Differentiated Minimum Wages: An Obsession?

By Clynton R. López F. February 11, 2016

Translated from Spanish by Katarina Hall

For some time now Guatemalans have vehemently discussed the idea of differential minimum wages as a measure to attract capital to regions where unemployment rates are higher. The debate seems to have lost its theoretical focus and turned into a political issue. In basic economic theory, differential minimum wages themselves are not addressed. Instead focus shifts on to the establishment of minimum wages that compromise the market’s ability to adjust to technological shocks, among other things.

Besides the so-called shocks, traditional basic economic theory addresses how a region’s salary levels depend on its level of capitalization. Most likely, this is where the theoretical focus is lost, shifting into a political discussion. A region’s level of capitalization does not directly depend on minimum wage levels. In other words, while it is true that differentiating wages help attract capital, relatively low minimum wages alone do not constitute all of the elements that allow a region to capitalize. The regions in Guatemala where differential minimum wages are being proposed are not poor by the current minimum wage level. The minimum wage in those regions can only help explain their poverty. A region’s poverty can be explained more broadly through other reasons, ranging from private decisions to collective decisions in politics.

The elements that explain the economic growth of a region can be found in the empirical studies of Barro (1996), among others, in which differential minimum wages are not the cause of this economic phenomenon. Instead, the region’s economic growth is explained by other factors, such as the levels of savings, government consumption, private property rights, judicial services, terms of trade, and economic freedom.

Does this mean that minimum wages do not affect poverty levels? No. Minimum wages considerably harm a region’s economic freedom. A differential minimum wage established around wealthy regions does relatively less harm. However, the importance of the issue remains: minimum wages hurt the economy, especially the least productive workers.

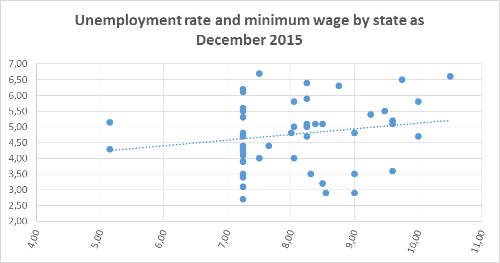

The graph shows the simple relationship between unemployment rates in each US state and their minimum wage level. The information (December 2015) subtly suggests that unemployment levels are greater in areas that have higher minimum wage requirements (regardless of each state’s capitalization per capita). Minimum wages hurt the very same people they seek to help, but by themselves they are not enough to explain a region’s wealth or poverty. Guatemala’s minimum wage discussion should not only seek to eliminate minimum wages, but it should also address how to improve capitalization levels by improving property rights and the justice system, as well as, for example, the population’s saving tradition. Otherwise, differential minimum wages will only continue to be a political issue.

To answer the initial question: differential minimum wages have become a political obsession, probably because of the country’s desperate poverty that affects millions of Guatemalans.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Clynton López

Clynton López is a professor at the Francisco Marroquín University since 2002 in the areas of economics and philosophy. He has a degree in Economics with a specialization in Finance from the Francisco Marroquín University and a master in Economics from the same university, both Magna Cum Laude. He studied executive programs at Boston University on Managerial Economics & Corporate Finance, the Master of Philosophy at the Rafael Landívar University (specialization in phenomenology), and the Post Graduate Degree in INCAE for Senior Management. In the professional field he has more than 10 years of management experience in banking and financial companies in Guatemala, California and Puerto Rico, and is a member of the Mont Pelerin Society.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions