Business Cycles, Commodities and Equity Investment

By Clynton R. López April 25, 2016

Translated from Spanish by Robert Goss

After 2008, commodity-producing countries experienced an economic boom that resulted in an ever-growing and sustained rise in prices. These price increases were unprecedented when analyzing the history of such commodities.

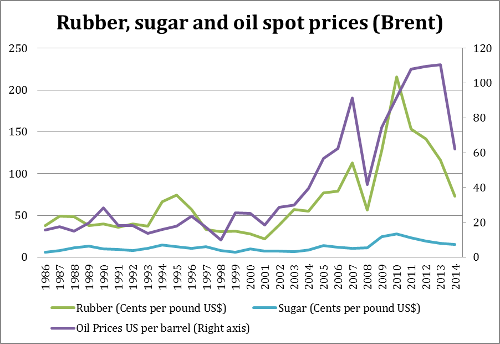

Graph 1

In graph 1, it can be noted that both oil and rubber saw prices that hadn’t been seen in 30 years. Sugar also saw an increase in price but at a much more moderate rate. Is it reasonable to assume that during a time when global economies began an intense economic cycle, the prices of these commodities saw an increase of such proportions?

The answer, without being completely conclusive, is most likely found when analyzing the pro and countercyclical variables. Procyclical variables are those that are positively correlated with the business cycle whereas countercyclical variables are negatively correlated.

There are many explanations regarding this phenomenon. Recently, one of the most popular explanations has been the theory of maturity mismatches brought on by financial intermediaries. In this theory, financial intermediaries attempting to intervene on the interest rate curve, mismatch their balance sheet by possessing more long-term capital assets and less assets considered working capital. By doing so, a scarcity of commodities eventually arises and coincidentally occurs at the beginning of the business cycle. In order to survive, equity investments then compete for the necessary commodities in order to function properly.

Although this interpretation could be a plausible one for certain commodities, it is unlikely for many industrial commodities. Perhaps the most important contribution we can take from the theory derived by the Austrian School of Economics – at least in this case – is the division of time taken for production processes. This point can be exemplified with the examination of just two commodities. The production process of rubber can be understood in two forms: as an industrial process that processes the sap from the tree (in this case the natural rubber obtained directly from the rubber tree) and sold as a latex or rubber derivative (SMR20 or RSS3 to mention a couple). Setting up this process can be relatively short. Financing the extraction of the sap can be considered a social circulating capital, just as per Adam Smith.

The other way that this process can be analyzed, without losing sight of the fact that if it is the case that the extraction of rubber as a commodity can be seen as a social circulating capital, is recognizing that establishing a rubber tree plantation is a production process of at least 5 to 7 years depending on the type of tree used. This, according to the maturity mismatch theory, would be an example of the possession of more long-term assets when intervention occurs in the interest rate curve. Because of this, its price should not be seen as a countercyclical variable but rather cyclical with delay.

The other commodity to be used as an example is oil. When a new oil field is discovered and being worked, there may be short-term financing, which could be considered, in a sense, social circulating capital. The time period for financing oil exploration is quite different and it would be difficult to consider this a social circulating capital.

This last interpretation makes it even more plausible that the classic theory describing the rise in these prices – and in turn earnings greater than 0 – generates revenue from new competitors that increase supply (as Knight would say, the longer-term the investment, the higher the uncertainty). Because of the delay in the production process, the demand conditions could see a change, and the price affected by supply and the decrease in demand could continue downward.

This is to say that upon review of the business cycle theory of Thomas Tooke, it is quite revealing. Credit itself, or the availability of credit, with or without the existence of maturity mismatching, does not create the business cycle. There must previously exist some speculative talk about the prices of certain goods that, combined the availability of credit, can generate an over-production of said commodity.

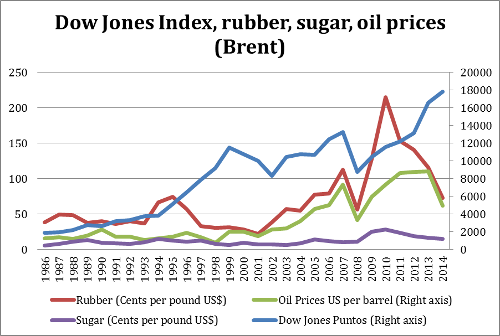

Graph 2

In Graph 2, we see the same data as in Graph 1 but with the Dow Jones Index added. A clear correlation can be seen between the Dow Jones and the commodities, at least since 2010. These commodities are currently being affected by demand in the market. Any commodity player knows that investment funds work on earnings on financial investments dealing with commodity futures contracts (short or long term). This produces fluctuations in prices (Tooke-style speculations), and here the availability of credit does play an important role. A monetary surplus most likely provided a fantastical sense of security to the trading sector which, during its collapse, sought a safe haven in commodities. This safe haven most likely generated overproduction that is still felt today with some of the lowest prices seen in some time, and others where prices continue to drop.

The global economy is quite complex (many players, in many different places, and complex production processes of many different lengths of time) and unprecedented monetary distortions have created distortions in all markets that are still being felt to this day.

Revisiting old theories with new events is an interesting way of using accumulated knowledge in economic and financial processes, but it requires the important ability of understanding and distinguishing contemporary times. The maturity mismatch theory, explained from the perspective of commodities, hardly seems plausible. The use of basic and classic theories or those of Thomas Tooke seem to explain the countercyclical behavior of commodities in a better way.

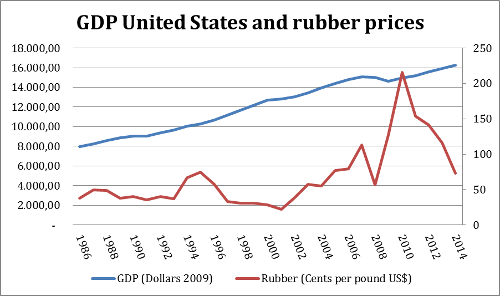

Graph 3

In Graph 3 we can see the relationship between the real GDP of USA and the price of rubber, but, upon carrying out a simple regression between the increase in the price of rubber as the dependent variable and economic growth of the US as the independent variable, we can see valid statistical results after 18 months. The result is that it is effectively a countercyclical variable after a delay of at least 18 months. At least, this would be the understanding based on the basics of econometrics.

Lastly, there exist some open-ended questions. Can one understand the business cycle based on commodities? Does the theory that there exists a cycle of liquidity crises by means of maturity mismatches explain the countercyclical mannerisms of some commodities? Are Tooke’s and other classic theories more plausible when explaining countercyclical mannerisms due to delays in production? Maybe the most plausible conclusion is that commodity producers are anxiously awaiting a drop in the stock market in order to see an increase in their prices. Or perhaps the price of commodities is a variable with just another random path…

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions

Clynton López

Clynton López is a professor at the Francisco Marroquín University since 2002 in the areas of economics and philosophy. He has a degree in Economics with a specialization in Finance from the Francisco Marroquín University and a master in Economics from the same university, both Magna Cum Laude. He studied executive programs at Boston University on Managerial Economics & Corporate Finance, the Master of Philosophy at the Rafael Landívar University (specialization in phenomenology), and the Post Graduate Degree in INCAE for Senior Management. In the professional field he has more than 10 years of management experience in banking and financial companies in Guatemala, California and Puerto Rico, and is a member of the Mont Pelerin Society.

Get our free exclusive report on our unique methodology to predict recessions