This Is What Businesses Are Doing with Record Corporate Debt

Last year, non-financial companies issued $674.3 billion in corporate debt, a new record high. The previous record high was reached a year earlier, in 2015, with $670 billion in corporate debt issuance. However, company directors, whose primary task is to allocate capital, are increasingly allocating capital in a pernicious way. Low interest rates are wrecking the allocation of capital: the increase in debt is not used to invest, but rather to distribute cash to shareholders. There is, however, one important caveat to this whole scheme that will threaten the U.S. economy.

Businesses as Capital Allocators

In 1987, legendary investor Warren Buffett wrote to his investors that:

[T]he heads of many companies are not skilled in capital allocation. (…) The lack of skill that many CEOs have at capital allocation is no small matter: After ten years on the job, a CEO whose company annually retains earnings equal to 10% of net worth will have been responsible for the deployment of more than 60% of all the capital at work in the business.

Businesses allocate capital. Stock market investors look for boards of directors that allocate capital efficiently. Are they able to (re)invest in projects that return more than the cost of finance? Whenever a board is convinced that it cannot generate returns exceeding the cost of capital, it should return money to shareholders. One way to return money to shareholders is by buying back shares. With less outstanding shares, each share should be worth a little bit more than before. Another way is to pay out dividends.

Corporate Debt Is Creeping Up

What would you do as a business owner if your borrowing costs are near zero? The rational response is to borrow money at zero and reinvest it in, well, about anything. In other words, an efficient allocator of capital (that is, an efficient board) would borrow more, since the opportunity cost of adding debt is low.

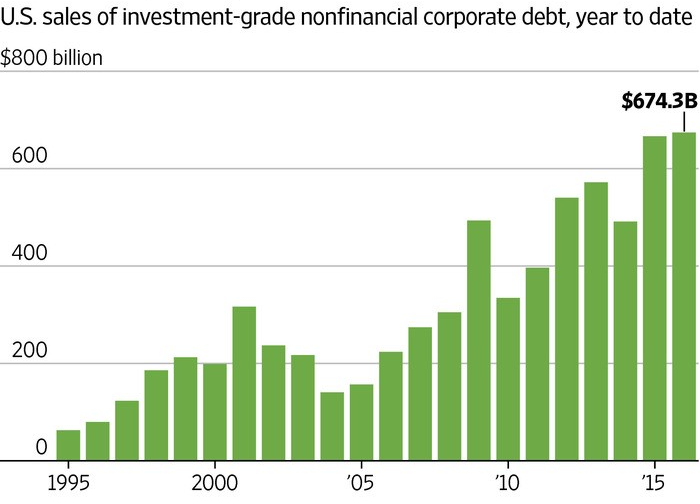

In the following chart, courtesy of the Wall Street Journal, we can observe that nonfinancial companies have done exactly that. Record corporate debt was issued in the past two years, which is a logical consequence of low interest rates.

Nevertheless, leverage is a function of two variables: debt as a share of the total balance sheet. Is there any equity – capital – to offset the rise in debt? We might assume that corporate earnings have been wonderful lately and companies have put flesh on their bones. Debt might have increased, but equity might have increased even more.

Yet this has not been the case. If we take a look at median corporate debt relative to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) we see an increase in leverage. Better yet, nonfinancial corporate leverage is greater than in 2008, when we suffered the Great Recession.

The Cost of Debt Is Rising Rapidly

Now, record low interest rates are not forever. While for some capital allocators the rational thing to do was to borrow and reinvest (in about anything), this rationale disappears rather quickly when the cost of borrowing rises.

And that is exactly what is happening.

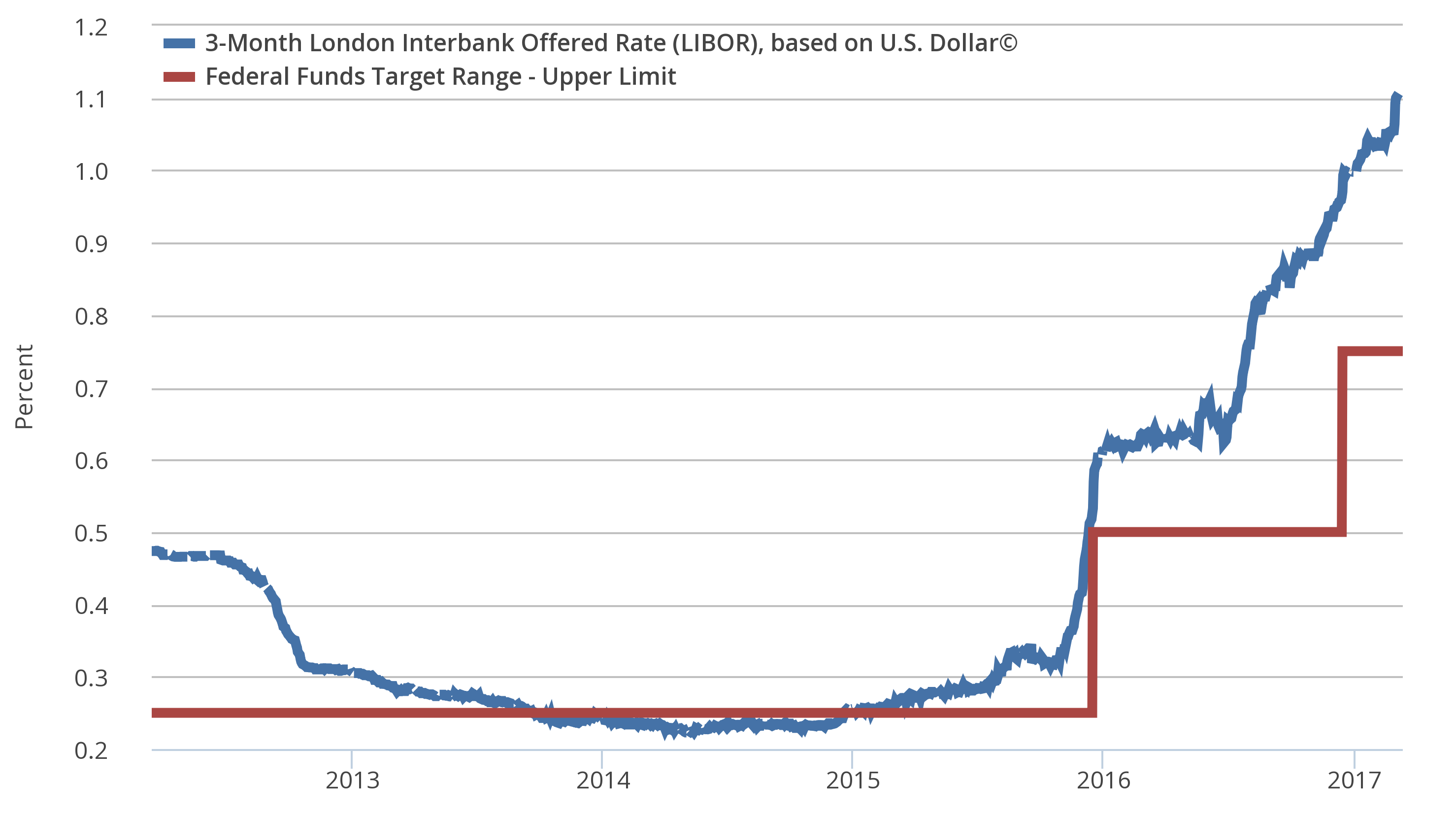

Look, for instance, what has happened with the most important interest benchmark in the world, LIBOR:

The red line is the upper ceiling of the target Fed funds rate; the blue line is the 3-month US dollar LIBOR. LIBOR interest rates are often used in all sorts of credit agreements. The nominal interest rate of a credit is then fixed at LIBOR + a premium. In other words, a rise in LIBOR has a direct effect on the borrowing costs of a wide range of borrowers.

In effect, borrowing costs have quadrupled since 2015. The idea that this will have no repercussion on corporate balance sheets is ludicrous.

What Are Businesses Doing with That Debt?

As we have seen, corporate management is to be judged according to its ability to allocate capital rationally. With record low interest rates, debt issuance and corporate leverage have (as expected) been rising.

What are businesses exactly doing with that debt? The unnerving answer is: share buyback programs.

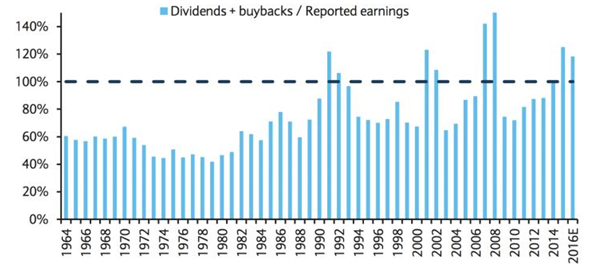

Whenever a company thinks it cannot reinvest capital profitably, capital should be redistributed to shareholders. One way to redistribute capital is, as we have explained, by buying back shares in the open market. Another way is to pay out dividends. If we add up both, we get something we call the total payout ratio.

Corporate buyback programs have been ubiquitous. Last year, share repurchases reached a post-Great Recession high with over $160 billion in share repurchases by S&P 500 companies (source: Factset’s BuyBack Quarterly, Dec 2016).

Last quarter, 119 companies in the S&P 500 spent more on buybacks in the trailing twelve months ending in Q3 than they generated in earnings. The total payout ratio (gross buybacks and dividends) equaled 117% of earnings in the last quarter and was higher than 100% during the entire past year. In other words, businesses are paying out more in dividends and buybacks than their reported earnings. That would be akin to paying more in taxes than what you earn in wages.

(Source: S&P, Haver, Barclays Research)

(Source: S&P, Haver, Barclays Research)

Are we seeing a shift? Perhaps. Buybacks plans have reached four-year lows. We might wonder when this shift will translate into lower stock market prices.

The overall conclusion is frightening: businesses are taking on increasing levels of leverage, the increase in debt is not reinvested in the business but distributed to shareholders, and at the moment businesses distribute more to shareholders than what they actually earn. The last two times that this has happened was in 2008 and 2001, and in both occasions we were in the midst of a recession. Perhaps our outlook should be gloomier if we take into account that a great deal of the U.S. economic recovery is based on increasing leverage with borrowing costs bound to rise.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Olav Dirkmaat

Olav Dirkmaat is professor in economics at the Business School of Universidad Francisco Marroquín. Before, he was VP at Nxchange and precious metals analyst at GoldRepublic. He has a PhD in Economics from the King Juan Carlos University in Madrid. He has a master in Austrian Economics from the same university, as well as a master in Marketing Strategy from the VU University in Amsterdam. He is also the translator of Human Action of Ludwig von Mises into Dutch. He has a passion for investing, and manages funds for relatives, looking for investment opportunities in markets that are extremely over- or undervalued.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions