does not make any economic sense. It only makes sense under financial repression.

The financial repression has led pension funds to get very imaginative—so much so that they have taken far more risk than they should have in a desperate attempt to maintain positive returns. However, there is more to understand about the UK’s financial panic.

The Controversial Investment Strategy of British Pension Funds

Before talking about British pension funds’ investment strategies, we must explain a few things about pension funds.

First, a defined-benefit pension is usually contracted by private companies or public entities for their employees. They are called defined benefit because they promise to pay a specific amount that is usually revaluated with inflation.

There are also defined-contribution pension funds, which work in exactly the same way as traditional mutual funds. The employer (or the employee) pays a specific amount but does not know what the pension will be when the employee retires. The employee’s pension will depend on how well the fund (which is financially no different from an investment fund) is managed.

Pension funds linked to defined-benefit pensions have set off alarm bells in the UK.[1]

In both types of pension funds, future retirees share exactly the same goal: to earn income in their old age. However, two types of pension funds’ participants are treated very differently:

- In defined-contribution pension funds, similarly to traditional mutual funds, when participants retire, the net asset value of the fund is calculated and the corresponding amount is paid to the retiree.

- In defined-benefit pension funds, participants are treated as if they were creditors. The pension fund can treat the payment obligation just like a debt and can quite accurately calculate how much to pay, when, and to whom.

This has led to an investment strategy known as liability-driven investment, or LDI, in which the pension fund seeks to obtain assets capable of meeting its defined payments when needed. It also seeks to acquire assets that will provide a sufficient return to compensate for the possible (inflation-driven) revaluation of its liabilities. Therefore, LDI seeks to balance a pension fund’s assets with its liabilities.

This is an imperfect application of the principle of matching maturities and risks. In other words, LDI is financially sound. But the devil is in the details, and it will soon be clear that the devil will come in through the back door.

Leveraged LDI: The Big Bet for UK Pension Funds

Both the UK pension funds and the regulator itself thought it was a good idea for defined-benefit pension funds to pursue LDI.

If it was such a good idea, why and how did the UK financial panic occur and how did the pension funds become involved?

Let’s return to the concept of financial repression. Imagine a financially healthy world where real interest rates on debt are positive. In this world, LDI pension fund managers have the easiest job in the world, even if they are legally pushed to buy government debt. They only have to buy debt with a term equal to or shorter than the term to which pension payments are committed. In other words, they only have to match cash inflows with cash outflows, and they can do so through foreign direct investment: buying assets with a final payment that matches the final payment needed for each future pensioner. Their fund has no interest rate risk and, by investing in supposedly solid assets, minimizes the risk of default.

Unfortunately, such a world has been unknown almost anywhere since 2010, the year that ushered in a world of financial repression. How does this dystopian world affect UK pension funds? It forces them to take more risks; specifically, they are pushed to take positions in assets that have higher returns but also higher risks, which they accept to compensate for the increase in liabilities due to inflation.

One risk-taking strategy is to lever up. Leveraging is a financial strategy that uses debt to increase the return of an asset. If I put 100 percent of my own capital in debt that pays 5 percent interest and matures in one year, at the end of the year I will have a return of 5 percent. However, I could borrow and take a long position in the same asset. If I can borrow a dollar for every dollar of my equity, I can double my original position. Therefore, on the asset side, with exactly the same capital, I can increase the return from 5 percent to 10 percent. Of course, I would have to pay interest on the borrowed money, which we can suppose is 2 percent per year. Thus, I can use leverage to increase the return on investment from 5 percent to 8 percent. Suppose that, instead of borrowing a dollar for every dollar of equity, I could borrow ten or twenty dollars. Many people in capital markets are highly levered in this way.

While leveraging offers increased returns, it also has a drawback. If the price of the asset an investor purchased were to fall, they could lose all of their capital quickly. When an investor has a dollar of debt for every dollar of equity, their leverage is two to one because there are two units of assets for every unit of their equity. In this scenario, a 50 percent drop in the price of the asset would cause a 100 percent drop in the investor’s capital (if they buy an asset and finance half of it with debt, a 50 percent drop in the price of the asset means that its sale could only cover the debt payment, so they would be left with nothing). The higher the leverage is, the easier it is for the price drop to cause the capital to vanish entirely.

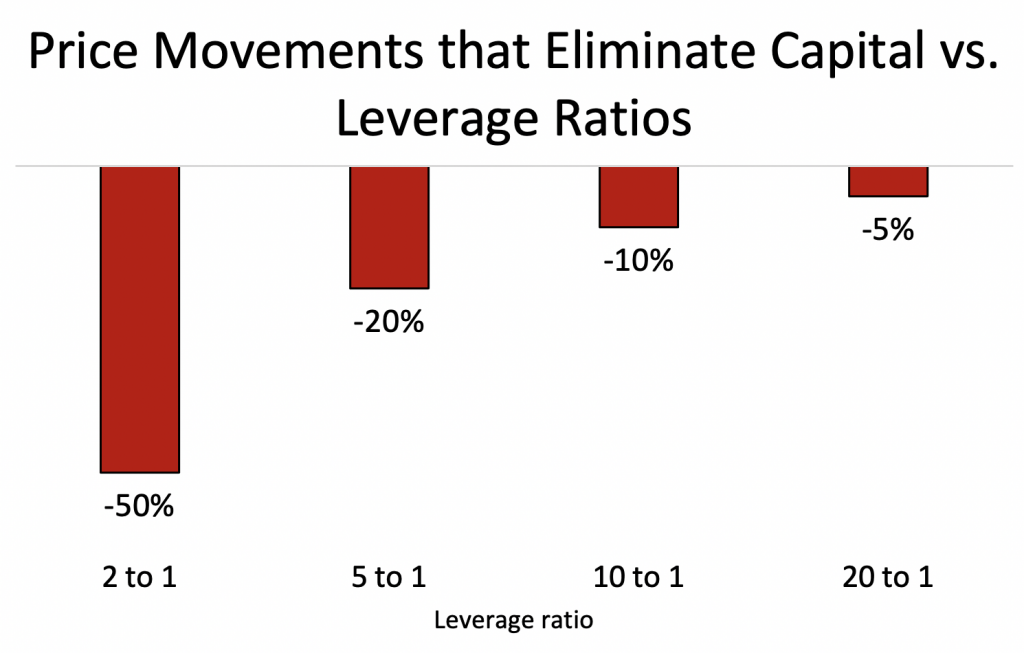

Figure 2

Note: The leverage ratio used is the equity multiplier.

Figure 2 provides examples of price drops that cause equity to vanish under different leverage ratios. When the leverage ratio is ten to one, a drop of 10 percent in the value of the asset would cause a total loss of equity. If the leverage ratio is twenty to one, a drop of 5 percent would be enough to cause the equity to vanish.

When leveraged positions are taken in assets and all of the equity is wiped out, a margin call results. A margin call is a call by the creditor for the investor to make purchases in the capital market. Of course, the call can be carried out, for example, through an alert on an online brokerage account. The call is, in reality, a demand. The creditor does not wish to take risks and knows that the investor’s equity has vanished. Thus, the creditor says to the investor, “If you want to keep your position open, you will have to provide more collateral. Otherwise, I will sell your assets and cancel the debt you owe me; you will be left with no capital.” Providing more collateral means that providing more assurance to the creditor that the debtor will pay. In other words, the creditor demands that the debtor deposit more money or other assets that can be sold if the prices of the investor’s assets continue to drop.

There are many ways to increase leverage, many of which involve taking positions in financial derivatives. If the derivative position falls sharply in price, the investor’s capital can be completely wiped out and they will face a margin call.

The UK pension funds have, in attempting to escape the financial repression, taken leveraged positions. For a long time, this strategy worked very well and the pension funds achieved returns on their assets that were high enough to match their liabilities. Leverage helped to increase the return on assets and at least temporarily to circumvent financial repression. But the higher returns in good economic times turned into skyrocketing losses in the time of financial trouble that came with the recent large interest rate hikes we discussed earlier.

Margin Calls on Pension Funds

The many UK pension funds that had leveraged positions usually had them in financial derivatives of government bonds. When the government announced that it would increase the fiscal deficit to an unprecedented level, its bonds were oversold. The resulting fall in price—as high as 33 percent—is causing UK pension funds with leveraged exposure to this asset to begin to see the value of their positions plummet, to such an extent that many received margin calls. Faced with margin calls, many funds began to sell their unlevered asset positions to provide extra money to avoid closing their open positions in financial derivatives. It seems, however, that many of the pension funds’ unleveraged positions were in UK government bonds, so there was a sell-off in the bond market that caused the price of these bonds to fall even further, generating new margin calls for other pension funds and other financial intermediaries in a full-blown financial panic. But even when the initial margin calls were not made, the creditor sold the position held by the pension funds to satisfy the debt and this sale caused the price of the financial derivatives to fall. This, in turn, generated new margin calls to other financial intermediaries. As can be seen, the system is unstable and fragile: once panic sets in, it is quite difficult to end it. The fragility did not originate in the market but is the result of regulatory intervention.

What we have explained is typical of financial contagion: leveraged positions are backed by the assets themselves, so a fall in the price of the asset—generated by margin calls—causes the asset itself to be sold. This cascade effect causes overselling to spread like wildfire.

How Will the UK Financial Panic End?

The panic ended when the Bank of England decided to buy a huge amount of bonds over the course of two weeks. This has calmed the oversold markets and prevented the panic from spreading to other assets, at least for now.

The problem is that the pound sterling has a fairly serious inflationary problem, which is being addressed by tightening monetary policy. But tight monetary policy involves asset sales by the central bank, not asset purchases. In other words, the Bank of England has decided to save UK pension funds at the cost of further increasing inflation in the UK. It is possible that more such panics will occur in both the UK and other developed economies that began fighting high inflation by tightening credit conditions in their respective countries.

The Bank of England’s bailout implies that the UK monetary authority is succumbing to financial pressures and is ceasing to fight inflation, so we might expect UK inflation to not moderate in the near future. The Bank of England has just saved part of the UK’s financial sector and pensioners at the expense of everyone who saves in pounds sterling and who will continue to see the currency’s value plummet, both in capital markets and in the markets for goods and services.

Legal notice: the analysis contained in this article is the exclusive work of its author, the assertions made are not necessarily shared nor are they the official position of the Francisco Marroquín University.

—

[1] In the UK, defined-benefit funds make up the majority of public sector–employee funds. However, the majority of private sector funds have shifted over the last twenty years to defined-contribution funds.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Daniel Fernández

Daniel Fernández is the founder of UFM Market Trends and professor of economics at the Francisco Marroquín University. He holds a PhD in Applied Economics at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid and was also a fellow at the Mises Institute. He holds a master in Austrian Economics the Rey Juan Carlos University and a master in Applied Economics from the University of Alcalá in Madrid.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions